This week marks one hundred years since the foundation stone for the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception was laid on September 23, 1920. But, like Rome, the Shrine wasn’t built in a day. In this blogpost, I’ll focus on the early history of the Shrine—from its inception up until the intermission in its construction beginning in 1931.

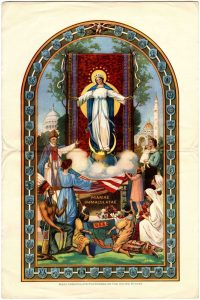

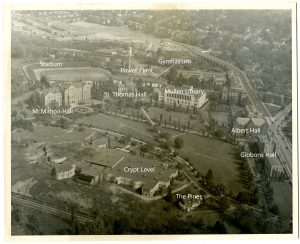

“IDEA MANY YEARS OLD” pronounced the Salve Regina Press, the publisher of the Shrine’s fundraising bulletin, on August 1, 1924; after the Blessed Virgin Mary, under her title of the Immaculate Conception, had been designated as the patroness of the United States in 1847, whispers of a “fitting architectural symbol of this dedication” supposedly occurred at the Second Plenary Council of the Catholic Church in 1866 and surfaced again at the Third Plenary Council in 1884. The establishment of a national Catholic university in 1887 only lent urgency to the matter of a patronal church. When The Catholic University of America first opened in 1889, the campus community patronized the chapel in Caldwell (then-known as Divinity) Hall. As early as July 1910, Thomas Joseph Shahan, the fourth rector of the University (1909–1928), expressed his desire for a full-fledged University Church: “Professors and books shed a dry light,” he explained (himself a professor), “but a glorious Church sheds a warm emotional, sacramental light” (Letter to Mr. Jenkins). Dubbed the “Rector-builder,” Shahan championed much of the campus construction in those days—perhaps to a fault: “A university is a society of men, not buildings,” chided his successor, Monsignor James H. Ryan (Nuesse 171; Malesky 90). In any case, the Shrine was his pride and joy. In 1913, Pope Pius X gave Shahan his blessing along with $400 (Tweed 49).

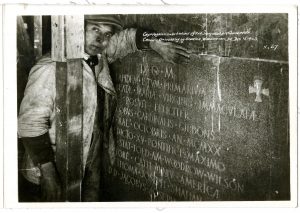

By at least one account, the fact that the foundation stone arrived in one piece for the festivities seven years later was a miracle; it was driven more than 1,500 miles from New Hampshire down to Washington, D.C. (taking a very winding path) on the back of a new-fangled green and gold “Auto Truck” whose brakes supposedly failed at one point during the journey. The donor of the stone, James Joseph Sexton, remarked “how lucky we were to travel so far […] without accident,” adding “I shall always reverence the Blessed Virgin Mary as I have told many […] how she protected us at Perryville Road when our Auto Truck dashed down the hill at fully 40 miles an hour” (“On This Day in History“).

Cardinal James Gibbons, Archbishop of Baltimore, presided over the laying of the foundation stone—as he had on numerous other occasions at the University (including the inaugural event on May 24, 1888, when the cornerstone of Caldwell Hall was laid). The next day, The Washington Post described the ceremony as “one of the most notable religious events ever witnessed in the National Capital,” and reported that “10,000 persons thronged the university campus to view the spectacle” (“Vast Shrine Is Begun“). But conspicuously absent from the crowd that day were some of the Shrine’s earliest and most ardent supporters: laywomen like Lucy Shattuck Hoffman who made up the National Organization of Catholic Women (NOCW) (Tweed 35).

Hoffman had played a prominent part in the prehistory of the Shrine (between 1911 and 1918), not only as the founder of the NOCW but also as the mother of an established architect who in 1915 submitted the “plaster model of Gothic design” pictured in many of the Shrine’s early promotional materials (Tweed 32). As such, Hoffman apparently took for granted the fact that her son would get the commission. But in 1918, the University’s Board of Trustees decided to abandon the Gothic in favor of a Romanesque design. For whatever reason, the devoted members of the NOCW were not made privy to the Trustees’ decision and were left instead to read about it in the same fundraising periodical they helped distribute (Tweed 33). Hoffman felt betrayed. The members of the NOCW’s New York chapter resigned in solidarity, and just like that, one of the first national organizations of Catholic women “abruptly disbanded” (Tweed 34).

