This week’s post is guest authored by Marielle Gage, a CUA graduate student in History.

“My, how times have changed!”

Who hasn’t heard some variety of that phrase, if perhaps not in as stilted, “proper” phrasing as above? It’s often an overwrought sentiment, immediately followed by a “when I was your age…” or nostalgia of times past (that everyone complained about at the time) now seen through golden lenses. But in some cases, the sentiment is more than fair.

Take, for example, television. A hundred years ago, no one owned a television. Even thirty years later, during World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt relied on the radio, not television, to broadcast his “fireside chats” to the nation. And ten years after that, there were three regular channels broadcasting, one of which had no problem dedicating four Sunday afternoons to opera in the summer of 1959.

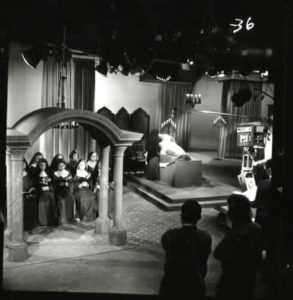

That’s right. The same year the Grammy Awards were first broadcasted on NBC, that same station approved the broadcasting of four one-act operas, written by and starring CUA faculty, students, and alumni, at 12:30 pm on each of the four Sundays of May. The impetus wasn’t from the higher-ups within the National Broadcasting Channel, but rather from the National Council of Catholic Men, who had a partnership with NBC to broadcast, on radio and on television, a weekly “Catholic Hour” in which presenters could explain, examine, or defend the Catholic faith. CUA’s own Fulton J. Sheen was a frequent participate in the broadcasts; he and others would expound on themes such as the Virgin Mary, racism, the last words of Christ, labor, or marriage. Perhaps wishing to change up the formula, the NCCM commissioned the four one-act operas from CUA’s music department faculty in late 1958. While a couple of different themes were suggested (the early correspondence hints frequently of a retelling of Guadalupe, but is frustratingly vague on any details, and the idea was later dropped), the final four operas were: Dolcedo, the last day of an atheistic philosopher now in the care of nuns (music by Emerson Meyers, libretto by Dominic Rover, O.P.); The Cage, the story of an elevator operator who desperately wishes to travel, but feels trapped caring for his invalid and verbally abusive mother (music by George Thaddeus Jones, libretto by Leo Brady); The Decorator, a glimpse into the life of a middle-class mother trying so hard to be fashionable (music by Russell Woollen, libretto by Frank and Dorothy Getlein); and The Juggler, a retelling of the “clown of God” legend (music by William Graves, libretto by Arch Lustberg).

While none of the operas, perhaps, are must-see classics (The Decorator, in particular, is a bit heavy-handed), it still must have been an adventure for the CUA students who participated and watched the productions. Unfortunately, little remains of any publicity or retrospectives within the CUA community concerning the operas. The surviving letters and photographs, then, remain a tantalizing glimpse at a curious moment in CUA’s musical history, and of American cultural history in general, from a time when it was not inconceivable that a portion of the American population would choose to spend their Sunday afternoons watching opera.