The following post was authored by Graduate Library Professional Juan-Pablo Gonzalez.

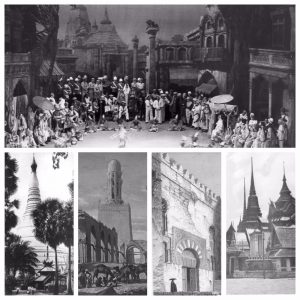

Joseph Novak was The Chief Scenic Artist of The Metropolitan Opera Company in New York City, from 1910 to 1952—an approximately 40-year tenure. His archival papers consist of a collection of artistic works and associated documents that were originally donated to The Catholic University of America’s School of Music to become a part of the Luce Library in 1976; however, the collection was housed, processed, and exhibited at the Mullen Library. The collection consists of approximately 500 sets of opera models, 100 photographs, 600 drawings, uncounted numbers of clippings, and associated documents produced by Novak. Among the many intriguing projects undertaken by Novak was his set and costume design for the 1932 revival of Lakmé —a tale of the Orient…

Embodiment: Becoming the Spectacle of the Opera.

In 2013, Gerard-Georges Lemaire wrote a compendium titled Orientalism: The Orient in Western Art. He opens the monograph with a meditative preface by Genevieve Lacambre who ponders: “Where exactly was the Orient that was so vividly depicted by the Orientalists?…we ought more accurately speak of the Orients”—a place of multiple iterations. The Orient is difficult to define because of the supernumerary of cultures that were swept up by Europe’s non-stop quest to capture the ontological essence of The East and to become the author of its authenticity. The Orient was an imaginative state, channeled by nearly the whole of Western society, across an astonishing temporal reach, in which “For over two thousand years the Orient has exercised an irresistible fascination over Western minds…” The Orient meant different things to different Western cultures and within each respective culture there was a great deal of intra-cultural variegation as to who and what were referred to as Oriental.

Orientalist art was the materialization of the push and pull between a Europe that was arrested by its profound fascination with the other and a Europe whose cultural mythos had set it diametric to the vast array of cultures that comprised world around it. These opposing energies engendered the desire to recreate other cultures through the visual arts and imposed a layer of cultural semantics through the establishment of a visual vernacular that was steeped in decadence and violence.

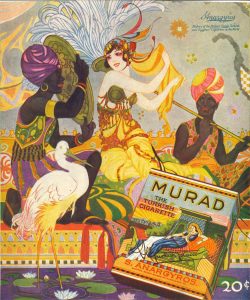

The orient was conjured by those who had visited the regions that unwillingly carried the pseudonymous “Orient” moniker and was remixed by those who had never visited beyond the borders of Europe. By the 19th century, Orientalist art entered a grotesque stage—a semiotic shift that arose in response to new geopolitical occurrences. European’s Colonial expansion had created a new impetus through which “Some of the first nineteenth-century Orientalist paintings were intended as propaganda in support of French imperialism, depicting the East as a place of backwardness, lawlessness, or barbarism enlightened and tamed by French rule.” The striking paradox of the French artist’s use of the Orientalist genre to create sociological delimitation, was that Europe’s obsession with the Orient had driven its artists into a memetic state, wherein Europe began to see itself as the embodiment of The East: the owner of its peoples, its lands, and its luxuries.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art notes that “Male artists relied largely on hearsay and imagination, populating opulently decorated interiors with luxuriant odalisques, or female slaves or concubines (many with Western features)…” It was quite a twist, as Europeanized women began to appear as subjects in Orientalist works that were less about the patriarchal exercise of choreographing women’s sexuality and more about the prismatic renderings of whiteness and the subjugation of dark skinned persons. Whiteness had become an actor on the Orientalist stage, signifying a shift in the political attitude towards The East—from one of fascination, to one of possession and control. Darker skinned women began to be depicted as naturally born to please the European subjects in such works as the blandly titled Works Odalisque and Slave.

The desire to subvert other cultures while simultaneously consuming their artistic, intellectual, and cultural capital, in what The Metropolitan Art Museum notes as “…architectural motifs, furniture, decorative arts, and textiles, which were increasingly sought after by a European elite”, is the precarious intersection at which Joseph Novak undertook the task of creating the world of Lakmé —an operatic revival of the story of an Indian woman who viciously gives her life—and by extension her nation—in the name of Britain, embodied as a solider. According to Lakmé ’s father, the British solder is an oppressor who must be expelled from the native lands; however, the fantasy transfigures British oppression by dressing it in drag and having it masquerade as a mechanism that can grant Lakmé love, freedom, and power.

How did Novak imagine an Orient that would match the gravity of the vocal, symphonic, and narrative spectacles of the operatic stage? Not only would Novak need to imagine an already imaginary world, he would have to play upon these contortions to manufacture the woman who would inhabit it—the singer Lilly Pons, a European woman, would have to become the fantasy, of the fantasy, of the fantasy– a perpetual, indefatigable figure who was without a past and without a future. A mythical other—embedded in a tortuous hierarchy of somatic servitude but blissfully trapped in her prison of sensuality, luxury, and the desires of Western men for her.

Enter the World of Lakmé…

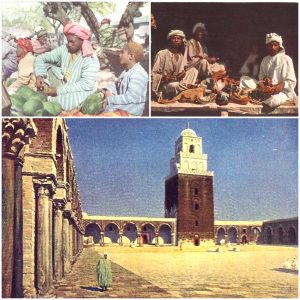

Click here to see a Pons performing The Bell Song from Lakmé, as was featured in the 1935 movie “I dream too much.” Apart from Pon’s brilliant Coloratura performance, in which she gave the audience everlasting life, the finalized Lakmé set can be seen, as well as, extras donning clothing that appears to be a fusion of Moorish and South Asian, as is consistent with Novak’s visual studies of North Africa, Moorish, South Asian, and South East Asian peoples’ textiles.