Every two years, the ACRL Research Planning and Review Committee publishes in College & Research Libraries News an article on the top trends and issues affecting academic libraries and the change our institutions are experiencing. We will be highlighting some of these trends through a number of blog posts over the next few weeks.

When you think of AI, what comes to mind? There are dichotomous images in books and movies. In one view, there is the AI created to support and supplement the work of humans. In the other view, there is the robot uprising. In the library, AI and machine learning can be powerful tools. As with any tool created by man, AI can project biases or inaccurate readings into a situation. With that in mind, responsible and limited use of AI and machine learning can be a resourceful method of expanding limitations within libraries.

What is AI and machine learning?

Encyclopedia Britannica defines AI as “Artificial intelligence (AI), the ability of a digital computer or computer-controlled robot to perform tasks commonly associated with intelligent beings. The term is frequently applied to the project of developing systems endowed with the intellectual processes characteristic of humans, such as the ability to reason, discover meaning, generalize, or learn from past experience.” Machine learning is the branch of AI that programs computers to learn from experience. (Encyclopedia Britannica). John McCarthy, professor emeritus of computer science at Stanford University, coined the term ‘artificial intelligence’ during the Dartmouth Conference in 1956.

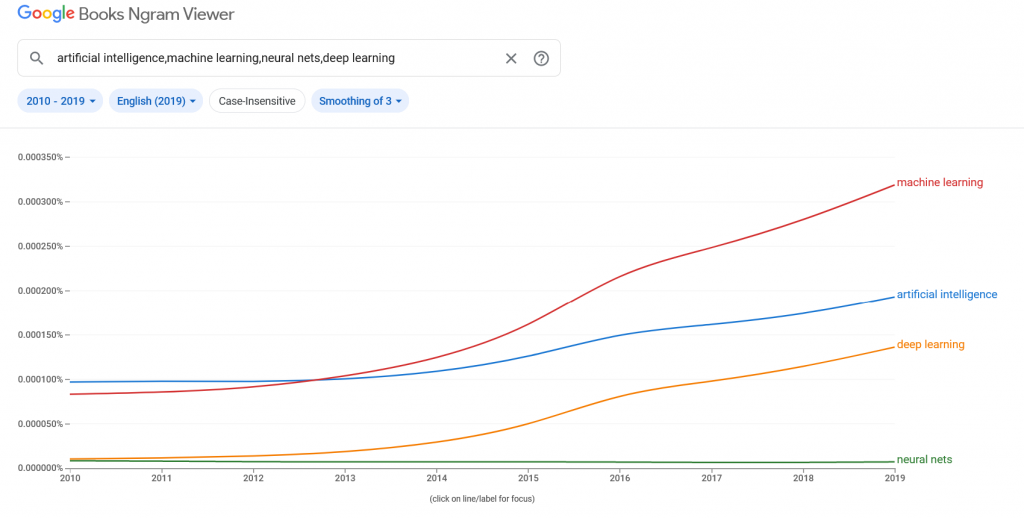

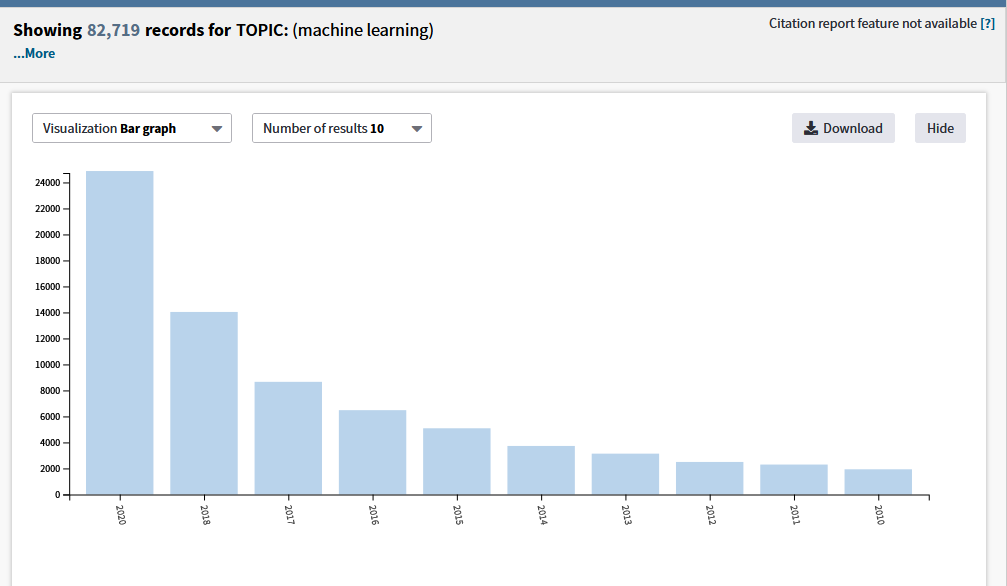

Growth of Research in AI Although the concept of artificial intelligence has been around for decades, popular awareness has grown exponentially. As popular awareness increases, so too does the number of research papers and books. An examination of the Google Books Ngram Viewer indicates a steep increase in the number of books published on the topic of machine learning. The same trend is also evident in the journal literature.

Web of Science shows 36,603 results for artificial intelligence and 105,220 for machine learning over the past 10 years. The past two years have seen the greatest growth, with an increase of 10,000 titles on machine learning between 2018-2020.

