Wandering through the Rare Books stacks is always an adventure. The shelves hold all kinds of secrets, waiting for the right librarian to pull them, or the right researcher to request them. But on a rainy October afternoon, with Halloween on the mind, it is the witchcraft books that stand out to me.

The Rare Books selection of witchcraft volumes covers a wide range of fascinating topics: prophecy, astrology, somnambulism (which according to many of these volumes has some fairly magical connotations), and general folklore. If you’re having trouble with local witches tormenting you, Witches and the Second Sight in the Scottish Highlands, by John G. Campbell, published in 1902 may be able to offer you some relief. This book contains a near limitless selection of scenarios in which unsuspecting innocents might find themselves plagued by witches, and several practical solutions for ridding yourself of their evils. For instance, in the event that a witch is turning herself into a white hare and stealing your cow’s milk in the night (Don’t worry, it can happen to anyone), you need only put a bit of silver in your gun (a sixpence will work, or a silver button if you don’t have any obsolete currency on hand) before shooting at the hare. Naturally the silver is essential, for if you should forget to include it, the witch can easily use her powers to turn your weapon against you and you may find your gun exploding violently in your hand. Sound advice, and perhaps it’s better to follow the age-old ‘better safe than sorry’ and refrain from shooting at any hares unless you have silver in hand. Just in case.

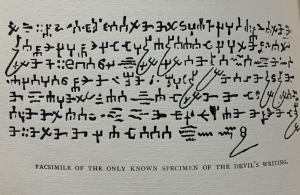

Our next book, first published in 1896, is ominously titled The Devil in Britain and America and written by John Ashton on the grounds that “all modern English books on the Devil and his works are unsatisfactory.” He goes on to complain that most books redundantly cite the same examples of witchcraft and that, perhaps most importantly of all, “not one of them is illustrated.” Given this mission statement, it must come at no surprise that Ashton’s book is absolutely teeming with surreal little engravings with witches and devils, the odd and the obscene. The stories themselves come from all manner of sources, as Ashton proudly notes in his preface. (No ‘oft-repeated cases’ for him!) The material can range from an analytic (such as the word can be used in this situation) account of how witches are made, to a mid-seventeenth century English satirical ballad meant to demonstrate the devil as “sadly deficient in brains,” entitled, The Politic Wife or, The Devil Outwitted by a Woman, where one hapless man meets the devil (who introduces himself as ‘Dumkin the Devil.’) and is saved by his wife’s quick thinking. The book also contains what it claims to be the only known sample of the devil’s writing.

So far these books can be easily identified as the sort of things created for people who enjoy delighting in the taboo and the occult, stories meant to entertain and to thrill. Certainly there was an audience for them. The next work we’ll be looking at was actually given as a Christmas gift in 1930, so its handwritten inscription tells us. Ghost stories as Christmas gifts were not an uncommon tradition, especially in the Victorian era (think Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.) This one seems ideal for reading aloud around a fire on Christmas eve. It’s a slim little pamphlet, (coming in at 7 pages, and that includes its paper cover) printed in 1928 and entitled The Story of Mr John Bourne. It tells of how the titular character was made the manager of an estate, and how when he was near death, the chest which held the details to that estate rose and unlocked itself, only to relock itself again upon his death, so that try as they might, no one could ever open it there after. Certainly it’s an uncanny little story, but I don’t know that it’s something I would traditionally associate with witchcraft, were it not for the “abracadabra” slowly vanishing down the title page. So why shelve it amongst all these other definitely witchy books?

As it turns out, The Story of Mr John Bourne is actually an excerpt from a much larger work, bearing the self explanatory and rather lengthy title, Saducismus triumphatus, or, Full and plain evidence concerning witches and apparitions in two parts : the first treating of their possibility, the second of their real existence / by Joseph Glanvil. With a letter of Dr. Henry More on the same subject and an authentick but wonderful story of certain Swedish witches done into English by Anth. Horneck. Although the excerpt of this work as we have it preserved seemed intended more to cause fearful delight, much like the books we were just discussing, the purpose of the larger text was much less recreational and its effects far more terrifying. Joseph Glanvill was an English preacher and philosopher, who believed that without the threat of demons and witches, people would see no reason for religion. In fact, he went so far as to view a lack of belief in the supernatural as akin to atheism. The book, which sought to prove the assured existence of witches, was hugely popular, and thought to be an influence on religious leaders such as Cotton Mather, a New England preacher known for stirring up witchcraft hysteria during the Salem witch trials.

In fact, if you’re interested in putting Saducismus Triumphatus in the historical context of Cotton Mather and the Salem witch trials, our library also contains his account of some of the witch trials he attended as well as a defense of the guilty verdicts given to those accused. It appears in a book called Salem witchcraft: comprising More wonders of the invisible world, collected by Robert Calef; and Wonders of the invisible world, by Cotton Mather; together with notes and explanations edited by Samuel Fowler, a man who served as a member of the Massachusetts Constitutional Convention in 1853, as well as being known for his collection of books on witchcraft and American history which far surpasses our own modest assortment. The book juxtaposed Mather’s account with the first publication to ever publicly condemn the trials. Written by Robert Calef, the essay is in direct response to Mather’s and attacks both the injustice of the trials, and Mather’s own part in it.

Salem witchcraft is not the only book in our Special Collections on the topic of the Salem witch trials, and perhaps it is not unsurprising that this tragedy has captured the fascination of so many people for so long. As general opinion on witchcraft shifted, it seemed strange (macabre, even) that the contents of stories you read for thrills or give as Christmas gifts were once accusation enough to earn a death sentence. Regardless, the Special Collections witchcraft section represents the long standing fascination with witchcraft that has captured peoples’ imaginations for centuries, for better or for worse.