The following post was authored by Digital Archivist Paul Kelly.

The Archives has several different media types in its holdings, and some of these, such as magnetic tape, are much more susceptible to degradation than paper. Audio cassettes and open reel tape can, over time, become sticky and difficult to play without causing irreparable damage, if stored in less than perfect conditions. They can also suffer data loss when exposed to magnetic fields (this can happen just by storing cassettes close to high-powered speakers), and digital media can suffer data rot. CUA Archives decided to get ahead of the game here; since our audio materials are still in good condition, why not duplicate them for preservation and access while we still can?

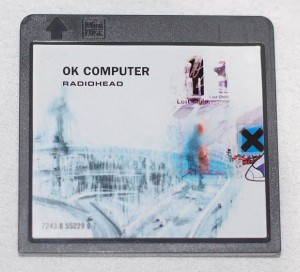

Remember that technology graveyard I mentioned in my digital curation blog? Well, it contains more than just computer equipment. Think cassette decks, reel to reel players, turntables, and, yes, even minidisc and DAT players.

Any analog audio device with an RCA-out can be connected to a computer via USB. While we use a Behringer U-PHONO to get this done, other options are out there. For the digital stuff, we currently use TOSLINK, but have plans for future direct data capture, as demonstrated in the Fugazi Live Series project (if you happen to have a Sony SDT-9000 gathering dust in your basement, let me know).

So we’ve connected our player to the PC – now what? The short answer is we use Audacity to capture audio and BWF MetaEdit to create metadata. The longer version is that there are several exciting steps between recording and having an audio file ready to go. Try to stay awake here. First of all, we need to set an appropriate recording level – too high, and the sound is distorted; too low, and it’s inaudible (note: this is not necessary for bit to bit capture). Once we hit that non-brickwalled sweet spot, we can press play on the source, and hit record in Audacity. When recording is complete, we create two files – one for access (192 kbps, 44.1 kHz MP3), and one for preservation (24 bit, 96 kHz WAVE).

Done? Not exactly. While the MP3 is exactly what we want, there’s one last thing we need to do to the WAVE before shuffling it off into preservation storage. Some background: the WAVE format is extensible, meaning that we can add additional layers to the file. BWF MetaEdit allows us to attach extra metadata to the digital audio, retaining the core of the WAVE but saving it as a Broadcast WAVE (or BWF), which is exactly what we need. Once this step is complete, we’re finished!

The best thing about these software packages is that anybody can use them – they’re free, and open source. If you have this equipment at home (…or at mom and dad’s place) there’s literally nothing stopping you from ripping those old tapes and LPs instead of paying through the nose for reissues of dubious utility on Record Store Day. I promise you’ll feel better for it. Have fun experimenting, folks.