Yes, a “labor priest” is a thing. His origins can be found in the intersection of the rise of the modern working class in the nineteenth century and the issuance of the encyclical Rerum Novarum in 1891. The labor priest usually materialized from a working class community, often with immigrant roots, and often possessed an organic awareness of issues affecting the people in those communities. The late nineteenth and early twentieth century saw the rise of conflicts between employers and employees in the wake of industrialization in the United States, much of it centered on the question of whether employees could form unions and collectively bargain with employers through these organizations. The CUA Archives has a very strong collection of materials related to Catholicism and labor, including rich collections related to three individuals known as “labor priests”: John Ryan, Francis Haas, and George Higgins.

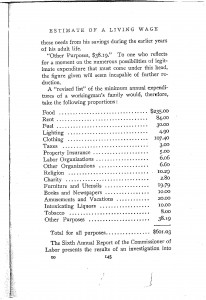

The trailblazer of the labor priests was Monsignor John Ryan, a professor of moral theology and ethics at The Catholic University of America (CUA) from 1915 until 1939. Ryan was electrified when he read the encyclical Rerum Novarum in the 1890s, noting that “The doctrine of state intervention which I had come to accept and which was sometimes denounced as ‘socialistic’ on those benighted days, I now read in a papal encyclical.” Ryan drew inspiration from the encyclical to dream up a whole host of reforms aimed at improving the condition of the American worker. Realizing that very little research had been done on what it actually took to survive economically in America, Ryan wrote “A Living Wage,” the first book published on the subject in 1906. Ryan did extensive research into living wage issues, worker rights, and employer-employee obligations, and wrote a program of reform for the U.S. Bishops that was largely adopted during the New Deal years. Later, he served on the Fair Employment Practices Commission and advised various individuals in the Roosevelt administration on workplace issues. Ryan’s papers are a rich chronicle of a progressive Catholic reformer in the early twentieth century.[i]

Another labor priest also inspired by Catholic social teaching in addition to Ryan himself was Francis Haas, a Wisconsin-born professor of social science at CUA from the 1930s until he was named Bishop of Grand Rapids, Michigan in 1943. Where John Ryan preferred study, theorizing and figuring, Haas preferred application. As Monsignor George Higgins, a student of both men put it, “Ryan originated ideas, Haas put them into practice.” Haas loved to work with people. On campus he delivered talks to jam-packed rooms of students on labor-management issues on Sunday mornings after mass. His specialty was labor arbitration. As a Department of Labor mediator, he helped settle 1500 labor strikes from when he started arbitrating in the early 1930s until his death in 1953, and was referred to by one Catholic weekly as “the ace of federal peacemakers.”[ii]

George Higgins was an enthusiastic attendee of Father Haas’s lectures upon his arrival at CUA in the early 1940s. The Chicago-born priest believed that “the church makes visible its presence in the labor movement.” That being said, Monsignor Higgins had some great mentors on this topic, including Ryan and Haas. Underscoring the hybrid that was the twentieth century labor priest, he considered Ryan “an Irish-American farm boy” with “an earthy” sense of humor, while at the same time calling him “the intellectual architect of American Catholic social action.” Haas “had the look of a St. Bernard dog, big and shaggy-haired” Higgins asserted, and “believed that workers had not only a right to join labor unions but a sacred obligation to do so, in view of our nature as social beings.”[iii]

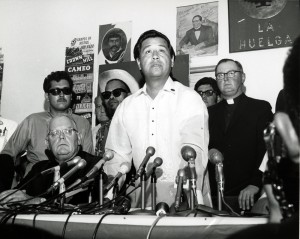

Higgins, too, served as an arbitrator in labor disputes, perhaps most famously, on the US Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Farm Labor Committee in support of Cesar Chavez and the farm labor union movement. By the time he passed in 2002, however, he had come to occupy a unique position among labor priests: communicator. As former Secretary-Treasurer and President of the AFL-CIO put it, Higgins occupied “an utterly unique role” “in the church and union movement: “he has been a kind of translator who knows the subtle dialects of Catholics and trade unionists, and he has a remarkable gift for translating the dialect of each group into terms that the other can understand.” Accordingly, Higgins spent much of his adult life working for the Bishops’ Conference in a translator capacity, clarifying the Catholic teachings on many topics, but especially matters related to labor. His papers are a fine resource for understanding the official Catholic position on labor in the second half of the twentieth century.

[i] John A. Ryan, Social Doctrine in Action, A Personal History (New York, 1941), 9-40; A Living Wage (New York: Grosset and Dunlap) 145.

[ii] George Higgins with William Bole, Organized Labor and the Church, Reflections of a ‘Labor Priest’ (New York: Paulist Press, 1993), 31; Thomas E. Blantz, “Father Haas and the Minneapolis Truckers’ Strike,” Minnesota Historical Society Magazine, Spring 1970: url, retrieved 2/26/16: http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/42/v42i01p005-015.pdf).

[iii] Higgins, Organized Labor and the Church, 1, 5, 26, 31.

4 thoughts on “The Archivist’s Nook: What the Heck is a Labor Priest?”

Comments are closed.