The following is a selection from Catholic University student Katie Coyle’s class paper on the Ivory Triptych, a piece of Renaissance-era art held by Special Collections at the University. Ms. Coyle’s piece was submitted as an assignment for Professor Tiffany Hunt’s course ART 272: The Cosmopolitan Renaissance and edited by University Archivist William J. Shepherd. The students used art from the University collections for their papers.

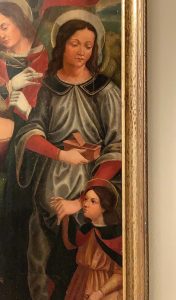

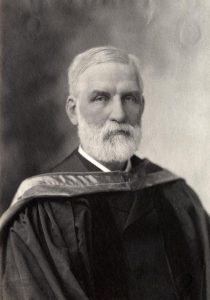

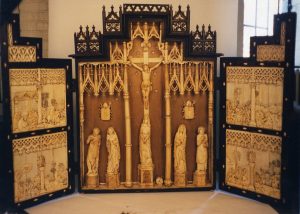

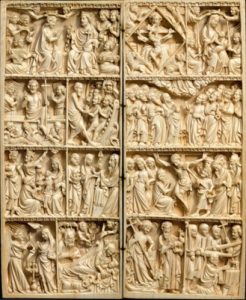

To understand the Renaissance and its global connections, one should look at a specific period object and its cultural influences. Although focused in Italy, the Renaissance encompassed cultural influences across the Mediterranean, Northern Europe, Africa, and the East and involved a combination of materials, styles, and images from various cultures and artistic traditions. The Ivory Triptych found in the Catholic University Special Collections is a visual representation of important elements of this global Renaissance. It is large at 42 ¾ by 33 ⅝ inches, depicting various Gospel scenes. Special Collections notes indicates it to be one of the largest known ivory triptychs. It is made of wooden panels covered with carved ivory elements displaying scenes of Christ, Mary, and various saints. Two small side panels in the front are fastened by two locking devices to keep them shut when necessary. Metal pieces are attached on the back wood panels to attach the piece to a wall as a hanging decoration. The artist and creation date are unknown, but it has been identified sixteenth century French. The donor, Rev. Arthur T. Connolly, an avid traveler and one of the most prominent benefactors represented in Special Collections, gifted it to Catholic University on May 5, 1917.

The original donation remarks include a description of the figural scenes and specific symbolic representations of the Ivory Triptych. It also contains a reference to its original placement (before being collected) as part of the back of a church altar, though the church or location in France is unknown. It was meant to be viewed most often in its open state because the elaborate and skillful decoration, including all of the ivory elements, are only visible when it is fully open. Although the Ivory Triptych originally served within a faith-based context of worship as a church altarpiece, it is now an object of curiosity and instruction. Since 2001, the Ivory Triptych has been loaned out to several Catholic University faculty members and placed in campus offices where it is a decorative object. Removing a fine art object like this from its original context presents challenges to research who made it and for what purpose. Attempting to understand its original role and placement is important to know its true context within its specific historical setting.

In the sixteenth century, African ivory was particularly rare, especially within France, making it highly desirable for religious art. During the Renaissance, an increasing desire for exotic materials like ivory helped develop a strong trade network connecting Africa, Europe, and the East. Along with this, stylistic ideas spread and deepened cosmopolitan connections. Christian elites used art objects like small diptychs and triptychs in their homes for private worship. Larger ivories like the Ivory Triptych would be commissioned by the wealthy for various churches. Commissions were a vital aspect of Renaissance-era art as a way for artists to sell their work and for patrons to demonstrate their class standing. Art selected by the wealthy and displayed for the public in an open setting like a church, the Ivory Triptych would be on the altar for viewing with its imagery highlighting Gospel stories for a mass audience that was not literate.

Other French ivory objects from the same period include plaques, diptychs, triptychs, and polyptychs. For example, the Diptych with Scenes of the Life of Christ and the Virgin, Saint Michael, John the Baptist, Thomas Becket, and the Trinity from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, ca. 1350, depict the life of Christ and various saints. Scenes of the Annunciation, Nativity, Adoration of the Magi, Presentation in the Temple, and the Resurrection are all present in the small 10 by 8 ⅚ inch diptych. The Ivory Triptych fostered a sacred atmosphere where onlookers could participate in Gospel scenes. The Adoration of the Magi and the Flight into Egypt are located in the top of the left panel. The bottom of the left panel features Christ’s Baptism and the Agony in the Garden. The top of the right panel portrays the Betrayal of Christ and the Carrying of the Cross. In the bottom right, the Entombment and Resurrection of Christ are portrayed. All of the side panels are divided into these four sections, with a column or jardiniere (floral planter) diving the section into two halves, each with a biblical story. The center of the triptych is Christ crucified with Mary directly below the cross on a pedestal. On her left are St. John the Baptist and St. Margaret of Antioch, and St. John the Divine and Mary Magdalene are on her right. Above the carved figures are ivory stars and bishops’ coats of arms. These symbols were easily recognizable to any viewer, regardless of literacy and social class.

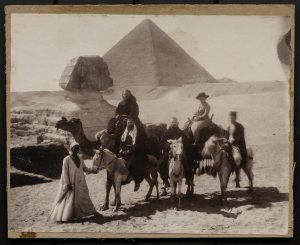

Symbolism within the scenes points directly to an Eastern influence as devout Christians aimed to connect with a distant land and ancient past. Artists used symbols associated with the assumed story settings. In the Flight to Egypt the Holy Family approaches a distant setting with large palm trees in a rocky desert, symbols assumed to portray Egypt. The ornamentation on the wood and the ivory elements framing the scenes also shows a distinctly Eastern influence. On the side panels above each scene, geometric shapes in curves and points are imposed, reflecting the common use of Islamic patterns where figural imagery and depiction in a religious context were forbidden. Westerners were able to partially understand the necessary concept of ornamentation for the sake of worship and fascination with these unique styles of decoration took hold in Italy and France. By the time of the sixteenth century, Islamic decorative quality combined with French architectural tradition, can be seen in the architectural elements in the central panel of the Ivory Triptych. The detailed ornate style of the pinnacles and spires surrounding Christ are representative of the Islamic tradition of decoration and geometric elements. Along with many of the other art objects in the Catholic University collection, the Ivory Triptych points to a universality of Renaissance influence that stretched beyond Italy.

Bibliography

Baxandall, Michael. ‘Conditions of Trade,’ Painting and Experience. pp. 1-27.

Belting, Hans. ‘Perspective as a Question of Images’ Paths between East and West,’ Florence and Baghdad, 2011. pp. 13-25; 42-54.

Brotton, Jerry and Jardine, Lisa. ‘Exchanging Identity: Breaching Boundaries of Renaissance Europe,’ Global Interests: Renaissance Art between East and West, Reaktion, 2000. 11-62.

‘Ivory Triptych,’ ACUA Museum Collections: New Museum Collection, Washington DC, June 1995.

‘Remarks, No. Museum 1292,’ Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America, October 17, 1927.