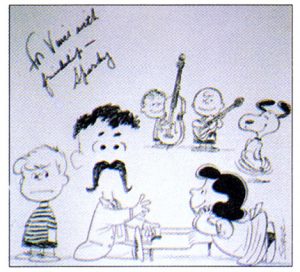

Picture it: San Francisco, late 1964. A young television producer, Lee Mendelson, has just finished filming a documentary on the popular comic strip Peanuts and its creator, Charles Schulz. Mendelson, a fan of jazz, needs a soundtrack for his documentary. He has already been turned down by the legendary Dave Brubek, as well as Brubek’s suggestion, vibraphonist Cal Tjader. He takes a cab ride, and as the taxi crosses the Golden Gate Bridge, a fresh new tune comes across the radio. It’s Vince Guaraldi’s “Cast Your Fate to the Wind,” and Mendelson knows immediately that he’s found the sound he needs. He schedules lunch with the pianist, who is eager to join the project. Two weeks later, Guaraldi calls Mendelson to play him a draft of what would become the theme of the strip, “Linus and Lucy.”¹

Unfortunately, Mendelson couldn’t get a network to pick up the documentary. What he got instead was an offer from the McCann Erickson advertising agency in New York. Following the success of General Electric’s special Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, McCann Erickson’s client, the Coca-Cola Company, wanted an animated Christmas special of their own, and they had their eyes on Schulz’s beloved Peanuts. Mendelson got Schulz on board, as well as director and animator Bill Melendez, and in less than a week had a basic storyboard completed. From the start, a central part to the special would be a soundtrack of jazz and traditional holiday music provided by Guaraldi. Coca-Cola loved the pitch, and A Charlie Brown Christmas went into production. The creative team had less than six months to finish the project.

For the score, Guaraldi provided jazz arrangements of “O Tannenbaum,” “What Child is This,” and Mel Torme’s “The Christmas Song.” He reused “Linus and Lucy,” which he had written for the unaired documentary, and provided other new tunes including the brisk waltz “Skating,” the energetically anticipatory “Christmas Is Coming,” and the melancholy yet enchanting “Christmas Time Is Here.” The recordings were made in the fall of 1965, just weeks before the special was due to air. A children’s choir from St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in San Rafael, California, was used to record “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing.” Mendelson and Melendez also wanted to add vocals to Guaraldi’s “Christmas Time Is Here” for the children to sing, but had trouble finding a lyricist. Mendelson took the job upon himself, and on the back of an envelope, he wrote a poem to fit Guaraldi’s simple melody:

For the score, Guaraldi provided jazz arrangements of “O Tannenbaum,” “What Child is This,” and Mel Torme’s “The Christmas Song.” He reused “Linus and Lucy,” which he had written for the unaired documentary, and provided other new tunes including the brisk waltz “Skating,” the energetically anticipatory “Christmas Is Coming,” and the melancholy yet enchanting “Christmas Time Is Here.” The recordings were made in the fall of 1965, just weeks before the special was due to air. A children’s choir from St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in San Rafael, California, was used to record “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing.” Mendelson and Melendez also wanted to add vocals to Guaraldi’s “Christmas Time Is Here” for the children to sing, but had trouble finding a lyricist. Mendelson took the job upon himself, and on the back of an envelope, he wrote a poem to fit Guaraldi’s simple melody:

Christmas time is here

Happiness and cheer

Fun for all that children call

Their favorite time of the year

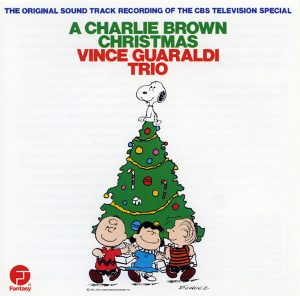

When the special was finished, just ten days before it was due to air, the creative team was worried they had failed. The juxtaposition of simple animations, contemporary jazz, and the recitation of Luke 2: 8-14 in the climactic scene by Charlie Brown’s best friend Linus made Mendelson nervous the network would reject it. Indeed, CBS executives were skeptical. However, the special had already been advertised, and the broadcast proceeded as planned. A Charlie Brown Christmas premiered on Thursday, December 9, 1965. Fantasy Records released the soundtrack that same month.

