Our guest blogger is Julie Pramis, who is a graduate student in Library and Information Science (LIS) at the Catholic University of America.

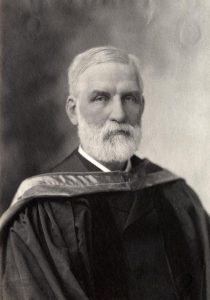

What more fitting collection for the university archives to have than one of Catholic University’s own founding members: William C. Robinson. Judge Robinson was a founder, professor, and dean of the Columbus School of Law, then known as The School of Social Sciences. After a 27-year long career as a law professor at Yale, he left his comfortable position to move to Washington, D.C. (somewhat reluctantly, due to health concerns: he was in his sixties at the time!) to ensure the founding of a law school at the university of his faith. His personal papers include a great collection of his correspondence with John Keane in their planning of the school, and many of his notes on the law for the courses he taught.

William Callyhan Robinson was born on July 26, 1834 in Norwich, Connecticut (Alumni Record of Wesleyan University, p. 421). Robinson was raised Methodist, but after graduating from Dartmouth he entered the General Theological Seminary, where he studied for the Episcopal Ministry. In 1857 he graduated from the Seminary and married his first wife, Anna Elizabeth Haviland. He became a missionary of a parish in Pittston, Pennsylvania, and then a rector in Scranton. In the early 1860s, Robinson converted to Catholicism and left his position as a clergyman. Had he not been married, Robinson likely would have become a Catholic priest.

In 1891, Bishop John Keane wrote to Judge Robinson about founding a school of social sciences at The Catholic University of America (Ahern, P. H., 1949, p. 98). Robinson had great interest in establishing a law school in CUA, as both a proud Catholic and long-serving practitioner and professor of the law. However, he was unsure what effects the climate of D.C. would have on his health, a man accustomed to the New Haven atmosphere. Moreover, he had a comfortable position at Yale—whose law school he helped bring back from the brink of extinction—and he was in his middle age at the time. Bishop Keane was persuasive, though, and Robinson was absolutely committed to the founding of the school. Later on, Robinson would write to a friend about the difficult work involved in bringing the School of Social Sciences into being, and stated that “The creation of a University is not the task of sinecures” (Jackson, F. H., 1951, p. 60). Robinson taught law at CUA until his death on November 6, 1911. He gave his last lecture on the Friday before his death.

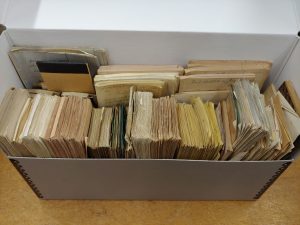

The Papers of William C. Robinson were interesting to process for this first-year Library and Information Science student. Sometime prior to the Fall semester of 2021, the papers had been sorted into acid-free folders, placed in Hollinger boxes, and a finding aid was started and then abandoned. Many small notebooks were left unfoldered and unsorted in their boxes. Additionally, some of the materials in the last boxes had sustained fire damage, which happened prior to donation to the archives. The larger of these items – three bound volumes – were wrapped in acid-free paper. Staples, pins, and paperclips were left in the papers. A group of extra-long papers that were folded in half remained as such.

I started my work with many questions and a general understanding of archival work. Why leave metal fasteners – susceptible to rust – in these papers that are more than 100 years old? Why leave these folded papers folded rather than flatten them to ease researcher use? How do I handle unsorted notebooks with no clear chronological order? What in the world do I do with fire damaged paper? Since then, I’ve learned a lot about MPLP: More Product, Less Process, as well as more about the competing needs of archivists’ resources and researcher’s needs. With this information I’ve learned to understand the previous processor’s work as though they were explaining it to me through time. With the papers stored in both acid-free folders and boxes, and stored in a climate-controlled environment in the university archives, rusting metal fasteners is less of a concern and would serve more to take time away from other, more necessary work in processing the collection. Unfolding papers that have been folded for such a long time and of such an age (more than 100 years at least), unfolding would require humidification and perhaps a professional conservator; concerns of time, money, and other resources means that we can leave the papers as they are. Those same concerns apply to various unsorted notebooks: the time and money involved in trying to sort items that may not have a clear order even after extended effort tells archivists that we can apply MPLP here, too. As for the fire damaged items, I had to approach that as its own beast.

