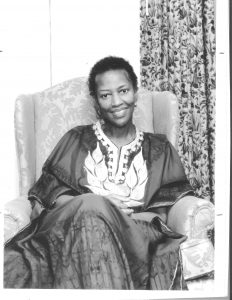

Sr. Bowman’s life was one rich with literature, music, education, and spirituality. A scholar and teacher to elementary- to college-age students – and even bishops. Bowman contributed to Catholic education, liturgy, and experience through her outreach and writings on music and education. And like Father Cyprian Davis, she was both an educator of and advocate for the Black Catholic experience – its creativity, art, history, and contributions to the Church.

Born in 1937 and raised in Canton, Mississippi, Bertha Bowman converted to Catholicism at the age of nine – convincing her parents to do likewise. By the age of 15, she decided to join the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, taking the religious name “Thea” or “of God”. She entered her postulancy at the order’s motherhouse in La Crosse, Wisconsin in 1953. Having witnessed police brutality and mob actions against members of her community growing up, Bowman’s parents were understandably nervous about their young daughter departing to join an all-white order. In a 1989 interview, Bowman recounts that her father warned her, “They’re not going to like you up there, the only black in the middle of all the whites.” Her response: “I’m going to make them like me.”[1]

While Bowman struggled with discrimination and health issues during the next decade of her life, she would quickly prove herself a skilled educator, serving with her order in Wisconsin, and later, her home state of Mississippi. Arriving at Catholic University in the late 1960s, she entered Washington at a key moment in the post-Vatican II Church, Civil Rights Movement, and Women’s Rights Movement. As a Black Catholic religious sister, she was well placed to speak to the overlapping issues of all three movements.

During her tenure in Washington, Bowman gained further insight into her identity as an African-American religious sister. Her connections with the broader Church and global African community – both the diaspora and African students – reignited a passion that she would carry with her throughout the remainder of her life. She not only established the first class on Black literature on campus, but she became an advocate for African-American Catholicism beyond Catholic University. She soon became a speaker of the experience of the African community with the Catholic Church, both the trauma of the past and present as well as the creative output of the present and future. Rhetoric and music were key interests of Sr. Bowman, both of which informed her approach to her teaching and spiritual practices. As she told CUA Magazine in 1990:

While studying literary theory, methodology and criticism at CUA I began to realize the extent to which music encodes values, history and faith of my people. While studying medieval ballads, I read an author who said the oral literary tradition no longer exists. I wrote a paper showing how the oral tradition is alive and well in the black community and how music is a way we have of preserving history and teaching values.

Bowman’s passion for teaching, rhetoric, and music was exemplified in the presentations she offered both on and off campus during her time in DC. She delivered a 1968 address on Black education at Howard University.[1] As recalled by the CUA English faculty, Bowman would perform African-American Gospel spirituals in traditional regalia for her fellow Catholic University students and faculty. These performances would then be followed by a talk on the rhetorical purpose of the performance’s various components from the words to the physical gestures.[2]

As both a MA and later doctoral student in English language and literature, she wrote her MA thesis (1969) and doctoral dissertation (1972) on St. Thomas More’s A Dialogue of Comfort Against Tribulation. She was drawn to the rhetorical style of this text that More composed during his time imprisoned in the Tower of London.

After finishing at Catholic University, Bowman returned to Mississippi, continuing to serve as an educator and advocate. She not only remained involved with her local communities, but traveled the nation (and world) speaking about Black music and literature within the Catholic Church. Diagnosed with breast cancer in 1984, one of her final lectures was before the U.S. Catholic bishops in 1989. During this talk she performed an African-American spiritual, and invited the assembled bishops to stand, hold hands, and sing along. Bowman passed away in 1990, but her legacy of teaching, outreach, and advocacy continues as represented by her cause for canonization and scholarships in her name.

[1] Smith, Charlene & John Feister. Thea’s Song: The Life of Thea Bowman. Orbis Books, 106-9.

[2] Smith & Feister, 38.

Thank you for this informative article. I joined CUA faculty in 1972-73, the year after Sr. Thea earned her PhD. I saw her in person once, when she she gave a spirited address to my group of SNDs.