Guest blogger Katherine DeFonzo is a Graduate Library Pre-Professional (GLP) working in the Semitics/ICOR Department at Catholic University.

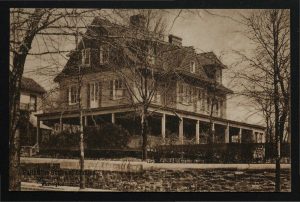

Many researchers have made use of correspondence and other records from the Papers of Professor Henri Hyvernat, a founding faculty member of The Catholic University of America and an early contributor to the collections that now comprise the University’s Semitics/ICOR Library. Less well known is an individual who was ever-present in the Professor’s life and worked closely with him for many years. Miss Amalia Steinhauser served as Hyvernat’s housekeeper while he resided near the University at 3405 12th St. NE in Brookland during the early years of CUA. Amalia’s story comes to life when one examines the years of extant correspondence (1910-1925) between her and Professor Hyvernat, now housed in The Catholic University of America Archives, part of Special Collections.

Amalia was born in Germany in 1868 to William and Maria Steinhauser, née Binig. Census records seem to suggest that Amalia and her younger sister Martha arrived in the United States sometime during the mid-1890s. It is possible that Amalia’s brother Cleophas, a member of the Franciscan order based in Egypt and fellow scholar in the field of Oriental Languages was the one to introduce her to Hyvernat. Because she was his housekeeper and friend, Professor Hyvernat came to know and care for the members of Amalia’s family. Amalia visited Martha and her family in Philadelphia on more than one occasion, and Martha’s children spent the summer of 1921 in Brookland. Although fluent in English, Amalia’s letters (especially her earlier ones) reveal a tendency toward a German pronunciation of certain words. She does not explicitly address whether this caused difficulties for her in the years following World War I, when anti-German sentiment in the United States was on the rise.

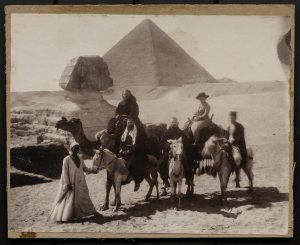

While some might assume that the role of housekeeper was a limiting one for Amalia, her position enabled her to travel to an extent that would have been uncommon for many women of her time. Letters written between Amalia and Hyvernat in 1912 illuminate some of Amalia’s experiences abroad. She visited various cities in the Middle East as well as Cairo in Egypt during this year, as well as several major cities in Western Europe before visiting friends in her native Germany and then back to the United States. She returned to Europe in 1923: her letters show that she traveled to Paris in the late summer and stayed there for significant amounts of time throughout the next two years. While Amalia organized travel arrangements for Hyvernat, the professor did the same for her as well: in 1925, he arranged for her lodgings with a group of Sisters during an anticipated upcoming visit to Rome. Amalia also had the opportunity to travel to other parts of the United States. She frequently inquired after the individuals traveling or working with Professor Hyvernat, assuring him of her prayers for their health and providing news related to their many mutual friends in Washington, D.C.

Certain acquaintances of Amalia appear frequently enough throughout her correspondence that they merit special consideration. One such person is Miss Antoinette Margot (1842-1925), a Catholic convert who arrived in Brookland after having served as a nurse alongside close friend Clara Barton, the well-known nurse who would go on to found the American Red Cross. Across the street from Professor Hyvernat’s residence on 12th St NE stands St. Anthony’s Catholic Church, a parish established in 1896 that would grow significantly during the years encompassing Hyvernat and Amalia’s correspondence. Hyvernat and Antoinette Margot were responsible for the founding and construction of this Church, which became a focal point of social life in Brookland during the years when Amalia and Professor Hyvernat resided on 12th Street. Amalia assured Hyvernat that she frequently looked in on their elderly neighbor, sometimes assisting her with household chores. Amalia herself was responsible for cleaning and obtaining household necessities; keeping track of finances; and overseeing the essential upkeep of the house, a task that included bringing coal to warm the house during the colder months of the year. She also took it upon herself to complete various improvement projects around the house.

Hyvernat remains such a deeply felt presence in the Semitics/ICOR Library because he donated many of the first items that became part of the Collection and contributed to some of the volumes that continue to be most widely used by students, visiting researchers, and others. Few are aware that other objects became part of the Semitics/ICOR Collection due to the generosity of Amalia. She not only donated items initially acquired by her brother Cleophas but also artifacts that she had selected herself (not necessarily for their scholarly significance). Accession records that reveal which items Amalia obtained provide some insight into her personal taste. For example, she obtained a medieval Arabic lamp from Nazareth while traveling in April 1912 and received a Byzantine lamp from the Benedictine Fathers of Jerusalem that Hyvernat later donated to the Museum. She also donated an elfstone from the Synagogue of Tiberius near Athens; specimens of mosaic from Jericho; and rolled pebbles from the Dead Sea. These records place Amalia as a donor along with the prominent scholars with whom Hyvernat continually corresponded: at one point she mentions speaking with Mrs. Dickens, a fellow contributor to the lamp collection in the Semitics/ICOR Library. In this way, Amalia’s passing references to these individuals in her letters become more than mere observations or polite questions related to their well-being. She was a donor in her own right, one who contributed to the rapid expansion of Catholic University Museum collections during the early years of the institution.

Amalia passed away in October of 1944 in Philadelphia after having lived there for about six months. She was buried in Most Holy Redeemer Cemetery in the city along with her other family members, and a service was held at St. Bonaventure’s Church. Amalia’s niece, Marie Baum, served as the executrix of Amalia’s will and made certain that designated funds were used to support the ICOR Library at a time of great transition after the death of Hyvernat three years earlier. It seems of deep significance that Amalia continually signed her letters to Hyvernat with the closing, “Your Humble Servant in Christ.” Perhaps nothing else taken from Amalia’s letters reveals more profoundly the way in which she perceived of herself and the work in which she was engaged for Father Hyvernat.