[This article was written by Professor Robert Daibert Júnior from the Federal University of Juiz de Fora (Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora – UFJF).]

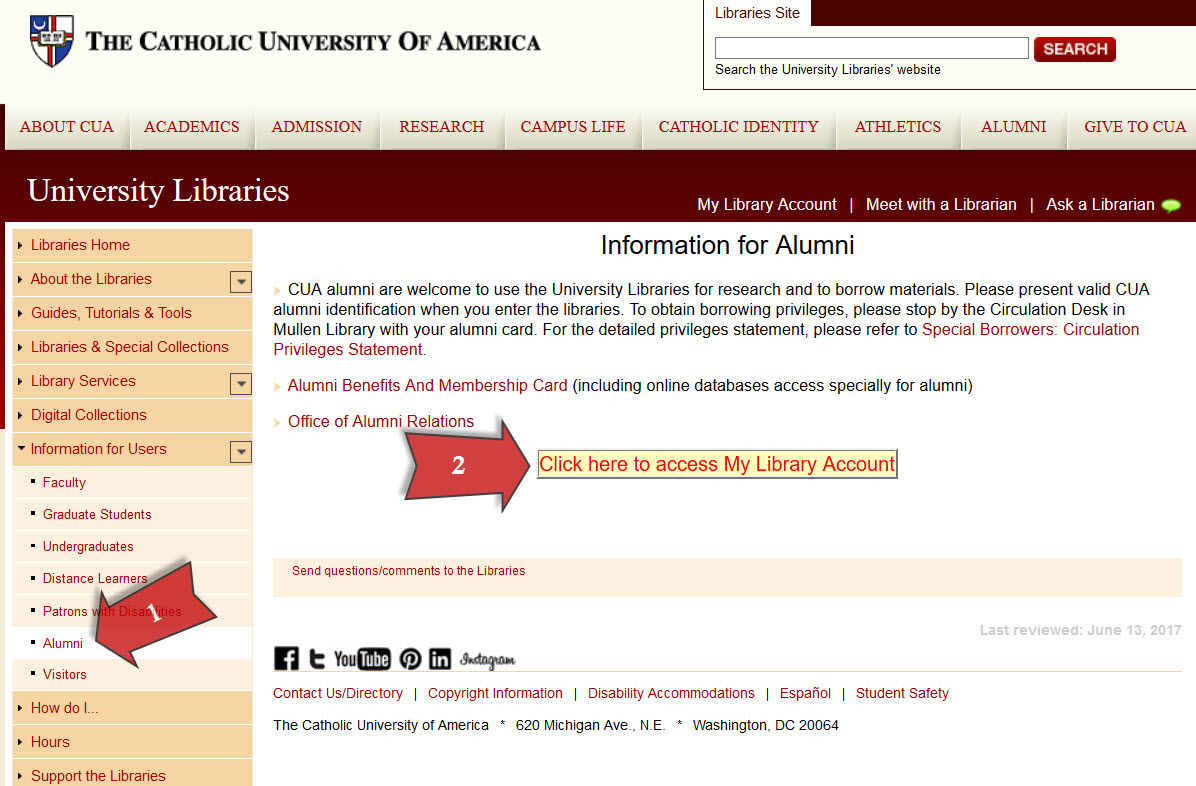

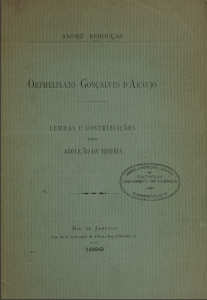

The rich history archives of the Oliveira Lima Library at the Catholic University of America, in Washington DC, holds a document forgotten by Brazilian History: a 59-page text published in Rio de Janeiro in October 1889, titled “Orphelinato Gonçalves de Araújo: lemas e contribuições para a abolição da miséria“. (“Gonçalves de Araújo Orphanage: mottos and contribution to the abolition of poverty”).

Its author is André Rebouças (1838-1898), a prominent abolitionist and one of the most active black intellectuals in 19th-century Brazilian society. In his fight to abolish slavery, especially in the 1880s, he advocated for an abolition project that included reforms in the country’s land structure, with small plots of land that would be distributed to formerly enslaved people. However, in May 1888, the Brazilian parliament approved a law declaring all enslaved people in Brazil free, albeit with no ways of gaining access to land nor guarantees of full and effective access to civil and social rights.

