As explained in a previous blog post, Special Collections at The Catholic University of America consists of four departments: rare books, museum, university archives, and the manuscript collection, otherwise known as The American Catholic History Research Collection. Although ‘manuscript’ literally means handwritten, ‘manuscript collection’ is used by archivists, curators, and librarians to refer to collections of mixed media in which unpublished materials predominate, including correspondence, meeting minutes, typescripts, photographs, diaries, and scrapbooks. This describes personal papers but also the institutional records of our outside or non-Catholic University donors such as Catholic Charities USA, National Catholic Education Association (NCEA), and the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB), including their earlier incarnations like their World War I era National Catholic War Council. Among the USCCB records the most important are those of the Office of the General Secretary (OGS), sometimes called the Executive Department, and these contain the American Catholic Church’s involvement in almost every major issue of the twentieth century.

One of the most fascinating episodes recounted and inventoried in the OGS records, replete with detailed documents and photographs, is that of the American Catholic participation in the Papal Relief Mission to Russia, 1922-1923. Churchill’s famous 1939 quip defining Russia as “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma,” (1) could be aptly paraphrased as “a puzzle, wrapped in a conundrum, inside a perplexity” when applied to the Papal Relief Mission of a decade and a half earlier. This was the first international aid mission of the Roman Catholic Church, undertaken to alleviate the starving children of Bolshevik Russia, the core of the nascent Communist Soviet Union, the emerging archenemy of the Catholic Church. The Famine of 1921-1923, focused in areas of the Volga, Ukraine, and northern Caucasus afflicted as many as 16 million people, perhaps killing as many as 5 million. It is with bitter irony that we mark this one hundredth anniversary with a renewed war with attending death and destruction, not to mention looming hunger, in this same sad corner of Eastern Europe.

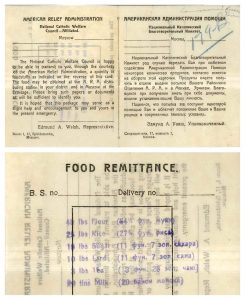

Prior to the famine, Russia had suffered three and a half years of World War I and the Civil Wars of 1918–1920 with millions of casualties, both military and civilian. The various warring elements arbitrarily seized food from civilians to supply their armies and deny it to their enemies. The Bolshevik government requisitioned supplies from the peasantry offer little in exchange, prompting peasants, especially the more wealthy ones, called Kulaks, to reduce crop production and sell any surplus to the Black Market. Initially aid from outside Soviet Russia was rejected. The American Relief Administration (ARA), formed to help victims of starvation of World War I, offered assistance to Lenin in 1919 on condition that they hand out food impartially, but Lenin refused this as interference in Russian internal affairs. He was, however, convinced by this as well as other famines and unrest to reverse policy and permitted relief organizations to bring aid. The ARA had an organization set up in Poland relieving famine that had started there in late 1919.

Under the auspices of the ARA, headed by Commerce Secretary and future President, Herbert Hoover, the Papal Relief Mission to Russia by 1922 was feeding approximately 158,000 persons a day. The pivotal figure between American Catholics and the Roman Curia, and subsequently between the Vatican and the Bolsheviks, was Edmund Aloysius Walsh, S.J., founder of the first American School of Diplomacy, at Georgetown University. (2) Walsh served as papal emissary in charge of this mission, which, among other duties, entailed liaising with the ARA, keeping the Vatican informed, and negotiating with the Bolsheviks regarding the church’s position within a communist society. Stateside, Walsh was backed by the National Catholic Welfare Council (NCWC), ably led by Paulist priest and Catholic University alum, John Burke, who helped focus American Catholic relief efforts. Overall, Walsh’s experience provides a firsthand view of the Bolshevik world view and insight into the manner in which the Bolshevik Revolution was understood, or not understood, by the Vatican. Therefore, in spite of the good will that the mission’s success earned for the Vatican, efforts to establish diplomatic relations ultimately failed because the gulf between Catholicism and Communism was too great.

For more information on how to access NCWC/USCCB records, please contact us at lib-archives@cua.edu

(1) See also Churchill by Himself (2013), Chapter 10, Russia, page 143, Broadcast, London, 1 October 1939.

(2) For more on Edmund Walsh, see also McNamara, Patrick (2005). A Catholic Cold War: Edmund A. Walsh, S.J., and the Politics of American Anticommunism. New York: Fordham University Press and Marisa Patulli Trythall, ‘”Russia’s Misfortune Offers Humanitarians a Splendid Opportunity”: Jesuits, Communism, and the Russian Famine, Journal of Jesuit Studies, 2018 (5:1), pp. 71-96.

(3) Thanks to SM, BM, and HK for their assistance.