As a student you may be familiar with the term, Open Educational Resources. Yet, it can be difficult to grasp the full breadth of the Open Educational Resources conversation. So what are Open Educational Resources and how can we use them with proper attribution?

UNESCO defines Open Educational Resources (OER) as “teaching, learning or research materials that are in the public domain or released with intellectual property licenses that facilitate the free use, adaptation and distribution of resources.” OER differs from resources published under traditional copyright by allowing for much more flexibility in how the resource is retrieved and used. OER can come in a variety of formats including traditional textbooks or articles, videos and images, and even lesson plans or online courses. Essentially, OER are materials that are openly and freely available for use or re-use.

The cost-free nature of OER contributes to a more accessible and equitable academic environment. Using OER significantly reduces the cost of class materials for students and instructors alike. OER is also often distributed faster than resources that go through the formal publishing process. When researching a current topic, OER resources can often be a good source of timely information. When using less traditional OER, such as lesson plans or other course materials, OER allows for more flexibility and creativity in how a course is prepared, taught, and received. OER supports different learning styles as materials can be found in a variety of formats. And if a format is not available, the source content can be remixed and redesigned into something new due to the open nature of OER.

OER and the ‘Five Rs’

As a student, you may have previously used OER in your research, projects, or presentations. For example, you may have cited an open article in a research paper. Or maybe a professor of yours used an open textbook in your course. Maybe you’ve seen a classmate use open media in a presentation such as an image or audio licensed in the Creative Commons. All of these are great examples of how OER can be integrated into your current learning and academic life. Yet, before using OER, it is important to know about the permissions associated with the content. While all OER is ‘open’, some resources have more flexibility than others.

Most OER allows for some, or all, of the following permissions, known as the ‘Five Rs’ developed by David Wiley:

- Retain – make, own, and control a copy of the resource (e.g. download and keep your own copy)

- Revise – edit, adapt, and modify your copy of the resource (e.g., translate into another language)

- Remix – combine your original or revised copy of the resource with other existing material to create something (e.g., make a mashup)

- Reuse – use your original, revised, or remixed copy of the resource publicly (e.g., on a website, in a presentation, in a class)

- Redistribute – share copies of your original, revised, or remixed copy of the resource with others (e.g., post a copy online or give one to a friend)

The license deed of each resource will provide information on the permissions you have when using the resource. When using an OER in your work, make sure you know what permissions the resource allows.

Showing Proper Attribution: The TASL Method

When working with OER you may use an attribution statement, which gives credit to the author and source. Yet, note that attribution statements are not the same as citations. Attributions are not academic and should not be used in place of a citation in a scholarly work. Attribution statements are a more informal method that gives credit to the author/source materials, whereas citations are a formal scholarly practice. If formally citing an OER resource for a paper or other academic work, refer to your field’s style manual such as MLA, Chicago, or APA for citation rules. Attributions should be used to provide credit when a formal citation is not required, for example, when using a Creative Commons image in a blog post.

A helpful acronym for creating attribution statements is TASL. An ideal attribution includes all four components of TASL.

T = Title – what is the name of the resource?

A = Author – who created the resource?

S = Source – where can I find it?

L = License – how can I use it?

To properly attribute a resource, include the title, author and license with appropriate hyperlinks. Not all attribution statements will include all of this information. When creating an attribution, reasonable effort should be made to supply relevant information, yet attributions can still be valid without all of this information.

This attribution format applies to all types of OER, including textbooks. This open textbook, Legal Issues in Libraries and Archives, would have the following attribution: Legal Issues in Libraries and Archives by Ruth Dukelow and Michael Robak is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. This attribution statement was sourced directly from the resource. Oftentimes OER creators include attribution statements within their resource to make attribution easier. A good practice when using OER is to look for author supplied attribution statements.

Build Your Own Attribution

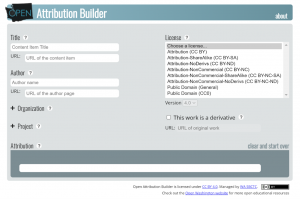

If you don’t prefer the TASL method or cannot find an author supplied statement, tools like the Open Attribution Builder, can assist when creating attribution statements. Plug in the information you have about the resource being used and the tool will create a statement for you.

For further details about attribution statements, visit the Best Practices for Attribution page on the Creative Commons wiki.

OER @ CU Libraries

When sourcing OER, ensure the resources you are using truly are OER, and of good quality, by visiting trusted open-source repositories. Visit our Open Educational Resources Guide to view lists of OER and websites related to your field of study. One great resource for finding open-source textbooks is the Open Textbook Library. This resource is maintained by the Open Education Network, a community of higher education institutions and educators creating inclusive educational environments through OER.

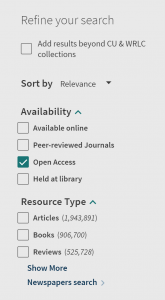

You can also use the library catalog to search for OER. Limit your results to open access resources by using facets. Facets are helpful tools that further define your search results list. Facets are seen on the left side of the results screen in our catalog. Navigating the world of OER can feel overwhelming at times. Consider using these tools and tips next time you are conducting research or working on a project. If you have additional questions about OER, email us or connect with a subject librarian.