Libraries and AI

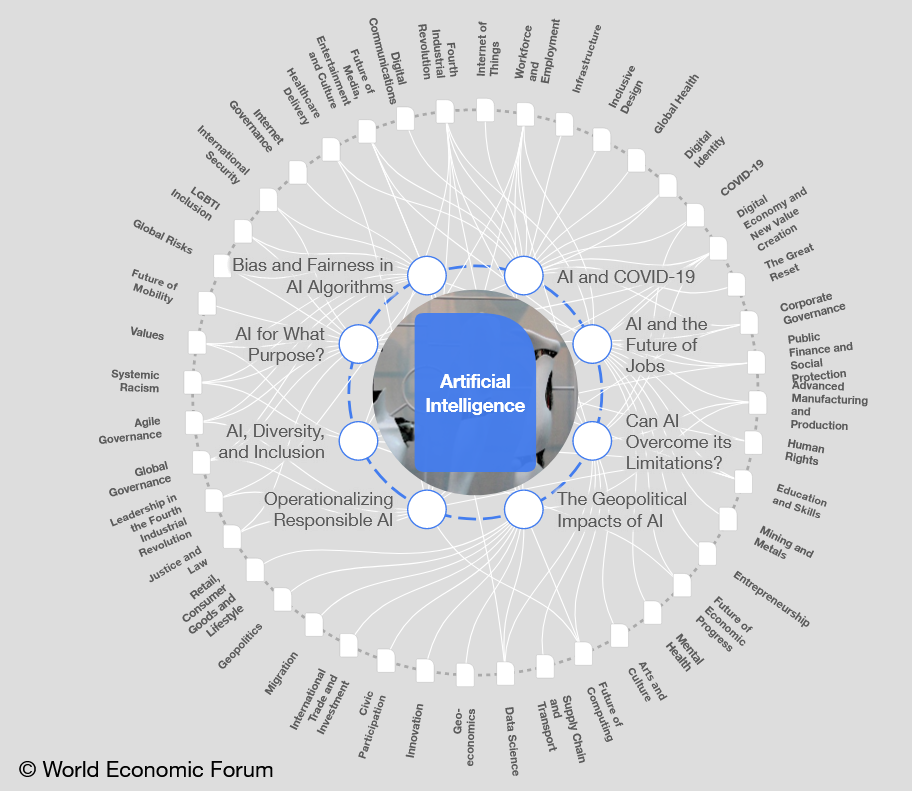

But what, you may wonder, does a library have to do with artificial intelligence? One lesson we have all learned from the COVID-19 pandemic quarantine is that libraries provide much more than physical collections. The infrastructure that provides access to ebooks, journal articles, and services online also provides access to the big data that could be used to analyze general user needs. For example, adding AI to a bibliometric analysis of required course readings could lead to a forecasting of student research needs, potentially improving student retention as the library pivots to meet those needs. With AI, library collections and services could become more individualized in much the same way that Amazon makes purchase recommendations based on past searches. AI has already changed the way many person-centered jobs are performed. “By 2022, today’s newly emerging occupations are set to grow from 16% to 27% of the employee base of large firms globally, while job roles currently affected by technological obsolescence are set to decrease from 31% to 21%. In purely quantitative terms, 75 million current job roles may be displaced by the shift in the division of labor between humans, machines, and algorithms, while 133 million new job roles may emerge at the same time” (World Economic Forum, Future of Work, 2018).

If you have a smartphone, consider how many times a day you turn to your device to check your calendar, search for the name of a song or an actor, watch a video, or even interact with other smart devices around you. During the pandemic, you may have had more conversations with Alexa or Google Assistant than with a real person. The question may occur to you whether an artificial intelligence bot could do as good a job at service occupations such as librarians. Research shows that acceptance of AI bots for service functions increases based on the anthropomorphism of the bot and the emotional ability of the person to accept AI. (Gursoy, 2019) While we may never see AI bots taking the place of librarians at a university library reference desk, librarians are already using AI to assist with research inquiries. Librarians help researchers navigate and understand the biases that algorithms develop. As Geneva Henry, Dean of Libraries at George Washington University writes, “Searching the internet using popular search engines, for example, can employ deep learning algorithms that continually learn from previous searches.” (Henry, 2019) Librarians often are called to help narrow a search and target the best results from hundreds of thousands that a search engine or database returns.