Some items were loose papers singed on the sides; some items were large bound volumes singed on the edges, effectively sticking the pages together; and some were smaller notebooks with fire damage that did not stick the pages together as with the larger volumes. I researched what archivists and/or conservators could do to improve singed materials. Much of my research turned up what to do with recent fire damage, which in most situations would be followed by water damage from sprinklers, the fire department, or any other water-suppression system designed to stop the fire. These materials were damaged in 1977, in Judge Robinson’s personal library. His grandson, John B. Robinson, donated the items to The Catholic University of America with both party’s full knowledge of the state of the items. They are long dry. I had already re-foldered the loose papers from their manila envelopes into acid-free folders and boxes before I understood the MPLP process, and that the papers were probably fine in their envelopes. You live, you learn. The large bound volumes are still wrapped in the acid-free paper they were in when I found them.

Regardless, I am glad that I sorted some of these items into more Hollinger boxes. The last box, box 17, was a bit heavy and very full. Especially considering nearly all of these items had some level of fire damage, having all of them stacked on each other in a heavy banker’s box that may be troublesome for some to lift, I think sorting them out into three boxes (two Hollinger and the original banker’s box) will help to prevent unnecessary handling of the items. Boxes 17, 18, and 19 can be handled individually, so any use of box 17 won’t result in needing to move or rearrange items from 18 or 19 to ensure they all fit back in the box. Additionally, one non-damaged item in box 17 is Judge Robinson’s leather diploma case. It is a little worn with age, but no fire damage, and the contents inside are in good condition (rolled tightly, though, so handle with care!).

Working with Judge Robinson’s papers hands-on gave me so much more insight into archival accessioning, processing, and description and access than I could have had solely in the classroom. In the beginning of the semester, I was intimidated by the size of the collection and how much work I needed to do to sort through every paper. In hindsight, a 17-box collection is a good beginner’s introduction – not too big, not too small – and I know now that I don’t have to examine every piece of paper. Thinking about how to arrange the collection for future researchers felt like a lot of responsibility for a first-time processor. That’s why I am so grateful to the processor before me, who showed me through their actions and restraint what archival work we should prioritize first and what we can prioritize last, if we get to it. If I could change one thing now, I would have worked on the papers more slowly. Since I had the full semester to work on these papers, there was not as much of a time limit on completing the processing and creating the finding aid with EAD as there would be for a professional archivist. I’ve had the great opportunity to work in the archives at my pace focused entirely on one collection, which I understand now is not every archivist’s experience.

The papers themselves are fascinating, and available for further examination in the CUA archives! In addition to his work on founding CUA’s law school and other work in the law, you can find the work he did tracing his genealogy, personal and professional correspondence, and various financial and other papers accumulated in the course of his lifetime. Please take a look at Judge Robinson’s papers if you get the chance.

References

Ahern, P. H. 1916-1965. (1949). The Catholic University of America, 1887-1896; the rectorship of John J. Keane. Catholic University of America Press, 1948 [c1949].

Alumni Record of Wesleyan University, Middletown, Conn. (Third edition). (1883). Press of the Case, Lockwood & Brainard Company. https://books.google.com/books?id=gqMgAAAAMAAJ=PA421#v=onepage=false

Jackson, F. H. William C. Robinson and the Early Years of the Catholic University of America, 1 Cath. U. L. Rev. 58 (1951).

Thank you so much for your work!! It’s truly commendable and very meaningful to me as William C Robinson was my great grandfather. I can’t tell you how much the work you put into this means. I hope to someday visit the University and take a look at the archives in person.

Professor Robinson was my Great Great Grandfather. I have been doing research on his life and also my Great Grandfather, George W. Robinson who was a lawyer and Judge in CT, graduating from Yale. He also has archives, including diaries from him and my Great Great Grandmother, Anna Elizabeth Haviland Robinson at Yale University. Very interesting Man! Thank you for your research!