In Rebouças’ understanding, in 1888, slavery was only partially abolished in Brazil. With this in mind, in this 1889 text, he condemned the parasitic Brazilian elites, their privileges, and the severe consequences their actions had on holding back the country. In his analysis, in addition to the aristocracy who owned large plots of land, the author also included theocratic elites, represented by the Catholic clergy and their institutions, and the military elites, composed of the high ranks of the Navy and Army. In his view, these three segments hogged large land plots and survived unfairly at the expense of other people’s labor. Post-abolition, this format favored a predatory approach that enabled large fortunes, contributing to poverty and societal inequality. Rebouças’ 1889 text, which is still absent from History classes and unknown to the average contemporary reader, introduced ways to potentially solve this problem and pointed paths towards equity and social justice in Brazil.

In a quite utopian way, André Rebouças argued for the moral conversion of these elites based on the Christian principles of selflessness, equity, and altruism, drawing inspiration from the religious activism of Russian writer Leo Tolstoy. In his view, the ruling classes, motivated by this Christian humanitarian sentiment and the new legislation that would end their monopolies, privileges, and exemptions, these ruling classes would stop accumulating wealth and be led to give up their extensive lands. On top of that, Rebouças proposed a vast expansion of small properties occupied by families of formerly enslaved people or immigrants. These families had to adopt two to four destitute or orphan children in return for the land. (Rebouças, 1889: 20, 30-42)

Another very bold measure presented in the text is a project that provided for the legal abolition of the right to inheritance. In his words, this measure was “of utmost urgency to progressively evolve the altruistic feelings of the Human Species”. (Rebouças, 1889: 47-48) The new legislation could contribute to a moral change among the ruling classes, encouraging them to work and no longer accumulate riches. On the other hand, by increasing the number of small properties, it would be possible to create space for a new rural family, a promising cell for society. (Rebouças, 1889: 31-32) His fight to end slavery, for which he was best known, was just the “tip of the iceberg” of a much broader social reform project. In her words: “All social issues are simple equations encompassing Justice, Equity, and Morals. Every reform consists of abolishing, extinguishing, or declaring extinct an injustice, an inequity, and an immorality.”[2] Despite being a monarchist, Rebouças planned a liberal reform project for the monarchical regime itself, making it more democratic, developmental, people-focused, and secular.

As an engineer, André Rebouças worked on projects seeking to modernize Brazil by developing works that could elevate the country to the level of societies in the northern hemisphere. In this sense, he worked on hydraulic works to improve city supply, as well as on the construction of railways and docks. When working at seaports, he dived to monitor the underwater pilings. Rebouças was also a prominent professor at the Higher Education Polytechnic School in Rio de Janeiro, a position he secured after a public exam in which he presented his Ph.D. thesis, titled: “Estudo da Leis de Equilíbrio Molecular dos sólidos e sua aplicação ao empuxo das terras” (A Study on the Laws of Molecular Equilibrium of Solids and Its Application to Earth Buoyancy). He taught engineering students Physical and Natural Science, Architecture, Botany, Zoology, and, mainly, Endurance of Materials.

André Rebouças was a typical man of science of his time, with varied and wide-ranging interests. Despite his expertise in engineering, his interests and activities also included studies in Literature, History, Political Economy, Philosophy, Astronomy, and Physics, among others. As a successful intellectual and businessman, he traveled throughout the United States and various parts of Europe and Africa, especially Mozambique, South Africa, France, England, Portugal, Italy, and the Netherlands. Furthermore, he dedicated his entire life to intellectual and professional activities, always related to his intellectual (written) activism for social and political causes. He joined several scientific associations, particularly those dedicated to engineering and technological, cultural, and economic development projects for society. In all his endeavors, Rebouças recorded a vast written production and built a social network of intellectuals. His main references in the United States were Benjamin Franklin and Frederick Douglass.

