The nineteenth century was a period of rapid growth and change for England and America, and one can find a microcosm of these changes reflected in the English novel, in both the pages themselves, and the culture around printing their printing and distribution. Further advancements in printing, and intense industrialization had made books cheaper than ever to produce and ease of access naturally spurred an increase of interest. Lending libraries began to spring up all over England, where users could pay a small fee to receive access to a communal collection of novels. Throughout the nineteenth century, but particularly during the Victorian era of literature (lasting from 1837-1901) the novel blossomed, coming into its popularity just in time to help document the culture of a society diving headfirst into modernity.

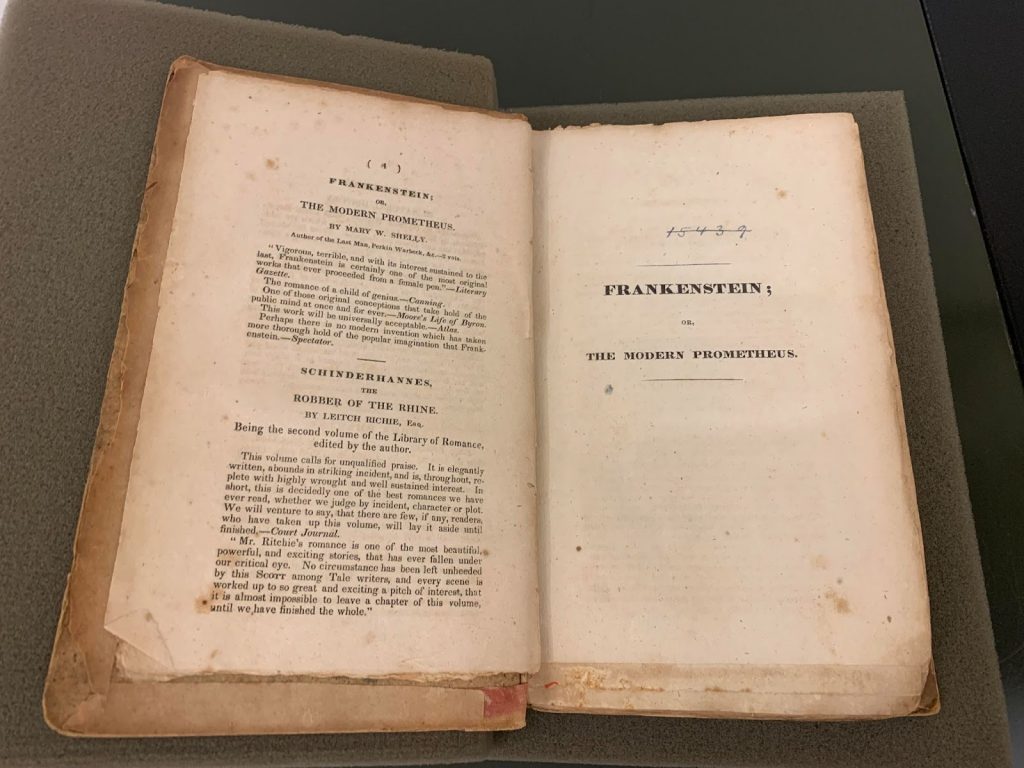

Despite the relative opulence that industrialism brought with it, many people felt an understandable skepticism towards a society that seemed to have forsaken pastoral life for a life crushed into the bustle of polluted cities, toiling away at dangerous machines, gradually allowing the beauty of the natural world to be rendered strange, carved up for wailing steam engines and smoggy factories. Mary Shelley was a writer of the Romantic movement, known for venerating the wonder of the natural world, and she viewed this zeal for industry with a certain amount of skepticism. In her novel Frankenstein, first published in 1818, the monster is cobbled together from various bodies, with its parts being selected for beauty. Yet despite it being made of only the most beautiful bits and pieces its creator, Victor Frankenstein, could find, the end result is something grotesque. Frankenstein cannot hope, even with all his scientific arts, to match the beauty that comes naturally to the world. Instead he creates a mockery. A first edition of this work, of which only 500 were printed, sold last September for a record breaking $1.17 million. Catholic University’s special collections cannot boast to have such a rare copy, but we do own a first American edition, printed in 1833 and generally believed to be pirated from the original 1818 British text. (Pirated in this context means that American publishers set unauthorized copies of the text by lifting it from a book published overseas. Clearly, the “industrial spirit” was alive and well in America as well.)

