The novel coronavirus pandemic has left record numbers of Americans jobless—inviting comparisons between now and the Great Depression almost one hundred years ago. The Archives at the Catholic University of America (CatholicU) is well positioned to offer a historical perspective on current events. Two particular collecting strengths from the Depression era, relating to Catholic views on government and entertainment, crisscross the economics and culture of the period—and resonate in our own day.

Following the stock market crash of October 1929, the United States plummeted into an economic depression from which it would not fully recover until the onset of World War II. In 1933, unemployment peaked at 24.9% and Franklin Delano Roosevelt assumed the office of the president. In 1935, he signed the Social Security Act—introducing among other things the unemployment insurance program from which some 40 million Americans are currently seeking relief in the wake of “the unprecedented wave of layoffs” triggered by the pandemic. On the morning of Friday, June 19, 2020, The New York Times reported that, for the thirteenth week in a row, more than one million unemployment claims were filed.

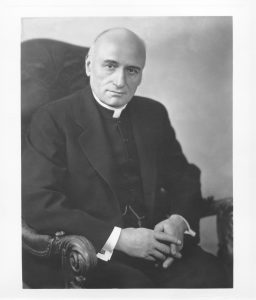

The American Catholic History Research Center and University Archives holds the papers of several Catholic supporters of FDR’s New Deal programs, including Patrick Henry Callahan, Francis Joseph Haas, John O’Grady, and John A. Ryan—who was nicknamed “Right Reverend New Dealer.” The digital exhibit Catholics and Social Security recounts the active role that Catholic Charities played in shaping New Deal legislation and the Social Security Act in particular. Importantly, though, the CatholicU Archives also document the activities of Catholic detractors of the New Deal—most notably Charles Coughlin. The Social Justice Collection consists of the weekly publication of the National Union for Social Justice (N.U.S.J.), which served as Coughlin’s political vehicle. Another digital exhibit, Catholics and Politics: Charles Coughlin, John Ryan, and the 1936 Presidential Campaign, details the conflicting views of the two Catholic priests on FDR’s (first) reelection campaign.

Meanwhile, against the backdrop of the worst economic crisis in U. S. history dawned the Golden Age of Hollywood. The fact that moviegoing actually spiked during the Depression has been cited amidst other financial meltdowns: during the Great Recession of 2008, for instance. The phenomenon is commonly rationalized in one of two ways: escapism or catharsis. No doubt entertainment has served similar ends during the COVID-19 pandemic, but it has found a new mode of delivery—skipping theaters altogether. After a long spring of streaming from the safety of the sofa, will the appetite for the big screen return?

Back in 1933, as the popularity of moviegoing grew, the church hierarchy’s concerns—mostly about the portrayal of sexuality and crime (especially the glorification of gangsters)—also grew. In response, the church founded the Legion of Decency. The Legion was ultimately subsumed into the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) Communications Department/Office of Film and Broadcasting (OFB), for which the CatholicU Archives serves as the official repository. The OFB records include about 150 boxes of film reviews and ratings for movies released from the 1930s onward.

One such movie has recently come back under scrutiny: Gone with the Wind (1939). The highest-grossing movie of all time, the star-studded epic set in the American South has routinely been criticized for perpetuating harmful stereotypes of Blacks. Heeding calls for racial justice incited by the murder of George Floyd, the subscription streaming service HBO Max temporarily took down the controversial classic in June 2020.

Gone with the Wind happens to be historically important to the Legion of Decency. When it was re-released in 1967 (having been reformatted from the standard 35mm into the wider 70mm film stock), it became the first movie for which the Legion (then known as the National Catholic Office for Motion Pictures, or NCOMP) changed its rating “without any alterations in the motion picture” [1]. For this, the President and CEO of MGM was “particularly grateful”; he welcomed the new A-II rating (morally unobjectionable for adults and adolescents) and jumped to the conclusion that “the cloud around this classic has been removed” [2].

Upon its release in 1939, Gone with the Wind had been rated B (morally objectionable in part, for all). The Legion’s objections: “The low moral character, principles[,] and behavior of the main figures as depicted in the film; suggestive implications; [and] the attractive portrayal of the immoral character of a supporting role in the story [which is to say, the prostitute]” [3]. Referring to the original objections—including “the famous use of the word “Damn” by Mr. Gable”—one Catholic reviewer wrote, “By the standards of 1967, these elements are rather harmless” [4]. But other elements not originally objected to had since (at the height of the Civil Rights Movement) become top-of-mind, as they have again today [5]:

One moral factor however which must be considered which did not seem quite so obvious years ago is the attitude of the film toward the South, slavery, and the negro. […] The slaves are presented as being content with their lot. […]

This is a ridiculous and immoral attitude, and not fair—we are shown the plantations but not the slave quarters. […] In view of this I recommend the Office reclassify the film AIII, for Adults, and that some observation be made on our attitude toward the treatment of the Negro in the film.

For more about Catholics and the Great Depression, please see the newly-launched research guide: Special Collections — Great Depression Resources.

Notes

[1] “NCOMP Upgrades Rating of ‘Gone With The Wind’,” Times Review, LaCrosse, Wis., September 15, 1967. OFB Reviews, Collection 10, Box 51, Folder 55.

[2] Letter from Robert H. O’Brien to Father Patrick J. Sullivan, September 1, 1967. OFB Reviews, Collection 10, Box 51, Folder 55.

[3] Letter from Mrs. Eva Houlihan, Secretary to Right Reverend Monsignor Thomas Little of the Legion of Decency, to Reverend Hilary Ottensmeyer, O.S.B., November 13, 1964. OFB Reviews, Collection 10, Box 51, Folder 55.

[4] and [5] “Gone with the Wind: Screened-Friday, May 5, 1967,” Rev. Louis I. Newman. OFB Reviews, Collection 10, Box 51, Folder 55.

Excellent blog. Interesting perspective on Catholicism of the era providing a comparison of the impact of the depression with our current crisis.