Our guest blogger is Meghan Glasbrenner, who is a student worker at the University Archives and a graduate student in Library and Information Science (LIS) at the Catholic University of America.

As part of my coursework I was given the opportunity, in place of a traditional final research paper, to formally arrange and process the Janaan Manternach and Carl J. Pfeifer Papers, which had been acquired by the CUA Archives from 2020 through early 2021. I am thrilled to share that the collection, which spans some 70 years, now has an online finding aid.

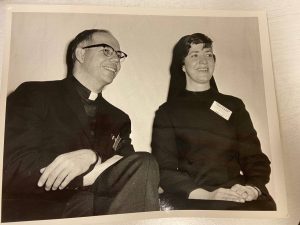

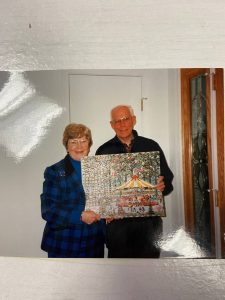

As was discussed in an earlier Archivist’s Nook post by guest author Tricia Campell Bailey, the collection includes a mix of both personal and professional items and documents, with the former focusing on the couple’s personal lives and relationships, both individually and jointly, including their choices to be released from their religious vows after they developed a call to marry in 1976. However, the largest portion of the collection can be found in its extensive holdings related to their professional activities, most notably their groundbreaking work in revising formal religious education’s use of the Baltimore Catechism, focusing instead on making the lessons, morals, and foundations of the Catholic faith accessible and relatable for everyone.

The Baltimore Catechism’s question and answer format (of which the standard edition has 421 and the abridged edition 208) is familiar to anyone who grew up attending Catholic school or CCD classes through the 1960s, as it was in effect the text for US Catholic instruction as far back as 1885. Traditional instruction using this text involved students memorizing and repeating a series of questions and their provided responses, which ranged from simple statements such as #6: “Q. Why did God make you? A. God made me to know Him, to love Him, and to serve Him in this world, and to be happy with Him forever in the next” through more complex concepts such as #339 “Q. What benefits are derived from the communion of saints? A. The following benefits are derived from the communion of saints:—the faithful on earth assist one another by their prayers and good works, and they are aided by the intercession of the saints in heaven, while both the saints in heaven and the faithful on earth help the souls in purgatory”.

While the Baltimore Catechism provided an extremely detailed breakdown of the core teachings and beliefs of the Catholic faith, what religious education teachers, such as Sister Janaan and Father Pfeifer, discovered during their instruction was that while their young students may have been able to successfully repeat these memorized phrases, they weren’t demonstrating a real understanding or connection. Taking a chance, Sister Janaan began quietly experimenting with new teaching approaches, most notably incorporating art, poetry, and music into her lessons, such as using religious-themed paintings to help children visualize abstract mysteries and pillars of the faith and short, simple songs and poetry writing exercises to give them space to voice their own understandings and questions. In a draft of the introduction to her 1982 collaboration with Carol Dick entitled The Gift of Me: Songs for Children (a copy of which is available in the collection), Manternach sums up this belief when she states, “Songs have a power that no other medium has for freeing children into meaning and feeling. Songs sung have the power to unite, to teach, to heal, to relax and to make events into celebrations and/or solemn occasions.”

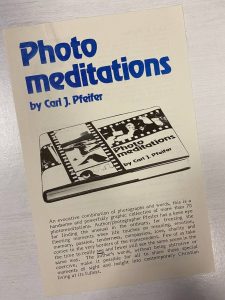

Similarly, Father Pfeifer was influenced by his interactions with Fr. Aloysius Heeg, SJ, who he met during his studies in the School of Divinity at St. Louis University, and instilled in him the importance of using pictures, stories, and free questioning in catechesis teaching, and would lead directly to his personal interest in photography. Years later Pfeifer would extend the approaches he used in his formal classroom into his Photomeditations series, appearing as a weekly National Catholic News Service syndicated column from 1974-1980 and published in book form in 1977. While some of the photos include religious imagery, such as rosary beads and crosses, the majority simply depict singular images of everyday things, places, and people that may normally be overlooked or taken for granted. The accompanying text, unique to each photo, asks readers to “meditate” on the image and the emotions, feelings, or lessons it may bring to their minds, allowing them the space to make connections to the teachings of their faith in their own way and time.

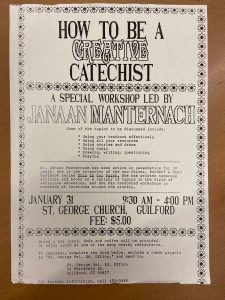

Together Manternach and Pfeifer would turn these quiet experiments into a national revolution in religious education through the publication of their Life, Love, Joy and This is Our Faith textbook series and other educational resources. However, this creative approach extended beyond simple materials or publications; for them the label “Creative Catechesis” was a mindset more than anything, one that formed the foundation of many of their talks and workshops over their nearly 3 decades of professional work, and not a one-size fits all approach. The creation, in their honor, of the Creative Catechist Award by their long-time publishing company Silver, Burdett, & Ginn in 2001 offers no better testament to their legacy. Growing in faith involves more than being able to repeat a system of beliefs; sometimes it involves quiet reflection on a story with a simple message, for as they so clearly reminded their audience in an April 2001 workshop handout in response to the question: Why Use Story?: “Jesus used it all the time.”

Meghan, I’m so glad someone else gets to experience this amazing collection! I hope you enjoy working with it as much as I did!