To the creators’ and network’s surprise, the reviews were unanimously positive. Richard Burgheim of Time praised A Charlie Brown Christmas for being “a special that is really special” with a “refreshingly low-key tone.”² Lawrence Laurent of The Washington Post lauded Guaraldi “who composed and conducted a delightful score.”³ The following May, the special won the Emmy for Outstanding Children’s Program. Just this past Friday, Billboard reported that the soundtrack to the special is back in the Top 40 for the third holiday season in a row at #32. They go on to note that it is the “seventh-biggest-selling Christmas album of the Nielsen era (1991-present), with 3.7 million copies sold.”⁴ In 2012, the Library of Congress added the album to the National Recording Registry to be “preserved as [a] cultural, artistic and/or historical treasure[] for generations to come.”⁵

A holiday song to be treasured by generations? That’s what the American Christmas songbook is all about, Charlie Brown!

¹https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/deck-the-halls-with-vince-guaraldi

²Burgheim, Richard, “Security Is a Good Show,” Time, December 19, 1965, p. 95.

³Laurent, Lawrence, “Loser in ‘Peanuts’ Finally a Winner,” The Washington Post, December 11, 1965.

⁵https://www.loc.gov/item/prn-12-107/new-entries-to-the-national-recording-registry-2/2012-05-23/

Since then, “This Christmas” has been covered over 100 times! If only Hathaway had lived to see his song become such a standard–he passed away at age 33 in 1979. Phil Upchurch, guitarist and friend of the late Hathaway, said of the work: “‘This Christmas’ is absolutely the premiere holiday song written by an African American.”³

Since then, “This Christmas” has been covered over 100 times! If only Hathaway had lived to see his song become such a standard–he passed away at age 33 in 1979. Phil Upchurch, guitarist and friend of the late Hathaway, said of the work: “‘This Christmas’ is absolutely the premiere holiday song written by an African American.”³

Before Neptune’s Daughter premiered, Dinah Shore and Buddy Clark had

Before Neptune’s Daughter premiered, Dinah Shore and Buddy Clark had

“I’ll Be Home for Christmas” has been recorded by countless artists since Bing Crosby. Perry Como

“I’ll Be Home for Christmas” has been recorded by countless artists since Bing Crosby. Perry Como

And for most early commercial recordings, that is the name that appears on the label. The

And for most early commercial recordings, that is the name that appears on the label. The

In the summer of 1950, Paramount Pictures approached Jay Livingston and Ray Evans, a songwriting duo with a knack for writing hit numbers for films and theme songs for television series (Bonanza and Mr. Ed). Paramount was working on the film The Lemon Drop Kid, which is set in New York City in the days leading up to Christmas. Thus, the studio felt the picture needed a Christmas song, and they wanted it to be sung by the leads Bob Hope and Marilyn Maxwell. Initially, Livingston and Evans were less than enthusiastic. In a 2005 interview recorded for NPR, Evans recalled: “…[w]e figured–stupidly, thank God–that the world had too many Christmas Songs already.”¹ They were also nervous that another flop would result in Paramount terminating their contract, which was up for renewal.

In the summer of 1950, Paramount Pictures approached Jay Livingston and Ray Evans, a songwriting duo with a knack for writing hit numbers for films and theme songs for television series (Bonanza and Mr. Ed). Paramount was working on the film The Lemon Drop Kid, which is set in New York City in the days leading up to Christmas. Thus, the studio felt the picture needed a Christmas song, and they wanted it to be sung by the leads Bob Hope and Marilyn Maxwell. Initially, Livingston and Evans were less than enthusiastic. In a 2005 interview recorded for NPR, Evans recalled: “…[w]e figured–stupidly, thank God–that the world had too many Christmas Songs already.”¹ They were also nervous that another flop would result in Paramount terminating their contract, which was up for renewal.

Following the release of The Christmas Mood, “Some Children See Him” was

Following the release of The Christmas Mood, “Some Children See Him” was