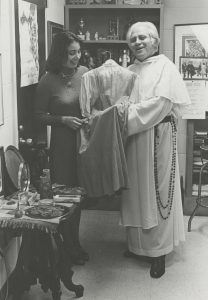

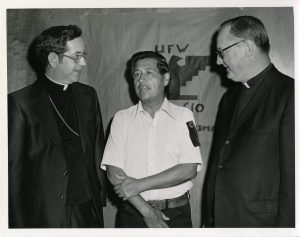

Monsignor George Higgins was a member of the U.S. Catholic clergy, director of the Social Action Department of the forerunner of today’s U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, attendee to the Vatican II Council, and an authority on labor relations. Cesar Chavez was a farm worker, a lay member of the Church, and a union leader who was on the ground floor of a revolution in farm labor organization.

Together, these two Catholics made for a potent combination that helped bring a degree of labor justice to agricultural workers in California and other parts of the United States. Chavez and his United Farm Workers union sought higher pay and better working conditions for domestic agricultural laborers, using strikes and boycotts to induce growers to come to the bargaining table. Higgins and the Bishop’s Ad Hoc Committee on Farm Labor became a forceful negotiator between the growers and the workers. The combination eventually led to thousands of workers finding representation under the auspices of the United Farm Workers union. Today, people hold the memories of both men dear for their unrelenting crusade to enhance the lives of the workers in the fields.

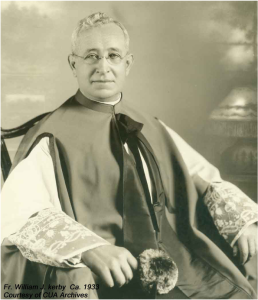

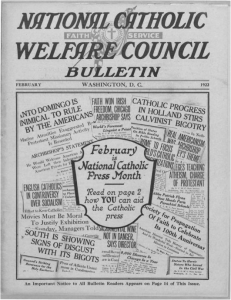

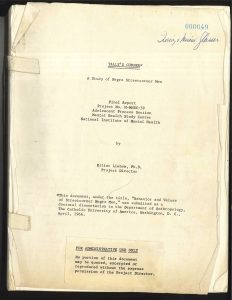

Born in Chicago, Illinois, Monsignor George Gilmary Higgins (1916-2002) developed an interest in labor issues from an early age, carrying this interest with him into seminary in Illinois and graduate work at The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. Upon finishing his four years of study at Catholic University in 1944, Higgins immediately went to work for the National Catholic Welfare Conference’s Social Action Department (SAD), where he would remain for the next 36 years, serving as the department’s director from 1954 to 1967. He also took over the authorship of the syndicated column The Yardstick from legendary SAD director, Father Raymond McGowan. The column afforded Higgins the opportunity to speak on labor and social problems, among other matters of the day. While Higgins would become involved in numerous social causes during his tenure, he gained his nickname of “The Labor Priest” for one reason: his lifetime support for workers and labor unions. It was this support that would lead Higgins and other clergy to the cause of farm workers of California and a charismatic labor leader in Cesar Chavez.

Cesar Estrada Chavez (1927-1993) was born in Yuma, Arizona, in 1927 to a Mexican-American family. Due to struggles during the Great Depression, the family moved to California to become migrant workers. Chavez labored in the agricultural fields before joining the U.S. Navy in 1944. After returning from World War II, Chavez married Helen Fabela, and they moved to San Jose, California. Chavez continued to work as a farm laborer until he became interested in unionization. Many agricultural businesses relied on migrant workers, mainly Mexican-Americans or Mexican immigrants, to work their fields, and the growers rarely showed any interest in the well-being of their laborers. Chavez became an organizer first for the Community Service Organization, then co-founded the National Farm Workers Association with Dolores Huerta in 1962 to improve conditions for laborers. The Association later evolved into the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee (UFWOC), then the United Farm Workers (UFW), a union that led strikes against numerous vegetable and fruit growers and worked to draw farm laborers into its organization. The work of Chavez caught the attention of many nationally, including Church clergy, due also to Chavez’s strong Catholic faith. This attention led to his meeting with Higgins and other clergy.

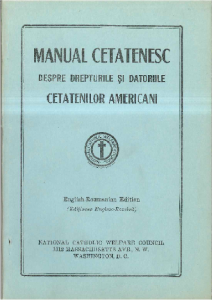

Since the late 19th century, the U.S. Catholic Church has had a strong connection to labor. The issuance of the encyclical Rerum Novarum by Pope Leo XIII established the Church’s support for organizing labor in 1891, institutional support reiterated through papal teachings throughout the twentieth and into the twenty-first century. Since then, clergy and laity have pled the cause of the working classes in metropolitan areas down to the smallest farms, standing on picket lines and encouraging legislation to support unions and laborers. The Church, particularly a committee of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops (a forerunner of today’s U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops), would become involved in a high-profile labor dispute in 1970 by seeking to negotiate contracts between large agricultural farms and laborers in California. While the UFWOC had been laboring for five years to conclude such contracts with growers with minor success, the work of the Ad Hoc Committee on Farm Labor of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops (NCCB) in 1970 and after would help the union even more in the years to come. At the heart of this cooperation was Monsignor George Higgins of the Ad Hoc Committee and Cesar Chavez of the UFWOC and UFW. The two men would work tirelessly to achieve economic justice for the field laborers in need of representation.

Eventually, the organizing and publicity campaign of Chavez and the UFW bore fruit, as national support for the farm workers grew. The California Agricultural Labor Relations Act (CALRA) passed the state’s legislature and was signed into law on June 4, 1975 by Governor Jerry Brown. CALRA established the right to collective bargaining for in that state, a first in U.S. history. The law explicitly encourages and protects “the right of agricultural employees to full freedom of association, self-organization, and designation of representatives of their own choosing, to negotiate the terms and conditions of their employment, and to be free from the interference, restraint, or coercion of employers of labor, or their agents, in the designation of such representatives or in self-organization or in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection.”

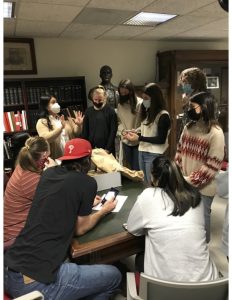

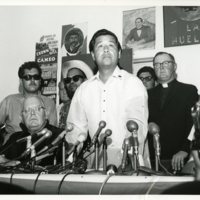

A new exhibit in the Mullen Library second floor reading room (from February through May 2024) presents objects, articles, photographs, and letters from the George Higgins collection detailing the story of the Catholic Church and the United Farm Workers (UFW) during the drive to unionize farm workers. Through these objects, a picture of cooperation between organizations seeking to better the lives of thousands forms, showing that social change is possible or, in the words of Chavez: “Si se puede” (“It can be done”). A digital exhibit can be found here.