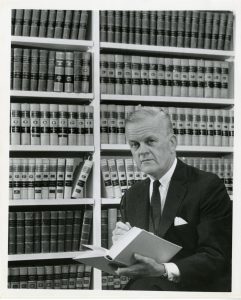

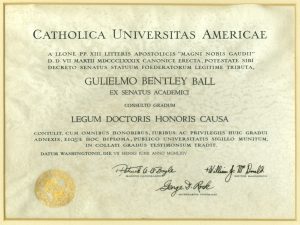

William Bentley Ball (1916-1999), subject of a previous blog post and whose papers reside at Catholic University, was a Pennsylvania based constitutional lawyer and devout Roman Catholic, dubbed “God’s Litigator” and “Religious Freedom Fighter” by the Catholic Press (1). Ball argued nine cases and advised on more than two dozen others, primarily related to religious freedom and the First Amendment, before the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS). Ball was also an artist, poet, and author.

As a young man, Ball was a devout Catholic, anti-New Deal activist, and U.S. naval officer in World War II. After the war, he studied law at the University of Notre Dame, taught at Villanova, and served as general counsel for the Pennsylvania Catholic Conference. His first case before SCOTUS was in 1967 when he entered a brief on behalf of U.S. Catholic bishops supporting the overturn of prohibits on interracial marriage in the celebrated Loving v. Virginia case. Ball achieved national attention with the 1972 Wisconsin v. Yoder case in which that state tried to force Amish children to attend high school when the latter’s belief system found that unnecessary. Ball represented the family in question, the Yoders, pro-bono, arguing before SCOTUS that this prevented defendants from performing their religious obligation, and the justices agreed 7-2.

Ball’s other most famous case was in 1993 with Zobrest v. Catalina Foothills School District in Arizona. James Zobrest (b. 1974) and his family were Pennsylvania transplants and Catholics who had moved to Arizona seeking the best possible education for the hearing impaired. Although many in the Deaf Community favor separate schooling, the Zobrests sought to mainstream their son, which required a daily on site sign language interpreter in the school to facilitate young James’ communication and learning. Public funding of these interpreters was not a problem so long as James attended public schools but when he transferred to a Catholic High School, Salpointe in Tuscon, said funding was denied by the Catalina Foothills School District, believing that it was a violation of the First Amendment’s establishment clause, which generally prohibits the government from establishing, advancing, or giving favor to any religion. Arguing this was religious discrimination, the Zobrest family went to court.

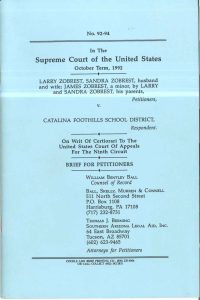

The federal district court in Arizona held that furnishing a sign-language interpreter violated the First Amendment the interpreter would via sign language promote James’ religious doctrine at government expense. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the lower court’s decision, stating that the interpreter would have been the instrumentality conveying the religious message with the local school board, in effect, sponsoring the religious school’s activities. The court admitted that denying the interpreter placed a burden on the parents’ right to free exercise of religion, but it was justified to ensure that the First Amendment was not violated. The Zobrests engaged the services of the progressive Arizona Center for Law in the Public Interest. Their lawyer, Thomas Berning, teamed up with the Conservative Catholic litigator, Ball, the latter working again on a pro bono basis, to take the case to SCOTUS. Incidentally, Ball’s daughter had been young Jim Zobrest’s first sign language interpreter before the family had left Pennsylvania. In their landmark case, Ball and Berning were supported by the Department of Justice on the basis of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), The Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights, the Latter-Day Saints (Mormons), Missouri Synod Lutherans, Southern Baptist Convention, National Council of Churches of Christ, and the National Association of Evangelicals. In opposition, were the ACLU, Americans United for Separation of Church and State, the American Jewish Committee, and the Anti-Defamation League (2).

On February 24, 1993, the case was held before the Supreme Court. Ball argued that the school district’s refusal was a violation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, as well as the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment. Chief Justice William Rehnquist authored the majority’s 5-4 opinion, ruling that the service of a sign-language interpreter in was part of a government program distributing benefits neutrally to disabled children under the IDEA regardless of whether the school was public, private, or religious. Rehnquist further held that the only economic benefit the religious school might have received would have been indirect and that aiding the student and his parents did not amount to a direct subsidy of the religious school because the student, not the school, was the primary beneficiary. The Supreme Court thus ruled that there was no violation of the establishment clause, and the decision of the Ninth Circuit was reversed. Zobrest vs. Catalina is a significant case because it marked a shift in the court toward interpreting the establishment clause to allow government-paid services for students who attend religiously affiliate nonpublic schools and was notably followed by Agostini v. Felton (1997), in which the court held that remedial services financed by federal funds under Title I could be provided in parochial schools.

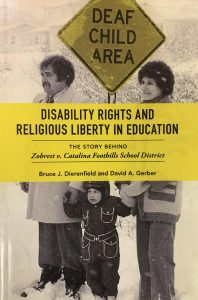

Although Jim had graduated before the SCOTUS decision the family was nevertheless compensated for the thousands of dollars a year they had scraped together for his sign interpreters. For Ball, this was perhaps his finest victory in the twilight of his notable career. The definitive account of this notable piece of legal history is Bruce J. Dierenfield and David A. Gerber. Disability Rights and Religious Liberty in Education: The Story Behind Zobrest v. Catalina Foothills School District. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2020. Much of the source material is available in the aforementioned papers of William Bentley Ball at Catholic U. For access questions, please contact us at lib-archives@cu.edu.

Endnotes:

(1) Bruce J. Dierenfield and David A. Gerber. Disability Rights and Religious Liberty in Education: The Story Behind Zobrest v. Catalina Foothills School District. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2020, p. 104.

(2) Ibid, pp. 131-132.

(3) Thanks to HK for her assistance.