Mary Ann Glendon tends to inspire contradictions.

The Learned Hand Professor of Law at Harvard University and a former United States Ambassador to the Holy See, Glendon has been labelled a modest “water-and-soap type” at one extreme and “the Pope’s bombshell” at the other (see Notes 1 and 2).

Much of the confusion about Glendon stems from the fact that she doesn’t blend in with her surroundings—either as a pro-lifer at Harvard or as a woman in the male-dominated circles of the legal profession and the Catholic Church.

Twice she has been the very first woman in her role; in 1968, she became the first woman to serve on the faculty of Boston College Law School, and in 1995, the first woman to head a papal delegation (3). On the latter occasion, The Irish Times reported:

“The slight, blond 56 year old Harvard Law professor does not match any stereotypes. With a background in civil rights in Mississippi and an interest in new economic approaches to the third world, she is a feminist and she is a radical, but she is not a radical feminist” (4).

Ironically, the one label that faithfully describes Glendon is the very thing that makes her so “iconoclastic” (5). She is first and foremost a devout Catholic.

Nowhere is Glendon more of a misfit than in American politics; she routinely self-identifies as politically “homeless” (6). As a champion of Catholic social teaching, her views often straddle progressive and conservative party platforms—rendering her inscrutable to many Americans accustomed to thinking in binary.

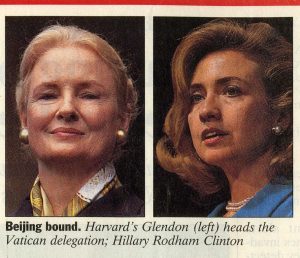

Leading the Holy See’s delegation to Beijing for the United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women in September of 1995 was a turning point for Glendon—not to mention a historic moment for the Catholic Church. That September in Beijing marked both the first time a woman had been appointed to represent the Vatican and the first time a Holy See delegation had been composed of a majority of women (14 out of 22 members).

For Glendon, Beijing was at once the culmination of her pro-life activism (rooted in Catholic social teaching and comparative law scholarship) and the springboard for her subsequent papal and presidential appointments. During the George W. Bush administration, Glendon was asked to serve on the U.S. President’s Council on Bioethics (2001-2004) and was later appointed U.S. Ambassador to the Holy See (2008-2009). Meanwhile, in 2004, Glendon was appointed President of the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences (PASS)—becoming only the second woman ever to occupy such a high-ranking post in the Catholic Church’s hierarchy (7).

Beijing raised Glendon’s profile beyond Boston in dramatic fashion. Journalists reporting on the 1995 Women’s Conference relish her emergence as a foil for another prominent blonde American woman: then-First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton, who made a cameo appearance at the Conference.

Other journalists take it upon themselves to reconcile Glendon’s appearance with her anomalous backstory. A front page article in Catholic Exponent attempts to scuff up the popular, whitewashed portrait of Glendon—one that leaps to conclusions based on her blonde hair and her ivy league office—by divulging some of the messy details of her personal life:

“She knows problems of single and working mothers first hand. After a civil marriage in the 1960s ended in divorce when her daughter Elizabeth was 2, she was a single mother for three years before she married attorney Edward R. Lev, who is Jewish, in a Catholic ceremony in 1970. They had a daughter, Katherine, in 1971, and adopted another daughter, Sarah, a Korean orphan, in 1973” (8).

Complicating Glendon in this way preemptively dispels the holier-than-thou air of which she has sometimes been accused by those to whom she comes across as prim.

The Catholic University Archives holds a number of collections related to women’s organizations and famous figures like Mother Teresa, but markedly few that document the careers of individual Catholic laywomen. The Mary Ann Glendon Papers fill that gap—providing valuable insight into the Boston Catholic intellectual milieu; American politics; the development of neoconservative Catholic thought; the Church’s position on so-called women’s issues; and the life of a contemporary.

To learn more about the Mary Ann Glendon Papers, please see the newly-created Finding Aid.

Notes

- Cesare De Carlo, “Mary Ann la tradizionalista sfida Hillary la liberal,” il Resto del Carlino (Bologna, Italy), September 4, 1995.

- Paul Sheehan, “Pope’s bombshell,” The Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney, Australia), June 1-2, 2002; and Paul Gray, “The Pope’s Bombshell,” discovery (Melbourne, Australia), June 27, 2002.

- “Mary Ann Glendon Named 1st Woman Professor at BC,” The Berkshire Eagle (Pittsfield, MA), May 6, 1968.

- Lorna Siggins, “Straight talker on the Vatican team looks to “third millennium feminism,”” The Irish Times (Dublin, Ireland), September 9, 1995.

- James Loeffler, “How Mike Pompeo’s Professors Hijacked a Scholarly Debate: Human rights and the academic right,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, July 31, 2019.

- Dick Lehr, “Writing her own party line: Recruited by the Vatican, rebuffed by Bush, the Harvard Law prof defies definition,” The Boston Globe, December 11, 1996.

- The first predated Glendon’s appointment by less than a year: Letizia Pani Ermini, President of the Pontifical Academy of Archaeology.

- Cindy Wooden, “Harvard prof heads Vatican delegation to Beijing,” Catholic Exponent (Youngstown, Ohio), September 8th, 1995.