It is difficult for the twenty-first century mind to grasp the endless drudgery of the daily lives of nineteenth century workers, especially the masses of the poor, and particularly women. While the status of mother or wife was better than that of domestic servant, there was little else separating them from the constant toil of hauling and fetching, cooking and cleaning, child and elder care. Additionally, unmarried or widowed women worked in factories and other places of commercial employment with harsh conditions, low pay, and scant regard. Out of this challenging milieu arose the example of Lenora Barry, called ‘Labor’s True Woman.’ Born on August 13, 1849, in County Cork, Ireland, as Leonora M. Kearny, daughter of John Kearny and Honor Granger, she was the only woman to hold national office with the Knights of Labor, America’s first large and somewhat successful labor union during their brief heyday in the mid to late 1880s. She was a dedicated advocate for bettering the conditions of American working women and the progress of women’s rights, including suffrage, during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era.

Her Irish farming family immigrated in the wake of the Irish Famine to Pierrepont, a rural New York community, in 1852. Following her mother’s death in 1864, her father remarried to a woman barely Leonora’s senior, with the resulting tension prompting the younger woman to attend a teaching school. After receiving a teaching certificate at only age 16, she taught at a local school for several years. She married Irish immigrant William E. Barry, who was both painter and musician, in 1871 and they settled in Potsdam, New York, where their first child, a daughter, was born in 1873. Per state law and despite a chronic teacher shortage, she was forced to give up teaching because she was a married woman and forced by economic necessity into manual labor. She and her family moved constantly, with two sons born by 1880 when her husband and daughter both died. After years as a seamstress, she found work in an Amsterdam, New York, hosiery factory where she and fellow workers faced hard conditions, low pay, and long hours.

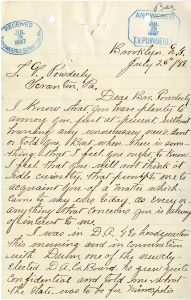

In order to take positive action on the issues faced by her fellow workers, Barry joined the women’s branch of the Knights of Labor in 1885, near the time of that organization’s zenith. Originally a secret postwar group of Philadelphia clothes workers, it was transformed into an association fighting for labor reform across trades and industries on a national level. Barry soon rose to become master workman or president of her local Knights branch of about 1,500 members, then head of District Assembly 65, which had fifty two local branches with over 9,000 members. The following year she served as one of five district delegates to the General Assembly of the Knights of Labor in Richmond, Virginia. Endorsed by the Knights national leader, Terence V. Powderly, whose archival papers hold pride of place in Catholic U’s Special Collections, Barry was voted by the convention delegates to lead the newly created Department of Women’s Work. She was the first woman to be paid as a labor organizer and the only one to hold national office in the Knights of Labor. Her charge was to investigate women’s employment conditions, build new Knights assemblies, agitate for equal pay.

Barry travelled across the country investigating the lot of women workers, and her reports to the Knights General Assembly in 1887, 1888, and 1889 detailed abuse of both women and children. She also gave over 500 speeches during her career, with ‘The Dignity of Labor’ on July 4, 1888, in Rockford, Illinois, being long remembered. Nearly 65,000 women belonged to the Knights, who offered jobs and affordable goods as well as supporting boycotts in women workers’ interests. About 400 Knights locals included women but Barry found it difficult to build a strong following due to both apathy and divisions trying to organize women in a male dominated society. Employers denied her entrance to their work sites and better paid workers hesitated to join labor movements fearing their situations would decline. Barry began to support state and federal legislation to protect workers, with a notable success in Pennsylvania passing its first factory inspection act in 1889.

Unfortunately, for both Barry and women workers, she became embroiled in internal disputes with Knights Secretary-Treasurer, John Hayes, who took control of the Women’s Department in 1888 and harassed Barry with tacit support from Powderly to her resignation in 1890, effectively ending the Women’s Department. Another factor though was her marriage to Obadiah Read Lake, a St. Louis printer and telegraph editor, that same year and her notion that women should not work outside the home unless there was economic need. Barry continued to travel and agitate for women’s suffrage and temperance, though not ignoring labor as she spoke to the Congress of Women at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Later in life, known as ‘Mother Lake,’ she moved to Minooka, Illinois, and was active in both the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and Catholic Total Abstinence Union. Perhaps ironically, she died July 18, 1923 due to mouth cancer. While there are no papers of her own at Catholic University’s Special Collections, her correspondence and reports feature prominently in the those of Terence V. Powderly and John W. Hayes, which can also be accessed digitally via ProQuest’s History Vault. For more on the Knights and/or women workers of the era, see the scholarship of Susan Levine, Steven Parfitt, Kim Voss, and Robert Weir.