The following is a selection from Catholic University student Christopher Vitale’s class paper on the Pieta, a piece of Renaissance-era art held by Special Collections at the University. Mr. Vitale’s piece was submitted as an assignment for Professor Tiffany Hunt’s course ART 272: The Cosmopolitan Renaissance and edited by University Archivist William J. Shepherd. The students used art from the University collections for their papers.

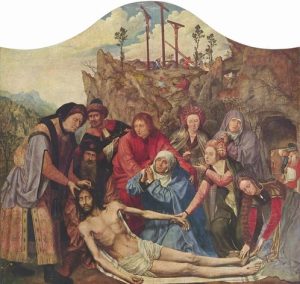

I was a little anxious at being informed that I would be required to select and study an object of Renaissance art from the Catholic University Special Collections. I reflected that I am a studio art major so maybe it would be a good idea to choose an object that relates to my artistic practice. I strongly identify as a painter, and specifically as an oil painter, as it is truly my passion. I also realized the spiritual nature of this project. Before all else, I am a Roman Catholic. Expressing and engaging with my religious beliefs is both the foremost joy and the pinnacle duty of my life. A marriage between my artistic attractions and my religious objectives yielded the ultimate result of my selection: the late 15th or early 16th century Pieta by Quentin Metsys (or Massys), a stunning work of Christian-based Northern Renaissance oil on wood painting.

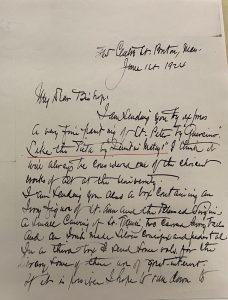

The accession file from Special Collections reveals the historical information relating to the Pieta’s provenance. Of particular interest is a handwritten letter addressed to Bishop Thomas J. Shahan, the fourth rector of the University and an auxiliary bishop of the archdiocese of Baltimore, sent by Rev. Arthur T. Connolly on December 17, 1919. Connolly assured Bishop Shahan that he would send “the painting of the Virgin [and] dead Christ by Quentin [Metsys]” shortly. Five days later, on December 22, the Bishop’s secretary returned a letter confirming that the Bishop’s office had received Connolly’s note and would “look out for the shipments referred to.” These details help us answer fundamental questions that should accompany any inquisitive mind when viewing or thinking about a historical piece of art, such as, “Why is this Renaissance painting here? How did it get here? Where did it come from?”

Looking more closely at those handwritten letters reveals additional clues, though it is nearly impossible to recognize every word due to Arthur Connolly’s scribbled handwriting, akin to cracking the code of ancient hieroglyphs. In a secondary letter dated June 1, 1924, Connolly explained that he would again send art objects, among these “an ivory figure of St. Ann and the Blessed Virgin, an Irish made silver crucifix and pedestal… and, interestingly, “a very fine painting of Saint Peter by Guercino” (i.e. the distinguished Italian Baroque artist Giovanni Francesco Barbieri). By encouraging Shahan to use the Pieta as a point of measurement, Connolly underscored his perception of the elevated nature of the Metsys piece and demonstrated that he was intent on presenting Shahan, and the wider University community, with ‘the cream of the crop’ in respect to historical artworks. The fact that Connolly and Shahan were writing and sending successive, handwritten notes to each other, and that Connolly addressed Bishop Shahan with affectionate language suggests that the pair were friends, which is why these sorts of objects wound up at Catholic University.

After all, that is precisely what friends do-they send things to each other. Today, of course, we have text messages, phone calls, emails, and Amazon delivery services that enable us to exchange conversations, information, and gifts with one another instantaneously, but in the early 20th century, a prime way to maintain friendships was by swapping physical correspondence letters and gifting things the other might care about or which might be useful towards a more ambitious end, such as amassing a University collection. Bishop Thomas Shahan was also the founder of the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, an influential American house of worship and a monumental sanctuary for religious artworks (today it holds the largest collection of contemporary ecclesiastical art in the United States). Donating art objects would fuel the archives, libraries, collections, and exhibits of the University, which in turn serve to strengthen the institution as a center for research, academic discourse, and historical preservation. It’s benefactors like Connolly who were responsible for filling the catalogs with objects and artworks which increase the University’s visibility within Academia.

Documents and memos in the accession file disclose that the painting was moved around a couple of times, it eventually found a home in Nugent Hall, which is both the private residence of the university president as well as the headquarters for his offices. It is currently displayed in a spacious and finely decorated sitting room complete with couches, armchairs, and coffee tables. Also featured in that room is a small portrait etching by Rembrandt. Since Rembrandt is among the most honored and influential figures in art history, my theory is that the Pieta functions, like the Rembrandt, to impress visitors of the president, serves as a testament to the University’s academic and historical legitimacy, and underscores both the theological roots and artistic strengths of the institution

What the object file also includes is a short biography of Metsys by Stanley Ferber from the McGraw-Hill Dictionary of Art. Ferber wrote that Metsys employed “a conscious archaism, both sensitive and perceptive, which he ultimately synthesized with late-15th-century Italian developments, especially those of Leonardo.” Though the Pieta depicts a moment of violence and sorrow as a bloodied Christ has been removed from the Cross and placed in his Blessed Mother’s arms, there is an undeniable sense of peace and a visual softness in the rendering of the figures and the overall composition. This accompanies the attention to detail characteristic of Flemish art, as articulated by the three crosses on the hill far in the distance behind the Virgin, with tiny figures standing at their base, as well as the crown of thorns, the nails, and the sponge soaked in wine that appear in the foreground of the piece. In addition to helping me better conceive of the nature of Renaissance art, my research into the object and its file has allowed me to develop a deeper appreciation for the application of historical artworks in a modern context