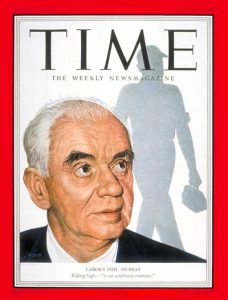

In 1904, a young coal miner in western Pennsylvania, terminated for fighting with his boss over fraudulent practices, was also evicted from his home and forced to leave town. He sadly observed the workingman “is alone. He has no organization to defend him. He has nowhere to go.”¹ Thereafter, this Catholic immigrant from Scotland, Philip Murray (1886-1952), devoted his life to unionism, becoming one of the most important labor leaders in twentieth century America. He served as Vice President of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), 1920-1942; second President of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), 1940-1952; and first President of the United Steel Workers of America (USWA), 1942-1952. He worked to form an alliance between industrial unions and the Democratic Party as well as smoothing relations with the older American Federation of Labor (AFL) leading to the merger of the AFL and CIO in 1955. He was also active in supporting civil rights and standing against Communism.

Murray was born May 25, 1886 in Blantyre, Scotland, to Irish immigrants William Murray and Rose Ann Layden. His father was a coal miner and his mother a weaver in a cotton mill who died when Murray was only aged two. His father soon remarried, to a Scottish woman, having eight children with her. Young Murray joined his father in the Scottish mines at age ten and went to union meetings with him. In 1902, they immigrated to the mining town of Irwin, near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Following the travails mentioned above, Murray was elected President of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) local in Horning in 1905, becoming a member of the UMWA’s International Board in 1912, President of District 5 covering western Pennsylvania in 1916, and International Vice President in 1920. An effective negotiator, he worked closely and loyally with UMWA President John L. Lewis through two difficult decades.

After the New Deal began in 1933, Murray successfully reorganized the UMWA and increased membership under federal legislation enabling collective bargaining. His vision of social justice derived from his family union tradition and Catholic faith, in line with papal encyclicals on the rights and responsibilities of both employers and workers. Murray was also Chairman of the Steel Workers’ Organizing Committee (SWOC), 1936-1942, and its successor, the United Steelworkers of America (USA), 1942-1952. After repudiating Franklin Roosevelt in the 1940 election, Lewis retired as President of the CIO, replaced by Murray, who promoted labor cooperation during the Second World War and supported Roosevelt’s reelection in 1944. In retaliation and after a bitter struggle, Lewis removed Murray as UMWA Vice President in 1942.

Murray was a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and directed the CIO to establish a Committee to Abolish Racial Discrimination. After the war, he opposed the Taft-Hartley Act that eliminated the closed shop and controversially expelled Communists from the CIO.² He married Elizabeth Lavery in 1910 and they had an adopted son. A naturalized American citizen since 1911 Murray nevertheless spoke with a Scottish accent and often wore a kilt. He died November 9, 1952 in San Francisco and is buried in Saint Anne’s Cemetery in the Pittsburgh suburb of Castle Shannon. A biographer observed Murray never “sought the spotlight and yet his contribution to the welfare of the unionized workers was great.”³ Catholic University houses the Philip Murray Papers, which includes a digitized photograph series, along with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) Records, while additional related collections are at Pennsylvania State University (PSU) and the Indiana University of Pennsylvania (IUP).

¹Ronald W. Schatz. ‘Philip Murray and the Subordination of the Industrial Unions to the United States Government,’ Labor Leaders in America. Melvyn Dubofsky and Warren Van Tine (eds) Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1987, p. 236.

²Steven Rosswurm (ed.) The CIO’s Left-Led Unions. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1992.

³Juanita Ollie Duffay Tate. The Forgotten Labor Leader and Long Time Civil-Rights Advocate-Philip Murray. Greensboro, North Carolina: North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University Press, 1974, p. xi.

I went to the Philip Murray Elementary School in Chicago for a couple of years shortly after it opened in the 1950s. At last I know who it was named for! Thanks! (I saw your posting on H-Pennsylvania)

Murray’s war against real and imagined communists in the CIO produced disastrous divisions in American labor and facilitated the encouragement of rightist personalities and ideas in the culture at large. His under-the-table aid to the destructive dissident Jim Carey among electrical manufacturing workers should, in itself, give pause to those who praise Murray.