Interestingly, the foundation stone was laid “only thirty-six days after women won the right to vote,” but the climate at the ceremony was not celebratory (Tweed 17). In his sermon that afternoon, the bishop of Duluth accused women of “seeking a freedom that is excessive” (“Vast Shrine Is Begun“). His apparent lack of support for women seems incongruous given that the Shrine was not only marketed explicitly to “America’s Marys,” but was also in large part the product of women’s fundraising efforts.

In the absence of any traditional American ecclesiastical style, the architectural firm Maginnis and Walsh felt that “the U.S. cultural condition allowed—even demanded—freedom to experiment” (Tweed 25). Hence the “Byzantine beach ball” we know today (Tweed 5). Some have suggested that Shahan and the architects rejected a Gothic design because the National Cathedral, already underway in the District of Columbia, was Gothic. Others have suggested that they sought an alternative design because Gothic structures took too long to build—an ironic objection, considering the Shrine was only completed “according to its original architectural and iconographic plans” upon the dedication of the Trinity Dome mosaic in 2017: four score and seventeen years after the foundation stone was laid in 1920 (“Dedication of the Trinity Dome“).

Construction on the crypt level did not actually begin until three years later, in 1923. The first public Mass was held in the crypt church on Easter Sunday in 1924. Later that year, the Salve Regina Press reported: “In this crypt, incomplete though it is, already ordinations have been held and thousands of pilgrims have attended Mass, often said while the hammers of workmen punctuated the singing of the priest” (“Glories of the Crypt“). Presciently, the closing paragraph of the same August 1, 1924 issue of the Salve Regina Press exactly predicts future delays: “When the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception will be completed is as much a problem as the great cathedral-builders of the Middle Ages faced. Business depressions, wars—many things—may intervene.”

For years, Shahan and his secretary, the Reverend Bernard A. McKenna, were the “two master minds” of the Shrine project, but shortly after Shahan’s death in 1932, McKenna—the Shrine’s first director—returned to his pastoral work in Philadelphia (Tweed 29–30). The loss of leadership was compounded by the onset of the Great Depression and the United States’ eventual entry into WWII; the project lay dormant after the crypt level was completed in 1931.

For more than two decades the lower church evoked the “Half sunk” Ozymandias; at one time, the bishop of Reno complained that it “remained a shapeless bulk of masonry half-buried in the ground” (Tweed 42). Following a 23-year hiatus, construction resumed in 1954 and the superstructure was formally dedicated on November 20, 1959. For more on that story, stay tuned for the centennial in 2059!

Although the foundation stone isn’t visible from the outside, you can see it by visiting what is now the Oratory of Our Lady of Antipolo, or #17 on the page-two map from this 1931 guide book.

Works Cited

“Dedication of the Trinity Dome,” https://www.nationalshrine.org/history/#timeline.

“Glories of the Crypt,” The National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception (Salve Regina Press, August 1, 1924). Thomas Joseph Shahan Papers. Collection 69, Box 39, Folder 6.

“Idea Many Years Old.” The National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception (Salve Regina Press, August 1, 1924). Thomas Joseph Shahan Papers. Collection 69, Box 39, Folder 6.

Letter to Mr. Jenkins, dated July 28, 1910. Thomas Joseph Shahan Papers. Collection 69, Box 39, Folder 6.

Malesky, Robert P. The Catholic University of America. Arcadia, 2010.

Nuesse, C. Joseph. The Catholic University of America: A Centennial History. CUA Press, 1990.

“On This Day in History,” September 23, 2019, https://www.nationalshrine.org/blog/on-this-day-in-history-the-laying-of-the-basilicas-foundation-stone/

Tweed, Thomas A. America’s Church: The National Shrine and Catholic Presence in the Nation’s Capital. Oxford, 2011.

“Vast Shrine Is Begun,” The Washington Post, September 24, 1920. The National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception Collection. Collection 48, Box 9, Folder 1.

I have always believed the main reason for abandoning a Gothic design was the already underway, decidedly Gothic, Protestant Episcopal National Cathedral.