The following post was authored by Graduate Library Pre-Professional (GLP), Juan-Pablo Gonzalez.

Video interview with Art student Alex Huntley on the steps of Aquinas Hall.

It was the fall of 2017, my first semester as a graduate student and my first working in the University Archives. During this time, I had the special interest to create a program to increase the archival holdings that pertained to student life, with attention towards under-represented persons at the university. I wanted these students to have a permanent imprint on the memory of this institution so they would not only be subjects of history but creators and determiners of it. I also wanted to provide a basis for researchers to better understand the evolution of student life at The Catholic University of America (CUA) since its inception.

I had been inspired by the archives’ collection of early year books and the early photographs of students. I was transported to a time where Michigan Avenue was made of dirt and traffic consisted of a horse-drawn carriage or two. The photographic collections evoked but a cursory notion of what it must have been like to live this translucent existence amongst the wealthy, stately looking young men of the early university and what it must have been like to walk the streets of a city whose grand edifices and monuments were largely built by black men like me, who had been held in brutal bondage, just a few years prior, in order to bring this great city and nation to bear.

Through these photos, I was able to explore the lives of the earliest generations of students and I was able to clearly understand how the social nature of student life had evolved from earliest reaches of Jim Crow Washington, D.C. to the free flowing dalliances of the 1970s—a la the CUA Bong Club…

It was the materiality of the photographic print medium and how it had been meticulously cataloged, logically organized, preserved, and given a framework for efficient research access that had allowed me to explore the intricacy of time and place and to impart informative meaning onto my contemporaneous experience here. What I saw was that people who looked like me had been here since the inception of the university and have helped to shape the university intellectually and socially across many generations.

The Archive is a space where memory, remembrance, materiality, and visibility intertwine. There is no memory without materiality (be it through the physical visceral materiality of the oral edifice known as our mouth, be it documentary, or be it as an object); likewise, there is no remembrance without visibility; and there is no visibility without the performance of materiality.

For me, this realization is anchored by a revelatory observation made by Dr. Condoleezza Rice in her memoir, No Higher Honor: A Memoir of My Years in Washington that I often reflect on when thinking of the importance of archival materials: “Today’s headlines and history’s judgment are rarely the same. If you are too attentive to the former, you will most certainly not do the hard work of securing the latter.”

In this regard, an archive can be seen as a threshing floor that is situated between today’s headlines and history’s judgement and it is on this floor that we must search for the meaning of the latest artistic expressions, acquired by the university archives.

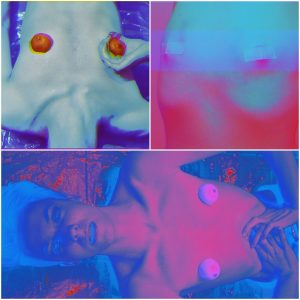

We are pleased to offer the Catholic University community access to the photographic art of recent graduate Alex Huntley—an art student who identifies as Transman.

The acquisition of Alex’s art work imbibes the university archive with standard-bearing materials through which future researchers will be able to gain an understanding of this inchoate period of great social transition, in which we now find ourselves.

The Catholic University Art Department has always been an academic unit driven by a vision to protect the freedom of individual artistic expression. This vision was established fifty-one years ago and this vision is what allows for today’s art students to enjoy tremendous agency of expression here at Catholic University.

In 1968, the Art Department’s faculty were called upon to make their cases as to whether or not the Art Department would integrate with The School of Architecture.

For many of the 1968 faculty members the idea of integrating with The School of Architecture was intriguing but would inevitably mean the total disintegration of philosophy and praxis. In fact, Alexander Giampietro, an Associate Professor of Art at Catholic University in 1968, composed a letter (Giampietro, 1968) detailing why the Art Department needed to remain its own separate department. He stated that “Fine Arts and Architecture are in a state of crisis [and] Man is seeking questioningly for a way out of the chaos that is impending,” because society had failed to “…cope with man the creature as an end.”

The inability of some social spaces to accommodate for the individual is what the art faculty felt was the fuel for man’s rebellion through art, which “…is but a tribute to the human spirit trying to find a way out,” and that this is all “…a sign that man is hungry in his heart.” (Giampietro, 1968)

The impending chaos that the 1968 faculty feared was Collectivism. Giampietro’s (1968) premise rested squarely on the anti-collectivist ideas of Eric Kahler’s 1968 monograph The Disintegration of Form in the Arts, where he quotes from the following passage:

The overwhelming preponderance of collectivity with its scientific, technological and economic machinery, the daily flow of new discoveries and inventions that perpetually change aspects and habits of thought and practice, the increasing incapacity of individual consciousness to cope with the abstract anarchy of its environment, and its surrender to a collective consciousness that operates anonymously and diffusely in our social and intellectual institutions—all this has shifted the center of gravity of our world from existential to functional, instrumental, and mechanical ways of life. (p. 3)

Giampietro goes on to make collectivism analogous to such “conditions” as the “mini-midi-maxi skirt, long beards, psychedelic happenings, and John Cage’s ‘Music’—a rather astute observation because even norm challenging trends are ironically collectivist, devoid of individuality, and thus rendered unremarkable and disposable by scale.

We are now half a century removed from the world of the 1968 art department and Giampietro’s fight for the individuality of the artist has ensured that their hungry heart can be satiated through the freedom of unfettered artistic expression, which has become a mechanism of visibility, permanency, recognition, self-narration, and self-definition for students like Alex, here at the Catholic University of America’s Art Department.

Our University Archivist, W. J. Shepherd, has instilled in me an infectious appreciation for all things Churchill. And in the spirit of that enlightenment, I leave you at a contemplative position from which to examine Alex’s art work—through the lens of Winston Churchill’s view of the arc of history: “For my part, I consider that it will be found much better by all Parties to leave the past to history, especially as I propose to write that history.” Alex has written (His)tory at The Catholic University of America, during a time where society has attempted to author his reality, and through these artistic expressions, generations to come will have a sociological key to understanding who were as people and who we were grappling to become.

Alex’s works will be available in print and may be checked-out to the Catholic University Community. His work will also be preserved in digital format through the university archives digital archive.