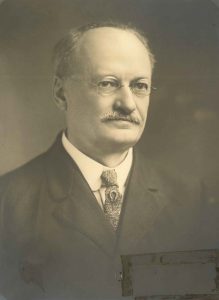

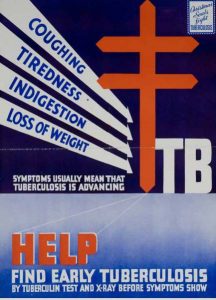

As historians, archivists, and librarians, we address many subjects, including the history of disease. As the world of 2020 faces the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, it is worthwhile to consider another serious infectious disease that afflicted the world more than a century ago—and the man who, after surviving his own diagnosis of the disease, dedicated himself to its prevention and treatment. The disease is tuberculosis, which primarily affects the lungs with bacteria spread person to person through tiny droplets released into the air through coughing and sneezing. The person who pioneered the research and treatment of this deadly disease was Dr. Lawrence Francis Flick (1856-1938). A devout Roman Catholic and German-American from western Pennsylvania, Flick was a dedicated medical doctor as well as a serious historian of his Church. His papers, which reside in the Special Collections of The Catholic University of America in Washington, D. C. document his work in both his fields of interest.

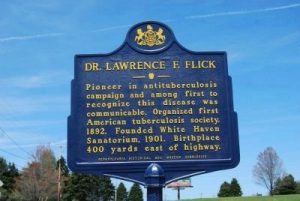

The ninth of twelve children, Flick was born on August 10, 1856, near Carrolltown in Cambria County, Pennsylvania. His parents were German immigrants with roots in Bavaria, John Flick and Elizabeth Sharbaugh (or Schabacher). He was educated at St. Vincent’s College in Latrobe, Pennsylvania. It was also an adjunct to a Bavarian Benedictine Monastery, which trained priests for the order as well as the Pittsburgh diocese. After contracting Pulmonary Tuberculosis, the version that affects the lungs, Flick was forced to drop out and return home to recuperate. Somewhat better but still in poor health, Flick enrolled at Philadelphia’s Jefferson Medical College in 1877, the same year that the college became one of the first teaching medical colleges in the United States. Flick graduated in 1879 as a medical doctor and interned at Blockley, the Philadelphia charity hospital. Flick also devoted several years to curing himself, including a tour of the American west and eating an experimental diet. Apparently cured by 1883, Flick returned permanently to Philadelphia and had a remarkable career as a specialist in tuberculosis, and its prevention and treatment.[1]

Flick’s studies prompted him to argue that the disease was contagious and not hereditary, which contradicted the current school of thought. His efforts to isolate ‘consumptives,’ as those suffering from tuberculosis were then called, in special hospitals known as sanitariums, and to register their cases, was controversial, and opposed by many within the medical profession. Between 1892 and 1910, Flick’s efforts to educate the public prompted him to found the Pennsylvania Society for Prevention of Tuberculosis; the Free Hospital for Poor Consumptives; the Henry Phipps Institute for the Study, Prevention, and Treatment of Tuberculosis, where he was President and Medical Director from 1903 to 1910; and a sanitarium at White Haven, Pennsylvania, that he directed until 1935. His fellow Roman Catholics from all levels of society were generous in their contributions and assistance. Flick was also a promoter of the National Association for Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis (1904) and of its International Congress on Tuberculosis (1908). In addition to his fight against Tuberculosis, Flick was also in the forefront of combating the Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1918 in Philadelphia.

What lesson then does Flick have for us in these times of uncertainty brought on by this pandemic? He is an example of how one person can make a difference in research, education, and, most importantly, the treatment of a terrible disease that resulted in its eventual mitigation. Flick said “Tuberculosis takes only the quitters,” those who got discouraged and gave up the struggle.[2] Flick was a fighter who would not be defeated. Perhaps someone reading this blog post will be such a person, a new Flick to defeat the Coronavirus, or some other as yet unheard of pestilence. We can only hope.

[1] James J. Walsh. ‘Dr. Lawrence F. Flick,’ The Commonweal, August 26, 1938, p. 445.

[2] Raymond Schmandt. ‘The Friendship between Bishop Regis Canevin and Dr. Lawrence Flick of Philadelphia,’ The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine (61:4), October 1978, pp. 284-286.

[3] Special Collections at CUA also houses the records of many Catholic organizations fighting disease and disaster, including the National Catholic War Council, United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Catholic Charities USA, and the Society of St. Vincent de Paul. Also, thanks to staff for their assistance.

First citation, James J. Walsh, was a distant cousin and took my father, then at Fordham, under his wing, suggesting he study medicine not at Fordham but at the College of Physicians and Surgeons, soon to become part of Columbia University. My father did residency under him at St. Vincent’s, now sadly shuttered.

Very interesting and informative article. Thank you for sharing your professional knowledge. Now you have one regular visitor to your site for new topics.