Hannah Kaufman is a Graduate Library Pre-Professional (GLP) at The Catholic University of America, who also works in Special Collections.

Since starting my position as the new archives GLP, I have been working on the finding aid for the USCCB/NCCB Secretariat for Cultural Diversity. Having never created a complicated finding aid before, I took one look at the 25 boxes that made up the collection (with more, Catholic University archivist John Shepherd assured me, possibly on the way) and felt a little overwhelmed. However, after spending a little time browsing other finding aids and getting acquainted with the boxes themselves, I began to feel a little better.

This collection could be easily divided into two distinct ‘series’ or categories within which archival material is organized. Although all diversity task forces were merged under a new Secretariat of Cultural Diversity in the Church, the Hispanic Catholics and Black Catholics subcommittees of USCCB were originally their own distinct entities and are thus easy to differentiate. Armed with a preliminary inventory done by a former practicum student, I set to work identifying which boxes contained which materials. A few things quickly stuck out to me. The materials devoted to Hispanic Catholics were generally older, and there were fewer to sort through. My still lingering trepidation over the amount of material I would be working with was certainly a part of my decision when deciding how to organize the collection, but in the end the materials’ age was what convinced me to put it first. All of the Hispanic Catholic materials date from the seventies and early eighties, with only a few exceptions. Meanwhile, the Black Catholics materials issue from the eighties up to the early two-thousands. Although within the series, material organization is prioritized alphabetically, I decided to organize the series chronologically, as it felt more intuitive to have the older organization first in the finding aid.

The Secretariat for Hispanic Affairs (directed by Paublo Sedillo for the duration of the papers currently held in the Catholic University Archives) came as a result of one of the recommendations of the First Encuentro. It called for the then USCCB Division for the Spanish Speaking be upgraded to that of a special office directly under the USCCB’s General Secretary. The Encuentros were events designed as a way of reaffirming the Hispanic Catholics’ place in the faith, both for themselves, and for the Catholic Church. Encuentros often spawned other events which drew off the energy the anticipation for these events wrought, such as the pilgrimage to the Shrine of Guadalupe, in Mexico, 1984. Each event culminated in the creation of a pastoral document presented to the church, with a plan for creating a more welcoming environment within the church for Hispanic Catholics, as well as expanding involvement within Hispanic Communities. A significant amount of materials in this collection are devoted to the planning and production of these Encuentro events.

But the Secretariat for Hispanic Affairs did much more than plan Encuentros. Other examples of material one can find in these records include campaigns to protect migrant workers, to fight against welfare cuts, to push for positive immigration reform, and to denounce racist policies. There are also pastorals, papers, and a large collection of audio visual materials containing, among other things, Spanish liturgy and sermons.

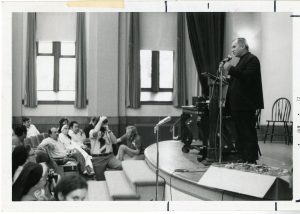

The Secretariat of African American Affairs papers hold some content similar to that of the Hispanic Affairs papers, in that it consists of the efforts of a group of people which had historically not been prioritized by the Catholic church working together to amplify their voices. These papers contain talks and interviews given or conducted by Beverly Carroll, surveys on the numbers of Black priests serving in the United states, and records of both Bishops’ Committee on African American Catholics materials and National Black Catholic Congresses.

Additionally, the collection deals with issues being faced by Black Americans both inside and outside of the church. There are several folders devoted to the effects of racism and ways to combat it, as well as the AIDS crisis, by which Black people were disproportionately affected. The collection contains ways to combat and ameliorate these issues, both through legislation and volunteer work, as well as through community support and prayer for victims.

There are also records for events and information distributed by the Secretariat of African American Affairs for Black History month, and research and materials on Black theology and Black liturgy, as well as publications such as The African Bible, or the Black Biblical Heritage, all of which seek to celebrate Black Catholics and demonstrate that their place in the faith has been there since its very beginnings.

Looking over my finding aid, you may notice that the first half, devoted to the Secretariat of Hispanic Affairs, is intensely specific. It seems almost as though each file has been labeled individually and put in its own folder. That’s because this is mostly what I did. As an archivist in training, I fell victim to the same mistake many new archivists do: over processing. This collection is important; I knew that and I didn’t want to miss anything, or cause a researcher to miss anything, through my negligence. By the time I reached the Beverly Carroll files, I knew better. Ms. Carroll was assiduous with her filing, and all the folder titles for the second half of the finding aid are predominantly of her own making. Indeed, it was Mrs. Carroll’s careful filing (she often wrote the location of the paper she wanted to preserve on the corner of the page with a ballpoint pen) which helped me realize I should be focusing more on the original order. This is not to say that Mr. Sedillo was not well organized, rather that sometimes you need something spelled out for you (in the corner of a page. With a ballpoint pen). After I realized this, I simply removed paper clips and staples and re-foldered them into acid free folders. I learned a few important lessons here. The first is to trust researchers to be able to find what they’re looking for, and the second is to learn when you can trust the original owner of the work you’re processing as well. After all, Mrs. Carroll had a good system, one that made sense to her and that she was careful to preserve. Why destroy that, when that organizational context adds so much to each piece of the collection?

One of the primary functions of an archive is to hold recorded history, so that someone can come back years later and examine that history. I cannot help but think about this purpose in conjunction with these two groups’ work to be recognized as they deserve in the Catholic church, to assert that they have always been valuable members of the Catholic community. They have always been here, and this collection is yet another resource that people can point to as documented evidence of a long term commitment by Black and Latinx Catholics to their committees, to their faith, and to themselves.