Guest blogger, Dr. Cecilia Moore, is an Associate Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Dayton and faculty member of the Degree Program for the Institute for Black Catholic Studies at Xavier University of Louisiana. Dr. Moore with Dr. C. Vanessa White of the Catholic Theological Union and Fr. Paul Marshall, S.M., Rector of the University Dayton, co-edited Songs of Our Hearts and Meditations of Our Souls: Prayers for Black Catholics, St. Anthony Messenger Press (2006).

In August 2015, Dr. Kathleen Dorsey Bellow, Father Kenneth Taylor, and I spent four days in the basement of the Saint Meinrad Seminary Library. We were there to sort, curate, and pack more than 40 years of archives documenting the lives of black Catholics in the United States that Father Cyprian Davis, O.S.B. saved. When we made the plans to do this work, we expected that Father Cyprian would be working alongside us, but he had died that May. Graciously and generously, Archabbot Justin Duvall, O.S.B. allowed us to go forward with the plan and agreed to cover the shipping costs. By the time we finished, Father Taylor had a van full of boxes containing the archives of the National Black Catholic Clergy Caucus (NBCCC) to be donated to the Archives of the University of Notre Dame. There were also boxes of documents destined for the Archives of Xavier University of Louisiana for the Institute for Black Catholic Studies (IBCS) Collection and for the Black Catholic Theological Symposium (BCTS) Collection, a small collection of documents for the Archives of the University of St. Thomas for the National Office of Black Catholics Collection, and a very large of pile of boxes containing documents, ephemera, papers, books, and material culture, that are now the Cyprian Davis, O.S.B. Papers of the American Catholic History Research Center and University Archives, part of Special Collections at the Catholic University of America.

How and why we came to do this work started a year earlier when Dr. Bellow and I visited Father Cyprian at Saint Meinrad in July 2014. We both had studied with him at the IBCS and later became his colleagues as we joined the IBCS faculty and then served as IBCS administrators. Over our years working together at the IBCS, we became friends with Fr. Cyprian, but it had been while since we had enjoyed his fine company in person.

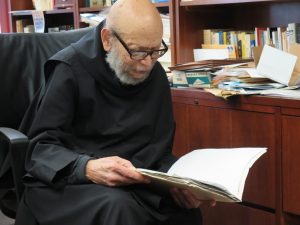

During our visit, Fr. Cyprian hosted us for refreshments and conversation in his spacious and comfortable office. It was filled with books, journals, works-in-progress, photographs of family and friends, and art. It was the place where he wrote class lectures, homilies, articles, talks, and of course, The History of Black Catholics in the United States. It was also where he engaged in his love of reading and conversation. We had the best time with him. Among the many things we discussed were his work revising The History of Black Catholics in the United States, politics, movies, books, and the need to find permanent homes for the NBCCC and BCTS archives which he had served as archivist for since 1968 and 1978 respectively. These archives were held in a storage room in the basement of the Saint Meinrad Seminary Library. When we volunteered to help him complete this mission, Father Cyprian gladly accepted our offer.

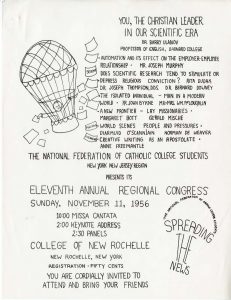

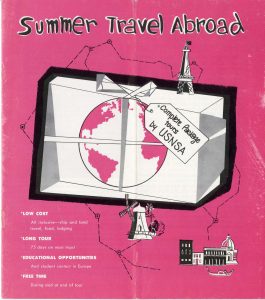

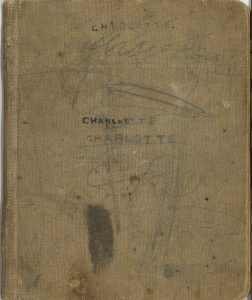

We returned to St. Meinrad in December 2014 to assess the work we needed to do. At that time, Father Cyprian took us to the storage room and we got our first look at the historical treasures he had saved over the past 46 years. And, he had saved quite a lot. A wall of deep shelves was loaded with large and small boxes of formal documents, letters, magazines, newsletters, bulletins, memos, conference programs, newspaper articles, books, tapes, films, photographs, event programs, manuscripts, notes, cards, etc. It was amazing. We spent hours taking boxes down and looking at their contents with Father Cyprian. What a trip down “memory lane.” We knew many of the people attached to or responsible for the history that we held in our hands. Many of the women and men at the heart of the contents of these archives had died, so we spent time remembering them, what made them fit for the battles they fought on behalf of black Catholics, and the personal qualities that made them so memorable and missed. Others were still living, and we had a good time looking at their younger selves and discussing how their ministries in the black Catholic community had changed over the years in emphasis, intensity, and status. As we did this preliminary assessment, it became clear that there was a lot in the Saint Meinrad Library storage room that did not properly belong to the NBCCC, the BCTS, or the IBCS.

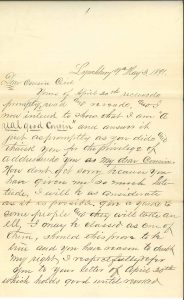

There was a fourth archives that was hard to define because it was so eclectic. It contained things that Father Cyprian had either written or helped to write and edit. It documented the people and the places that over the past 50 years that had called on Father Cyprian to “tell” them their history. Letters and cards revealed the vast network of people, from many different backgrounds, who reached out to him – to send him things that they thought were important to black Catholic history that he could use to write more of the history, to seek his advice about their work on black Catholic history, to tell him how much his work meant to them, their students, and their parishes, or to challenge him on points of the history he had written. There were also dissertations, theses, conference papers, and articles written by people who were directly inspired to pursue research in black Catholic history by Father Cyprian. By the end of the day, it was clear that Father Cyprian had an archives that needed a permanent home too.

When we suggested this to him, he demurred at first, but after thinking about it for a while he agreed with us and told us that he wanted his papers to be donated to the Catholic University of America. He was happy that this trove of primary and secondary sources would assist future generations of historians committed to black Catholic history to continue researching, writing, and teaching an-ever more contextualized and rich history of Catholics of African descent in the United States.