When “Orphelinato Gonçalves de Araújo: lemas e contribuições para a abolição da miséria” was published, André Rebouças was also working on an Socionomic Encyclopedia. It was inspired by the assumption that just like scientific studies explained the laws of how the physical world functions (Newton) and how the species evolve (Darwin), it was necessary to find a science to describe the laws of how societies work and change. Rebouças set out to lay the foundations of a new science focused on society and social inequality, inspired by Tolstoy’s Christian argumentation for an altruistic science capable of promoting social equity, following the Gospel principles. It was an ambitious epistemological project that never came to fruition but was outlined in a series of other texts related to the principles he laid out in this 1889 document.

Two weeks after “Orphelinato Gonçalves de Araújo: lemas e contribuições para a abolição da miséria” was published, André Rebouças’ plans for the country came to a halt. On November 15, 1889, an Army-led military coup overthrew the monarchy in Brazil. As a monarchist, Rebouças initially accompanied the Brazilian imperial family into exile in Portugal and France until 1891. From his point of view, the implementation of the Republic was a result of large landowners’ and former enslavers’ resentment, who felt they had the right to compensation due to the abolition of slavery. In his words, the end of the monarchy was a “revenge of the Landlords, enslavers of Africans and Italians, and usurpers of the national territory”.[1] After a trip to Africa between 1892 and 1893, Rebouças moved to Madeira Island and never returned to Brazil. He was found dead at sea in 1898 on the edge of a cliff in the city of Funchal.

If, on the one hand, Rebouças had some prestige in Brazilian society, when disputes arose, his merits and intellectual competence were constantly attacked on racist grounds. Being a black man in an enslaving, racist society undoubtedly hindered the spread of his ideas. His quest to become a renowned intellectual was marked by constant struggles, tensions, and obstacles that are directly related to the constant racism that permeated his life. One of the main challenges was dealing with the legitimation of racism enabled by the science of the time to build epistemological alternatives to the ruling hegemonic models. Unfortunately, his rich trajectory and the content of his ideas fell into oblivion and have not yet been properly recognized in Brazilian History. In this sense, reading and analyzing the text “Orphelinato Gonçalves de Araújo: lemas e contribuições para a abolição da miséria” contributes to the expansion of knowledge and appreciation of his intellectual legacy. New investigations on his 1889 text could contribute to the study of a black intellectual who is still largely invisible behind a veil of racist silence that persists in denying the protagonism he and many other black people hold in science and societies at large.

References:

- Letter from André Rebouças to José Joaquim de Maia Monteiro (Barão da Estrela). Lourenço Marques, May 16, 1892. In: MATTOS, Hebe. Cartas da África: registro de correspondência (1891-1893). Rio de Janeiro: Chão, 2022, p. 154.

- REBOUÇAS, André. Imposto Territorial. Revista de Engenharia, Rio de Janeiro, n. 208, 28 Apr. 1889, p. 85.

- REBOUÇAS, André. Orphelinato Gonçalves de Araújo: lemas e contribuições para a abolição da miséria. Petrópolis: Typ. G. Luizinger e Filhos, 1889.

About the author:

Robert Daibert Junior has a teaching and a bachelor’s degree in History from the Federal University of Juiz de Fora. Masters in History from UNICAMP. Ph.D. in History from UFRJ. Associate Professor IV at the Federal University of Juiz de Fora, where he works in the Postgraduate Program in History and the Postgraduate Program in Science of Religion. His expertise is Brazilian History and Religion, mainly on the following topics: religion in the thoughts of black intellectuals; religion and writing the self; African religion and literature; religion, slavery, and abolitionism; religious experiences of enslaved people. He is the coordinator of the Research Center on African and Afro-Brazilian Religions (Núcleo de Pesquisa em Religiões Africanas e Afro-brasileiras, NUPRAAB-UFJF) and member of the Laboratory of Oral History and Image/Afrikas (Laboratório de História Oral e Imagem/Afrikas, LABHOI/AFRIKAS-UFJF). His research is integrated to the Past Presents Project: the memory of enslavement and Brazil after the abolition (Projeto Passados Presentes: memória da escravidão e do pós-abolição no Brasil), a research network that involves LABHOI/UFF, the Center for Latin American Studies at the University of Pittsburgh (CLAS-PITT-USA) and the Centre International de Recherches sur les Esclavages (CIRESC) of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS/France). He is a Consultant for the Past Presents Project: Afro-indigenous Heritage and Memories in Minas Gerais (Projeto Passados Presentes: Patrimônios e Memórias Afro-indígenas em Minas Gerais)