On July 13, 2020, the Washington Redskins announced that they would finally be retiring the team name—a move that the team’s owner, Dan Snyder, had repeatedly resisted, perhaps most vehemently in 2013. His exact words: “We’ll never change the name. […] It’s that simple. NEVER — you can use caps.”

Controversy over the team’s name and logo stems not only from the term “redskin” but from the use of American Indian iconography in mascots, in general. My own high school in Montgomery County, Maryland—Poolesville High School—used the Indians as its mascot from 1911 all the way up until 2002, when the community’s vote to keep the problematic mascot had to be overruled by the county’s Board of Education; at that time Poolesville reluctantly adopted the Falcons as its new mascot. The term “redskin,” meanwhile, has been likened to the N-word: a term denoting skin color which through years of derogatory use has become offensive. Wikipedia has an entire page devoted to the Washington Redskins name controversy; it traces the dispute back to the 1960s, when it was presumably raised in connection with the Civil Rights Movement.

Since the murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, however, calls for racial justice have been falling less on deaf ears. Dr. Maria Mazzenga, Curator of the American Catholic History Research Center, sees the reconsideration of the team name as part of a broader “historical consciousness shift generated in part by Floyd’s murder and the demonstrations that followed”; the reconsideration came about in earnest after the @Redskins participated in #BlackOutTuesday on June 2, at which time others were quick to call out the team’s hypocrisy. A team with a racial slur for a name had no leg to stand on when it came to standing against racism, critics argued.

Located in the nation’s capital, The Catholic University of America (CatholicU) has a short but momentous history with the Washington, D.C., NFL (National Football League) team. Established in Boston as the Braves in 1932, the football team was renamed the Redskins in 1933; the new name was devised to help avoid confusion with a local pro baseball team (which was also called the Braves) without giving up the reference to indigenous Americans. In February of 1937, the Redskins relocated to Washington, D.C., where the CatholicU Redbirds were enjoying a heyday.

In his centennial history of Catholic University, C. Joseph Nuesse refers to the arrival of athletic director Arthur J. “Dutch” Bergman in 1930 as the beginning of “a new era” (Neusse 274). Under Rector James H. Ryan and Dutch Bergman, ““Big time” intercollegiate football became a prime objective of the university’s athletic program” (Neusse 274). According to CatholicU alumnus and local historian Robert P. Malesky, “Bergman was paid a higher salary than any faculty member, causing considerable consternation, though his winning record over his decade at the school caused an equal amount of joy” (Malesky 91).

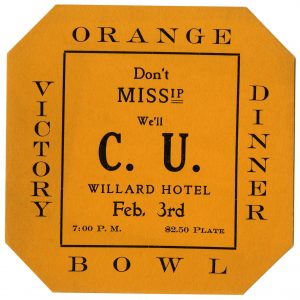

On New Year’s Day, 1936, the CatholicU Cardinals narrowly defeated Ole Miss in the second-ever Orange Bowl (the first was held on January 1, 1935). The score was 20–19. Malesky describes the game as a nail-biter: “CUA jumped out to a 20–6 lead, but then Ole Miss came back strong, scoring 13 points late in the game. A missed point after a touchdown for Mississippi was the critical difference” (Malesky 92). At the helm was Bergman. The 1936 yearbook also lists the Assistant Backfield Coach as recent alumnus Thomas Whelan—a star athlete who entered Catholic University in 1929 on a football scholarship and who upon graduation (in 1932) played professionally for the Pittsburgh Pirates, soon-to-be Steelers. Incidentally, Whelan and Bergman also teamed up off the field; between 1936 and 1938, the two ran a tavern together in the Brookland neighborhood adjacent to the CatholicU campus.

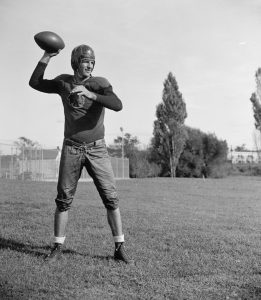

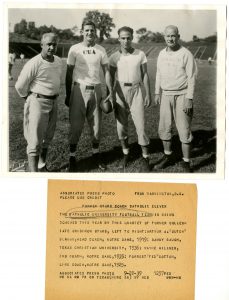

A 1939 photograph shows the thickset Bergman standing alongside his assistant coaches in the CatholicU stadium, which had been dedicated in 1924 under Rector Thomas J. Shahan and which was situated more or less in the area now occupied by the Pryzbyla Center and the Columbus Law School. The two coaches standing in the center of the photograph were contemporary “stars with the Washington Redskins football team”: quarterback “Slingin’” Sammy Baugh—a “future hall of famer”—and Wayne Millner, an offensive and defensive end who had played for Notre Dame before going pro (Malesky 91). According to Malesky, “Baugh was not a full-time coach but did come out a few afternoons during the season to instruct CUA’s quarterbacks” (Malesky 91). The fourth man in the photograph is Forrest Cotton, another Notre Dame alumnus. Of course Bergman was himself a noted alumnus of the Fighting Irish. Standing about five feet eight inches tall and weighing 145 pounds, he earned the nicknames Little Dutch and The Flying Dutchman for his quickness. His roommate was the legendary George Gipp, a fact which he joked would overshadow any of his own accomplishments.

In CatholicU history, Bergman goes down as the “all-time winningest varsity football coach” and to this day holds “the highest winning percentage (.649) in school history” (McManes). According to the same article from CatholicAthletics.com, “CUA dropped football in 1941 because of the outbreak of World War II and didn’t field another team until 1947.” In that interim, Bergman went on to coach the Redskins in the 1943 season (at which time Sammy Baugh was still quarterback). In 1948, Bergman became the manager of the D.C. Armory—the corporation that lobbied for the construction of RFK Stadium in Washington, D.C. At the time of his death in 1972, Bergman was still managing the D.C. Armory and RFK Stadium. As Washington Post sports writer Bob Addie mused, “The handsome silver-haired man who died Friday night (August 18, 1972) got his wish—he never retired.”

Works Cited

Brady, Erik. “Daniel Snyder says Redskins will never change name.” USA TODAY Sports. https://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/nfl/redskins/2013/05/09/washington-redskins-daniel-snyder/2148127/. May 9, 2013. Accessed July 20, 2020.

Malesky, Robert P. The Catholic University of America. Charleston, SC, Arcadia Publishing, 2010.

McManes, Chris. “Former coach Dutch Bergman distinguished himself in all walks of life.” Catholic University Cardinals. https://www.catholicathletics.com/sports/fball/2012-13/releases/dutch_berman_feature_story. December 14, 2012. Accessed July 20, 2020.

Neusse, C. Joseph. The Catholic University of America: A Centennial History. Washington, D.C., The Catholic University of America Press, 1990.