This week’s post is guest-authored by Austin Powell, a graduate student in History at Catholic University.

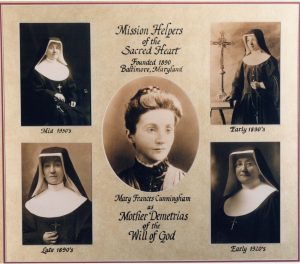

On November 14, 1904, Demetrias Cunningham, a daughter of Irish immigrants and now Mother Assistant of a young order of American nuns called the Mission Helpers of the Sacred Heart, wrote to a Pittsburgh priest: “Our sisters now in Pittsburg [sic] have written to say that you are very much interested in the Italians in your city – and seem desirous to know more of our work, prior perhaps, to having a small band of our sisters to work amongst these poor people. We enclose a report of the work done generally by our Community and will also give an outline of it amongst the Italians.” Demetrias goes on to explain how the Mission Helpers sought to catechize recent Italian immigrants in three Mid-Atlantic American cities at the turn of the century: Demetrias’s native Baltimore, and the New Jersey cities of Trenton and Atlantic City.

Between 1880 and 1924 Eastern European immigrants arrived by the millions to the United States. This was only the latest in a series of mass migrations which led to an ever changing dynamic as people who spoke different languages, practiced different religions, and identified as different races and ethnicities lived together and interacted, sometimes peacefully but other times not. Indeed, anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic sentiments reached a fever pitch in the 1910s and 1920s, culminating in 1924’s Johnson-Reed Act which established quotas regarding the national origins of arriving immigrants, effectively outlawing immigration from Asia and steeply cutting the numbers of Italians and eastern Europeans allowed entry to America.

Scholars have recognized that the archives and papers of religious organizations can provide insights into branches of American history outside the strictly religious, such as labor or immigration. And because of the nature of their work the collection of these Baltimore nuns, which entered the Catholic University Archives in 2014, provides ample evidence for how communities of different nationalities, races, and religions engaged each other in America’s cities around 1900.

In 1890, Anna Frances Hartwell (an Anglican convert to Catholicism) adopted the name Mother Joseph and founded the order in Baltimore. Originally, the group was entirely dedicated to missionizing the predominantly Protestant African American population of Baltimore; however, after 1896, the scope of the Mission Helpers’ ministry expanded to people of all races. They soon had a particular focus on ministering to deaf Catholics as well as the many Italians settling in America. The nuns also opened houses in 1902 and 1905 in the recently conquered Spanish territories of Puerto Rico and Guam.

In her 1904 letter, Mother Demetrias, who served as Mother Joseph’s deputy, describes how the Mission Helpers established catechism classes for young Italian boys on weekday evenings in Baltimore. The nuns also managed evening classes in “secular studies” (i.e. reading and writing) for those same boys. In Trenton the nuns had a “Home Training School” for Italian children, teaching them to respect their elders and how to clean their linens; meanwhile, in Atlantic City the nuns conducted sewing classes for Italian girls. It was not only the tenets of the Catholic faith the nuns wanted to impart to these new arrivals, but also more practical skills which would help them operate in American society.

However, Mother Demetrias notes that the nuns first had to build bonds of trust with the Italian parents before they could convince them to send their children to the Mission Helpers’ schools. To do this they would visit the immigrants in their homes, staying for ten or fifteen minutes at a time “and in this way we get acquainted with the family, talk to them on indifferent subjects, until they learn to know us.” As almost all the Mission Helpers in these years were Irish immigrants or the children of Irish immigrants, many of the sisters had to learn Italian to better minister to that growing community; indeed, the collection holds more than one example of Italian lay-people living in American cities writing letters to the Mission Helpers in their own native tongue.

Mother Demetrias emphasizes that the purpose of their work was to convince Italians, young and old, who had not gone to Mass to receive the Sacraments “sometimes for three, four, five as many as ten years,” to reform their lives in accord with Catholic teachings and practice. Yet a 1921 report the Mission Helpers’ sent to the Vatican provides further explanation. In the later document it becomes clear that competition with Protestants was a top concern for the nuns. Indeed, they note that in Trenton they opened their Sunday School for Italian children in the same building some Protestants were holding theirs, thereby “rescuing nearly all these children.” In New York the sisters claimed there were “14 different Protestant sects busily proselytizing” the immigrants, and one man, an excommunicate, in Staten Island called “Di Santo … has succeeded in deceiving many.”

The letters and reports of the Mission Helpers reveal much about Catholic-Protestant competition for the souls of recent immigrants at the turn of the century, as well as the methods these women used to minister to a variety of different groups in the United States, including African Americans, Italians, Puerto Ricans, and deaf people. The records of the Mission Helpers are held at the Archives of Catholic U. For more information, please email

lib-archives@cua.edu

Great post. Do you hold the archives for the Mission Helpers/

Yes.

Thank you for this article. Mother Demetrias was my great, great Aunt.