One hundred years ago, American entry into the First World War transformed the nation’s capital from a sleepy Southern crossroads into a modern hub of administration commensurate to an emerging first class world power. It was here a young Catholic soldier wrote his family, primarily his mother and sisters, back in their hometown of Southington, Connecticut. That man, Robert Lincoln O’Connell, whose archival papers, including a digital collection, reside in the archives at The Catholic University of America (CUA) and briefly alluded to in two previous blog posts, ‘For God and Country’ and ‘World War I on Display,’ contain seven letters he wrote from April to August 1917 addressed from Washington Barracks, now Fort McNair. ‘Rob,’ as he was known to his family, described his initial training in and around Washington, D.C. as a combat engineer, or sapper, for service in the First Engineer Regiment of the First Infantry Division of the American Expeditionary Force (A.E.F.) in France.

O’Connell (1888-1972), a native of Wareham, Massachusetts, was the eldest of five children of Daniel and Mary O’Connell, immigrants from Ireland and Wales, respectively. By 1900, the O’Connell family had moved to the town of Southington, Connecticut, near Hartford and less than 100 miles from New York City. The family attended St. Thomas Roman Catholic Church and the 1910 federal census lists father Daniel as a “laborer” in an “iron mill” and son Robert as “laborer” in a “hardware shop.” Rob O’Connell enlisted in the U.S. Army at Fort Slocum, New York, on April 14, 1917, and shortly thereafter transferred to Washington Barracks where he spent the next three months training as a machinist in Company C, First Battalion, of the First Engineers. His unit also spent time along the Potomac River on the grounds of the Belvoir Estate that had served since 1912 as a rifle range and summer camp for the training of Army engineers.

In O’Connell’s April 28, 1917 letter, he told his mother details of settling in after his recent enlistment and commented on the visit of Marshal Joseph Joffre, famous hero of the Battle of the Marne, who spoke at the Army War College, adjacent to Washington Barracks, the day before. “All clothes had to be sent to the disinfecting plant to prevent spreading disease among so many men…. Gen. Joffre and his party visited the post yesterday. I seem to be hungry all the time, in spite of three sq. meals.” Writing in mid-May, he complained to his mother about the Washington newspapers, presumably the Washington Post and Washington Star, although he appeared impressed by D.C.‘s sites and scenes. “This city has trees along the main streets. I never saw a place like it. I have not seen Mr. Lud, the President, yet. But I have seen the principle buildings and the Wash. Monument, which you can’t help seeing, it is so tall.”

Apparently, ‘Mr. Lud’ was a nickname for President Woodrow Wilson, perhaps an obscure reference to the legendary British king and founder of London. Writing his mother again on May 31, he explained the training of engineers at Washington Barracks. “They had racing and other sports between the companies…We lost the tent-pitching by a few points…The sergeant was sore at losing and yelled at us as we marched off the field.”

In June, he told his mother “There was a black and white scrap up the street, last night.” An African-American woman had an argument with a soldier and “she hit him with a beer bottle.” This was probably not an isolated incident as the August 10 Washington Post said the Secretary of War directed “a number of saloons in Four-and-a half street southwest may be closed because of their proximity to the Washington barracks.” Another letter home, also written in June, addressed to his sister Ellen, described field training on the grounds of the future Fort Belvoir. “I have just put in the hardest two weeks of my life, I guess, down at the rifle range. It is about twenty miles below Washington, on the Potomac… passengers on the passing steamers probably wish they were camping out there. But when we (A, B and C companies), got there two weeks ago last Monday, there were no tents and lots of brush and weeds and hard work…For two days we worked around camp and lugged and tugged and sweated and wondered why we had ever wanted to leave our happy home at the Barracks.” Combat engineers learned to construct field works and pontoon bridges. They also had to fight as regular infantry when the need arose, hence training in the use of firearms. “Half the company shot in the forenoon while the other half worked in the pits, pushing the targets up into view and pointing out each hit with a long stick… I fired in the morning and managed to get in with the higher ones on the score.”

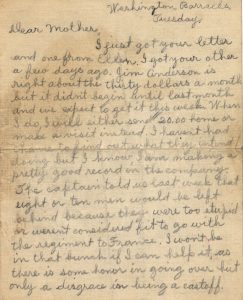

O’Connell wrote his mother on July 3 expressing confidence in himself as well as contempt for those who had not met the standard. “The captain told us last week that eight or ten men would be left behind because they were too stupid or weren’t considered fit to go with the regiment to France. I won’t be in that bunch if I can help it, as there is some honor in going over but only a disgrace in being a castoff. When the news first got out a month ago, that we were going to France, some of the fire-eaters were delighted, until the officers explained what they would have to do…It was no news to me and if I go, I will do the best I can. This life is a wonderful bracer and I am glad I joined.” The last letter, addressed to his mother in early August, was written a few days departure for France. “Would you care to make the trip down and risk finding us gone?” There is no record his family made the trip to see him. The First Engineers left Washington on August 6 and embarked for France from Hoboken, New Jersey, the following day. O’Connell and his fellow engineers were now at war and a future blog post will explore their time at the front in 1918.

Thank you. A very good read. Primary sources rule!