Primary vs. Secondary Sources

Perhaps one of the best ways is to examine documents from an era or event of interest; these are known as primary sources. The Library of Congress defines it as “Primary sources are the raw materials of history — original documents which were created at the time under study. They are different from secondary sources, accounts, or interpretations of events created by someone without firsthand experience.” These sources can be almost anything; a document, artifact, oral history, postcard, etc. Secondary sources, on the other hand, are generally books or articles written about a primary source or document. They contextualize and interpret the primary source in question. [1]

Finding primary sources can be difficult depending on the topic. But, the best places to start are online collections from libraries, museums, and archives, all memory institutions that rely on such documents for their collection and viewing. Today, these institutions are pushing to digitize documents and artifacts to make them accessible to patrons from anywhere in the world. For me, I am currently pursuing a double master’s in History and Library Science. The ability to access digitized documents allows me to engage with the past and apply it to my research. While I cannot physically hold, touch, or feel the document I am studying, through digitization, I can engage with a virtual reproduction or scanned image of the source. Primary sources are essential to my career path and working with them either hands on in the archives or scrolling through scans in a digital collection allows me to engage with topics of interest.

Transcribing

How can you gain more experience interacting with primary source documents? Several institutions, large and small now offer crowdsourcing opportunities to transcribe documents within their collection. More sophisticated programs include the Smithsonian Institution and the National Archives, but more localized libraries and museums also participate. To gain a sense of the process for transcribing documents, I chose the Smithsonian Institutions because this includes all museums as well as their respective library and archives. After you create an account, then you can choose a specific museum or theme of interest. I picked African American History, Women’s History, and the Archives of American Art so I could have a range of themes and experiences.

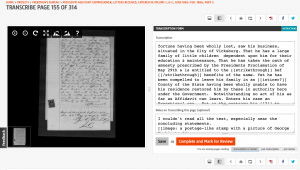

Before beginning, a tutorial is suggested for viewing. In the tutorial, guidelines for transcribing and notating are covered. There are different roles you can take on for these projects. The obvious one being transcribing, typing up what the document says verbatim. The other option is to review and edit what another volunteer transcribed. A general rule for all transcription sites is a three step process: a volunteer transcribes the document, a different volunteer reviews, and then the document is submitted for an employee of the institution to provide a final review before providing online access.

My Experience

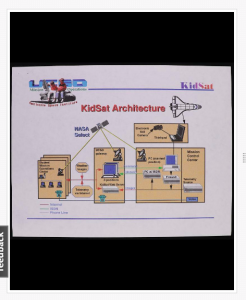

Sally Ride Papers: The first collection I worked on was the Sally K. Ride Papers housed at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum Archives. The Sally Ride Papers contain reports, speeches, photographs, etc. I personally worked on documents related to the KidSat program. Sally Ride created this program along with other scientists as a way for school-aged children to look at images of Earth using a camera aboard a Space Shuttle.

These documents were print documents, so reading handwriting was not an issue. Although, with print documents the question of how to arrange graphs, charts, and caption boxes becomes tricky. Luckily, the Smithsonian provides a tutorial on documenting these irregular texts. For this collection, I also reviewed some transcriptions of other volunteers. This was also a good opportunity to see how others handled describing the graphs and images within the text.

Freedmans’ Bureau: The Freedmens’ Bureau was a government organized agency created during the Reconstruction era to help integrate freed slaves into society. The success of the agency is contested by historians, but the Bureau did set high standards for black education. Under President Lincoln’s administration in 1865, the agency formed as a sect of the Department of War. Most the documents within the transcription collection deal with labor contracts between freedmen and local superintendents. The collection is archived at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. [2]

Experience: This collection proved a bit more difficult than the Sally Ride Papers in that most documents were handwritten and from the late 1800s. Deciphering the handwriting from the time period was challenging at time, but after looking at a few documents, one can begin to see the continuities in certain words and letters. The subject matter for these documents proved to be a bit mundane, as they were mostly contract, but nonetheless it was fascinating reading materials over 100 years old!

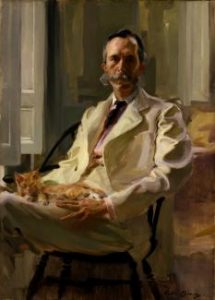

Lastly, I worked on transcribing documents from the “Letters From Paris: American Artists in Paris, 1860-1930.” This project contained letters from various American artists while they lived or visited Paris. Specifically, for me, I chose Cecilia Beaux’s correspondence from 1888. Beaux was a portraitist during the Impressionist movement. Some of her works include “Man with the Cat,” and “Admiral Sir David Beatty, Lord Beatty.” [3]

Like the Freedmen’s Bureau papers, these were also difficult to read due to the handwriting of the time. Her letters mostly relayed the daily activities of her time in France; visiting friends, going to church, etc. While I was not quite familiar with Beaux or her personal life, I found the personal correspondence to be more interesting rather than the government documents of the Freedmen’s Bureau or Sally Ride Papers.

I greatly enjoyed the experience transcribing pieces of the past! I recently took a history course on the 19th century in which we learned about the Reconstruction era and the Freedmen’s Bureau. I was able to apply what I learned in class and contextualize the document I transcribed from the organization. In the moment, it may seem difficult to decipher a word or understand the meaning of the document, but once a letter is completely transcribed a feeling of accomplishment takes over.

How you can get involved

There are numerous crowdsourcing opportunities for you to transcribe! Here in Washington, D.C. three of the largest institutions offer digital volunteer opportunities: Smithsonian Institution (you can pick a museum or theme of interest), the National Archives, and the Library of Congress. Smaller institutions occasionally host events such as a “Transcribe-a-thon” for certain collections. Not only is this a great way to help out, but it provides experience examining primary sources and you just might find a source you want to learn more about or use in your own research!

The Smithsonian: https://transcription.si.edu/

Library of Congress: https://crowd.loc.gov/

Library of Virginia: http://www.virginiamemory.com/transcribe/

National Archives: https://www.archives.gov/citizen-archivist

References:

[1] “Using Primary Sources.” The Library of Congress. http://www.loc.gov/teachers/usingprimarysources/

[2] “Labor Contracts.” Smithsonian Institution. https://collections.si.edu/search/record/ead_component:sova-nmaahc-fb-m1902-ref103, “Freedmen’s Bureau.” https://transcription.si.edu/browse?filter=owner:16

[3] “Cecilia Beaux.” Smithsonian American Art Museum. https://americanart.si.edu/artist/cecilia-beaux-300