When those familiar with The Catholic University of America think of this school, they may think of a national Catholic University, which it is. It also served as the center of Catholic education in the United States throughout the first half of the twentieth century.

Back in the late-nineteenth century, a man named Thomas J. Conaty served as the Rector of CUA. Conaty established what would become the framework of the American Catholic school system during his years as rector, 1896-1903. He convened the first meeting of the Conference of Seminary Faculties and became the founding president of both the Association of Catholic Colleges and the Parish School Conference. It was Conaty’s vision to create a national organization that would embrace all levels of Catholic education. As fate would have it, he was promoted to Bishop of Monterey-Los Angeles before he could complete his plan.

At that point, Ohio-born Francis Howard grabbed the reigns of the fledgling organization from Bishop Conaty and ran with them. Howard forged it into the Catholic Education Association (“National” was added to the title in 1927), and became its first secretary, serving for 25 years. He managed the organization out of offices in Columbus Ohio until he became Bishop of Covington, Kentucky in 1923. Howard was also drafted to run the new National Catholic Welfare Conference’s Department of Education in 1919; he declined, but agreed to serve on the executive committee. If you are wondering why both a National Catholic Education Association and an NCWC Education Department were necessary, consider the following: the early twentieth century saw several attempts to eliminate Catholic parochial schools through legal means by anti-Catholic forces in the U.S. Catholics in education needed someone to advocate for them. The Education Department, which was a bishop-run organization and therefore had the backing of the church’s highest authorities, was behind much of the effort to prevent the abolition of parochial schools. Though, like the NCEA, the Education Department conducted surveys and promoted Catholic education, its early years in particular were centered on monitoring legislation that affected Catholic schools.

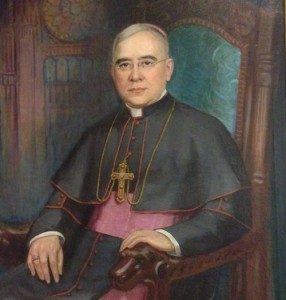

In any case, after 1920 the leaders of the CEA, NCWC Education Department, and Catholic University were intermeshed. Howard did not want the association with the University, preferring to keep its autonomy. Not so with his successor, George Johnson, who also happened to chair the Catholic University Department of Education. Johnson took over the helm of the NCEA in 1929, serving until his death in 1944. Johnson oversaw the movement of the entire educational operation to Washington, D.C. as well as its adaptation to modern administrative and professional standards.

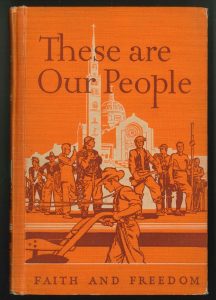

Democracy was popular topic in the 1930s, as it seemed under siege due to competing ideologies of communism and fascism. Catholic University was asked by Pope Pius XI to oversee a project creating a course of study of democracy through the Catholic educational system. Monsignor Johnson was asked to head the project. The resulting Commission on American Citizenship quite literally transformed American Catholic education, through a series of textbooks that would dominate American Catholic school civic education from the 1940s through the 1970s.

Johnson’s educational activities rippled outside of Catholic circles. He served as a member of the National Advisory Committee on Education appointed by President Hoover in 1929, and later on the Advisory Committee on Education appointed by President Roosevelt. He was a member of the Wartime Commission of the U.S. Office of Education, the Education Advisory Committee under the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs, Secretary of the American Council on Education. This list is not exhaustive–poor Monsignor Johnson must have been though. As he delivered the commencement address to the Trinity College class of 1944, he died at the age of 55. Adding further pathos to his demise while delivering the commencement speech, Johnson actually spoke the following lines: “the best, the truest, the most substantial advice that can be given to a Catholic graduate is this: Go forth and die. Die to yourself; die to the world; die to greed; die to calculating ambition… Die and you shall live, and live abundantly.”¹

The NCEA was in good hands with Johnson’s successor, Frederick Hochwalt, a topic for another post. Here is Johnson’s 1944 commencement speech and a short biography.

Sources:

Donald C. Horrigan, The Shaping of NCEA (Washington, D.C., n.d.).

John Augenstein, Christopher Kauffman, Robert Wister, One Hundred Years of Catholic Education: Historical Essays in Honor of the Centennial of the National Catholic Educational Association (Washington, D.C.: NCEA)

1 George Johnson, Apostle of Christian Education (Washington, D.C.: National Catholic Welfare Conference, 1944), 5, ACUA reference file, George Johnson.

Reading material like this has always been difficult for me, I love this article.