Guest author is Steve Rosswurm, Professor of History, Emeritus, at Lake Forest College, and author of The FBI and the Catholic Church (2009), The CIO’s Left-Led Unions (1992), and Arms, Country and Class (1987).

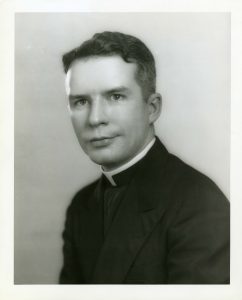

Archbishop Wilton Gregory, recently named the first Afro-American cardinal of the Church, more than once has pointed to Monsignor John M. Hayes (1906-2002) as the cleric who inspired him to become a priest. Prior to that, Hayes also had “attracted” another young man to the Catholic priesthood: the sociologist and novelist Father Andrew Greeley, who dedicated Golden Years, part of the O’Malley family saga, to the monsignor.

Hayes did much in Chicago besides influencing Gregory and Greeley. He served for years at St. Carthage, where he first encountered the Gregory family, and for even longer at Epiphany from he retired in 1976. He was involved in the civil rights movement – heading up a group of priests who went to Selma in 1965 – and other social justice issues. He was named a monsignor in 1963.

The four years that Hayes spent at the Social Action Department (SAD) of the National Catholic Welfare Conference, though, are often forgotten. This installment of the archivist’s nook focuses on his tenure there.

For two reasons, Hayes was the only person the SAD considered for their new position. First, as a Chicago labor priest mentored by Monsignor Reynold Hillenbrand, he had actively supported union organizing drives and strikes. Hayes, moreover, had taught at Catholic labor schools and participated in the Catholic Worker movement. His talk in 1938 at Summer School for Social action for Priests not only nicely summarized the possibilities for social-action work for priests, but also solidified his reputation throughout the country.

Second, Hayes was well suited for SAD’s future plans. It had spear-headed the Church’s turn to the Catholic working class that had begun in 1935. This move, a way to “restore all things in Christ” by implementing Catholic social teaching as laid out in Rerum Novarum (1891) and Quadragesimo Anno (1931), focused on educating and supporting clerics in the drive for unionization in industries where Catholics comprised a large proportion of workers. As a way of doing this, the SAD had organized and overseen priests’ labor schools throughout the country. It also had acted as a clearing house and organizing center for labor priests’ local activities, especially in the industrial heartland. The SAD staff, including Monsignor John A. Ryan and Father Raymond McGowan, were spread thin by the time Hayes arrived in 1940.

Hayes accomplished at least three significant things during his tenure at the SAD from 1940 through early 1944. One of his first acts proved to be the longest lasting and most significant. On December 1, 1940, the first issue of Social Action Notes for Priests appeared. For clerics only, this newsletter connected labor priests throughout the country, keeping them informed, notifying them of resources, boosting their spirits, and, influencing their thinking. By June, 1944, about 700 were on the subscription list; that number more than doubled in the next two years and continued to grow well into the 1950s.

Second, Hayes engaged in an extraordinary correspondence with labor priests throughout the country. In an effort to search out the names of priests interested in social action, he wrote inquiry letters to many areas of the country. He also sent out detailed questionnaires concerning clerical labor activity and provided summary reports in Social Action Notes.

Much of Hayes’ correspondence, though, originated in response to letters from throughout the country. Labor priests, both veterans and novices, wrote to him because he had information and answers. Hayes provided advice, shared resources and contacts, spread the news about successes and defeats, and offered encouragement. When necessary, moreover, he intervened in the internecine warfare that periodically broke out in Catholic labor circles.

Amidst all this work, finally, Hayes produced a remarkable paper: “Priests and Reconstruction – a Few Thoughts.” Derived from Hayes’ immersion in CIO organizing campaigns in Chicago, his study of current economic conditions, and his work with Hillenbrand, “Priests and Reconstruction” decisively re-conceptualized Catholic thinking about society and salvation.

Hayes began with “radical evils” in America’s “economic side of life” because they were both “fundamental and causative.” The “physical results” of these evils – some institutional and others individual – were an “inequitable distribution of property” and “inadequate incomes.” The “resulting spiritual loss” was sizeable: “economic immorality” involved “at least in some cases, serious sin;” “the working out of the system” leaves “people so materially depressed as to handicap virtuous living” or “impels the well-to-do and others to obsession with business or dishonesty and injustice.” “[S]piritual losses” were “accentuated” among the “poor” and ‘reformers,’ Hayes argued, when the Church was “indifferent to, or ineffective in, attacking the causes, not to speak of alleviating existing hardships.”

How ought the Church and its clergy respond? “[I]ndividual righteousness,” of course, deserved attention, but, drawing upon Papal teaching, Hayes argued that “We should influence social-economic life, directly and indirectly.” It was true that “Church exists” to “unite men with God in Heaven,” but this was a “long earth-bound process.” The work of “building a good natural order” could “not be distinguished in practice” from that of “enhancing supernatural life.”

Hayes’ assertion that the road to salvation was a “long earth-bound process” meant not a retreat from the world into spiritual enclaves, but rather a courageous encounter with it was an extraordinarily important insight and breakthrough. “Priests and Reconstruction” more generally indicated the theological and sociological bases upon which the Church would operate for the next decade or so.

Hayes, however, was not at the SAD during that period. Sometime in late 1943 or early 1944, he was diagnosed with tuberculosis, so, at his doctor’s recommendation, he went to San Antonio, which the pro-CIO Bishop Robert E. Lucey headed. There, after recovering, he taught at Incarnate Word University, served as Lucey’s social action director, and regularly wrote columns for the diocesan paper. In 1953, he returned to Chicago.

Coda. Another Chicago priest, Father George Higgins, replaced Hayes at the SAD and remained there until 1980. For many of those years, he chaired the department.

Thank you Professor Rosswurm for your piece on Msgr. John M. Hayes. I have such fond memories of him post 1976 after my first communion. I knew very little about his active years before retirement. Truly inspirational in a time when more of us need to step up for social justice.