With the launch of One Hundred Years of Catholic Schools (1893–1993), I’m pleased to announce the formal completion of a project that I’ve been working on since last spring. The latest addition to the American Catholic History Classroom, One Hundred Years of Catholic Schools (1893–1993) is an online resource that explores the history of American Catholic schools at the elementary and secondary levels between the 1890s and the 1990s. (See this illustrated timeline for a rundown.) Featuring a selection of documents and objects from Catholic University’s Special Collections (chiefly the American Catholic History Research Center and University Archives), the site is meant to offer an introductory overview of the topic with an eye towards promoting primary source literacy.

Better yet, it comes just in time for Catholic Schools Week 2021! Between the 1890s and the 1990s, the advent of Catholic Schools Week in 1973 signified an important change in tune. When they were first established in the late nineteenth century, Catholic schools offered a religious minority safe haven from the Protestant-dominated and overtly prejudiced public schools. But for a multitude of reasons coalescing around Vatican II, community-based schools catering to Catholic immigrants began to fade out in the mid twentieth century. As enrollments fell and operating costs rose, Catholic Schools Week came on the scene under the guise of a “self-help” project. The idea was to rebrand Catholic schools not as a last resort for a persecuted minority, but as an enticing alternative approach to education for anyone who lacked confidence in the public school system. The operative word was “choice.” This year, the annual promotional campaign is being held from Sunday, January 31st to Saturday, February 6th. (As an aside, February 6th also happens to be my grandma Rosemary Hogg’s 95th birthday; she earned her degree in library science at Catholic University in 1981).

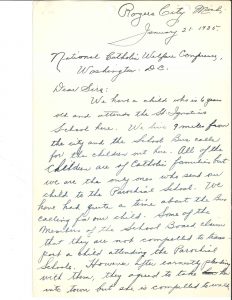

Now, I’d be the first to admit that studying the development of America’s second-largest school system can be dry. In general, I’ve hoped to imbue the institutional history of American Catholic schools with some personality. Perhaps the strongest example from the site is this January 21, 1935 letter to the National Catholic Welfare Conference (today’s USCCB), in which Mrs. H. C. Schmidt of Rogers City, Michigan describes the school bus situation for her six-year-old daughter:

… We have had quite a time about the Bus calling for our child. Some of the members of the School Board claim that they are not compelled to transport a child attending the Parochial Schools. However after earnestly pleading with them, they agreed to take her into town but she is compelled to walk from the Public School to the Catholic School which is a distance of about one mile. It hardly seems fair. The child is cold when she gets off the Bus and has to start on her long walk. Then again she walks to the Public School at night and she is cold when she starts on her long drive. The winters are very severe here.

The issue of bus transportation was just one facet of the debate over the constitutionality of public funding for private schools, which hinged on the Establishment Clause; in the next decade it would reach the Supreme Court in Everson v. Board of Education (1947).

On top of pathos, Mrs. Schmidt’s letter includes an interesting allusion to “K.K.K. lawmakers”—making it a rich primary source that demands to be understood in its historical context. Although the Ku Klux Klan is commonly associated with the American South, it was active throughout the North and Northwest in the 1920s and 1930s; it’s notable that the Schmidt family resides in Michigan, where in 1920 a referendum on compulsory public education received a surprising amount of support—foreshadowing the events in 1922 that led to the most famous of all Supreme Court cases having to do with Catholic schools. The Oregon School Case (the subject of another Classroom site!) grew out of a Klan-backed bill requiring most school-age children to attend public schools. Writing ten years after the Supreme Court unanimously declared the Oregon School Law unconstitutional in 1925, Mrs. Schmidt gives us a glimpse into her ongoing struggle.

Through glimpses like these, I hope future users will come to appreciate the history of American Catholic schools as I eventually did: as an underdog, coming-of-age story.