Ethics of AI

As with all software, AI can evidence the biases written into algorithms by humans. Additionally, because machine learning software is made to develop new neural networks, the algorithms can develop biases not initially observed. A bias can be as simple as listing the most likely link first in a results list, or as insidious as not recognizing the faces of people of color. To overcome bias in AI and machine learning, it’s important to work toward diversity and inclusion in the workplace and programming.

Additional Reading

B.J. Copeland, Artificial intelligence, Encyclopædia Britannica, August 11, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/technology/artificial-intelligence.

McCarthy, John, Marvin L. Minsky, Nathaniel Rochester, and Claude E. Shannon. (2006) “A Proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence, August 31, 1955,” AI Magazine 27, no. 4, 12–14, https://ojs.aaai.org/aimagazine/index.php/aimagazine/article/view/1904.

Gursoy, D., Chi, O., Lu, L., & Nunkoo, R. (2019). Consumers’ acceptance of artificially intelligent (AI) device use in service delivery. International Journal of Information Management, 49, 157–169, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.03.008

Henry, Geneva. (2019) Research Librarians as Guides and Navigators for AI Policies at Universities. Research Library Issues, 299, p. 47-65, https://doi.org/10.29242/rli.299.4

Griffey, Jason, ed. (2019) Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Libraries. Library Technology Reports, 55, no. 1, https://doi.org/10.5860/ltr.55n1

Kennedy, Mary Lee. (2019) What do artificial intelligence (AI) and ethics of AI mean in the context of research libraries? Research Library Issues, 299, p. 3-13, https://doi.org/10.29242/rli.299.1

Padilla, Thomas. (2019). Responsible Operations: Data Science, Machine Learning, and AI in Libraries. Dublin, OH: OCLC Research, https://doi.org/10.25333/xk7z-9g97

Young, Jeffery R. (2019) “Bots in the Library? Colleges Try AI to Help Researchers (But with Caution),” EdSurge, June 14, 2019, https://www.edsurge.com/news/2019-06-14-bots-in-the-library-colleges-try-ai-to-help-researchers-but-with-caution.27