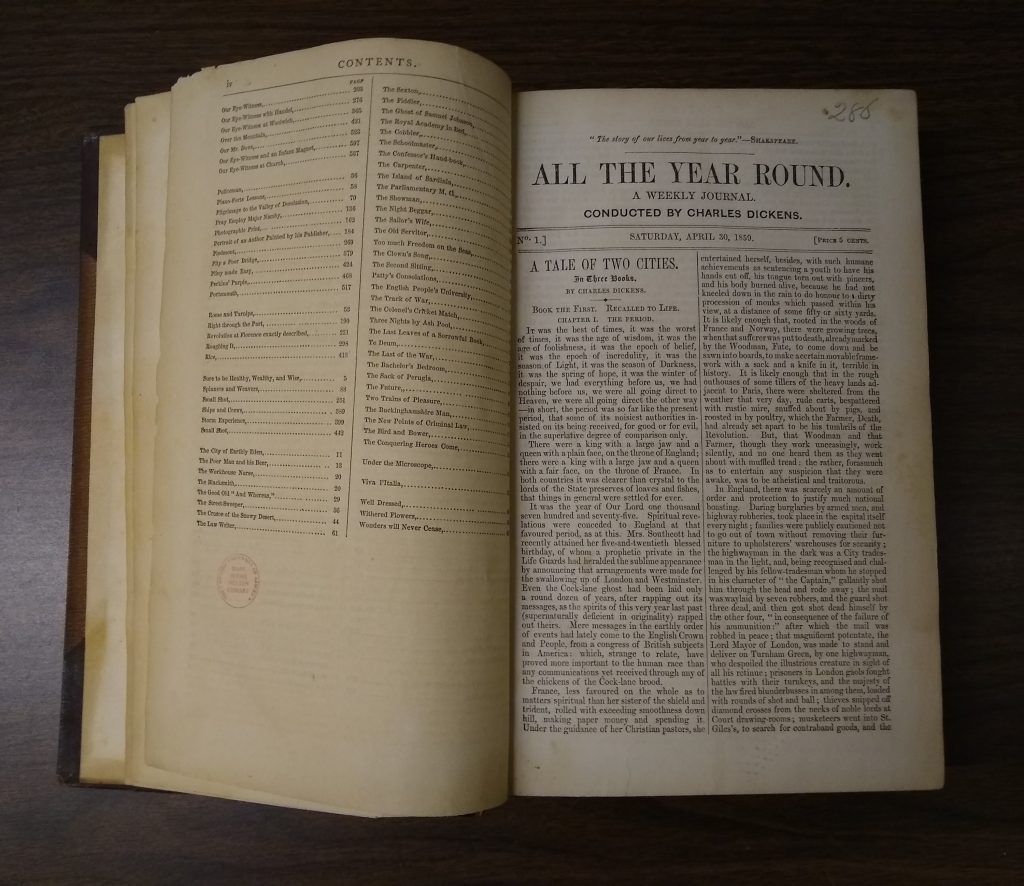

Our copy of Frankenstein was printed in Philadelphia by Carey, Lea & Blanchard. This is the same press which was publishing Charles Dickens’ first book, The Pickwick Papers, before the man had even finished writing them. Given that Dickens dedicated the book to the lawyer Tomas Talfourd for his work on copyright laws in Britain, this seems in particularly poor taste but in fact, pirated texts of foreign novels were incredibly common in the United States. Dickens, on his tour of America in 1837, campaigned heavily against this practice, citing the wrongs it inflicted upon already underpaid authors and their families, but to no avail. Indeed Dickens was, and is, famous for his championing of London’s poor, and could speak first hand to their suffering, having grown up in poverty, and worked in factories as a child to help support his family. Two of his later novels, Great Expectations and A Tale of Two Cities, which, among other topics, explore the universal hardship of extreme poverty, can be found serialized in the weekly journal All the Year Round. The journal was owned and run by Dickens himself and a full collection can be found in Special Collections.

America may have been home to a bustling business of pirated publications, but as the nineteenth century pressed on, its history and culture became increasingly re-entwined with Britain’s own and these themes of transatlantic cultural exchange made their presence known in the literature. And not all of it was uncomplimentary. The writer Henry James often explored themes of American idealism and naivete, mixed with its reputation for forward boldness through the characters of young American women, such as Isabel Archer in The Portrait of a Lady. An expansive collection of American and British first editions of the works of Henry James are available in the Catholic University Special Collections, as part of the Richard N. Foley collection. The late Professor taught in the English department here at Catholic University from 1940 until 1974 and his collection was acquired by Rare Books in 1982.

