The mixed legacy of heroic sacrifice and bitter division of the American Civil War continues to permeate popular culture and political discourse. As a growing minority in the 1860s, making up about ten percent of the United States population concentrated in the north, Catholics were embedded in this conflict. Their relatively unknown story was recently and expertly addressed by historian William B. Kurtz in his book Excommunicated from the Union: How the Civil War Created a Separate Catholic America. As Kurtz relates, amidst fears Catholicism was incompatible with republican government, the Civil War gave Catholics a chance to prove their loyalty, with nearly 200,000 serving as Union soldiers, fifty-three priests as chaplains, and over six hundred nuns engaged as nurses. Unlike later wars, especially World War I, there was no national coordination by the hierarchy, though many bishops were supportive, as were many in the Catholic press. In Rome, Pope Pius IX was neutral, considering the war a minor affair. A 2015 post from The Archivist’s Nook related the war’s influence on the grounds of what became The Catholic University of America while this post examines the war more broadly, using archival holdings and museum artifacts from Catholic U’s Archives.

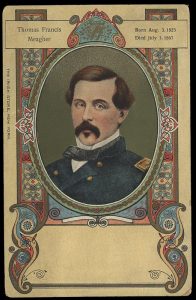

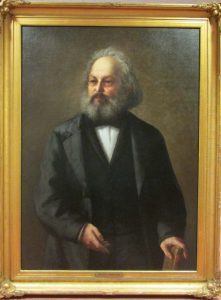

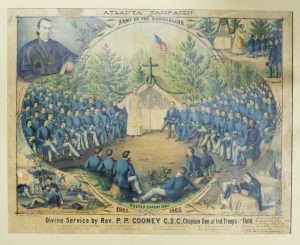

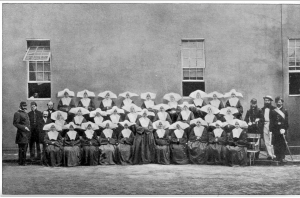

Antebellum anti-Catholicism and the question of Catholic patriotism during the Mexican War was a rehearsal for similar debate during the Civil War. Following the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 and resulting secession of southern states, many notable Catholics, such as New England publisher Orestes Brownson and Archbishop John Hughes of New York, strongly supported the Union, as did most Catholic men. Catholic civilians took pride in symbols of their patriotism from the celebrated Irish Brigade to notable high-ranking generals William S. Rosecrans and Philip H. Sheridan. Battlefield interaction and the comradeship of soldiers often weakened religious prejudice as did the service of chaplains and nurses. Notable chaplains included future Minnesota archbishop John Ireland, Notre Dame alum Peter Cooney, and William Corby, who famously gave absolution to Union troops at Gettysburg on July 2, 1863. Nuns, serving as nurses, were largely from the Sisters of Charity, but also Sisters of the Holy Cross, such as Mother Angela Gillespie, a cousin of William T. Sherman whose wife was also Catholic.

However, like most other Democrats, Catholics tired of the war’s bloody toll by 1863 as many resisted emancipation, suspension of civil liberties, and the military draft. While many northern Catholics disliked slavery, they were reluctant to support Republican abolitionists who were often hostile to Catholicism, and there were fears after Republicans eliminated slavery they would next attack Catholics. Notably, Archbishops Hughes of New York and John B. Purcell of Cincinnati, respectively, as well as General Rosecrans supported emancipation while Paulist priests Isaac Hecker and Augustine Hewett bravely confronted Irish-Catholics rioting in New York City against the draft in 1863. In the 1864 presidential election, Catholics tended to support General George B. McClellan rather than Lincoln, though the latter’s victory in the polls, as well as military victory in the field by armies that still included thousands of Catholics, many of them Irish and German immigrants, successfully concluded the war. Unfortunately, Lincoln’s tragic assassination complicated matters as many of the conspirators were Catholics, including Mary Surratt, the first woman to be executed by the federal government.

After the war, anti-Catholicism remained strong as additional immigrants from southern and eastern Europe settled in ethnic neighborhoods thus furthering isolating Catholics from mainstream America. Catholic apologists publicized their wartime sacrifices celebrating chaplains and the Irish Brigade while ignoring slavery and the draft riots. Despite his defeat at Chickamauga, Rosecrans rather than the less pious and far more successful Sheridan became the greatest Catholic Civil War hero as the most prominent devout Union officer and Catholic Civil War memory largely became an Irish memory with non-Irish, especially German Catholics, overlooked. Catholics would find new opportunities to demonstrate their loyalty in two world wars. In 1917 the bishops created the National Catholic War Council to present a united front and patriotic image in World War I. Despite a resurgence in the 1920s, Anti- Catholicism declined thereafter because of the Church’s unequivocal patriotic response to World War II. By the twenty-first century, overt prejudice was no longer a pressing issue and Catholic Americans honor their ancestors without the need to prove their faith’s compatibility with modern American society.

One could conclude from this essay that, aside from Mary Surratt and a few unnamed conspirators, there were no Roman Catholics in the South.

I’m also agreed with Nicholas. Thanks for sharing