America fostered a reputation for embracing freedom, even from its colonization. It offered refuge to those religious dissenters who could not practice their faith as they liked amongst the Anglican church. But even this was changing. In George Eliot’s Victorian pastoral masterpiece, Middlemarch, the characters express their concerns over land rights and railroads. Yet in the background of these concerns, there are often references to “the Catholic question,” and what to do about it. In 1791, practicing Catholicism in England was legalized, and in 1829, parliament voted in favor of the Catholic Emancipation Act, which restored most civil rights to Catholics. Although Roman Catholicism remained something of a minority, the church did manage to gain some notable converts, the first of which was John Henry Newman. As anti-Catholic sentiment rose, his autobiography, Apologia pro vita sua was one of the pieces of literature which helped render Catholics more sympathetic to the average Englishman.

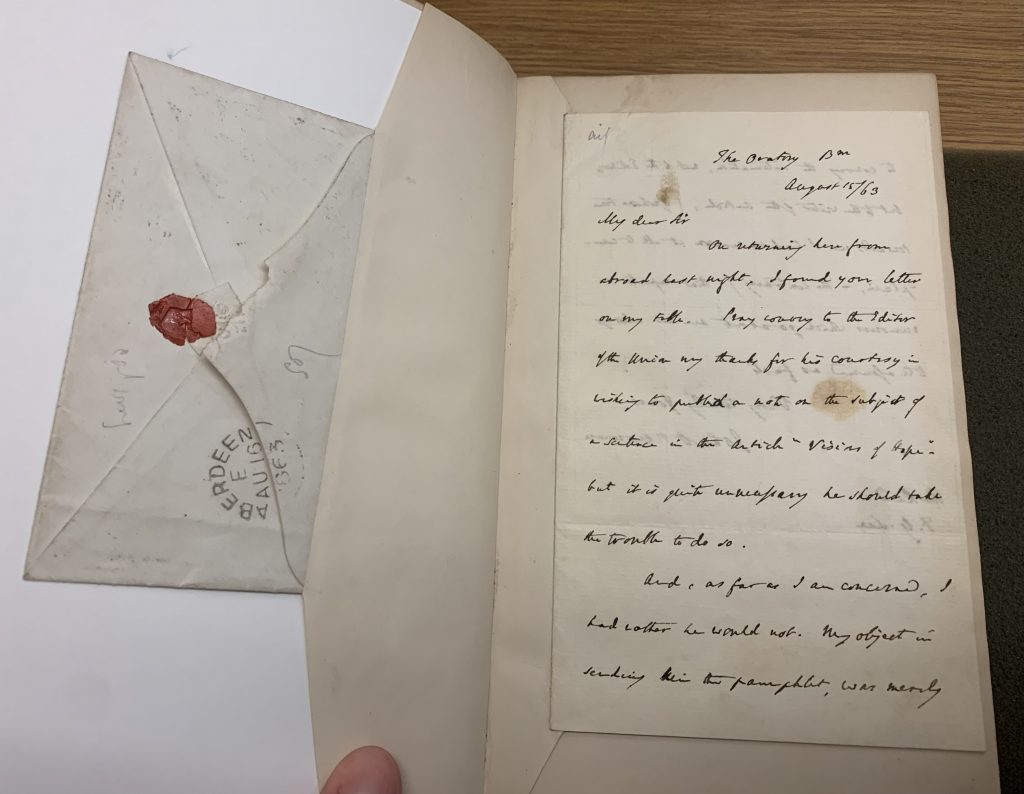

Cardinal Newman had another piece of writing which, while perhaps not achieving the same lofty heights as Apologia pro vita sua, is certainly very dear to us here at Catholic University. Upon our founding, Catholic University’s first chancellor, James Cardinal Gibbons, received a letter of congratulations from Cardinal Newman. This letter is a cherished piece of CatholicU history, and held in a secure place in the Catholic University Special Collections, where it keeps good company with the other works mentioned in this blog post, along with numerous other wonderful treasures. If you would like to visit them sometime, drop us a line. We are a library after all, and unlike the Victorian lending libraries of old, we won’t even charge you.