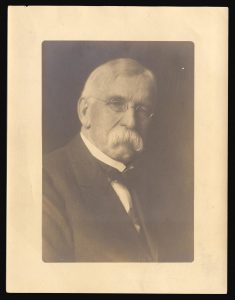

In January, 2000, the U.S. Department of Labor held a ceremony in Washington, D.C. to honor Terence Vincent Powderly (1849-1924), the 1999 Labor Hall of Fame inductee. He joined fellow Hall-of-Famers such as rival Samuel Gompers, friend Mary Harris “Mother” Jones, and fellow Pennsylvanian and labor leader Philip Murray. The Labor Department Report announcing the honor referred to Powderly as a “little known leader,” then went on to delineate his accomplishments. Powderly himself might have been a little offended at the reference to his obscurity, and not without cause. He was an extremely popular leader in his time. People wrote celebratory songs and poems about him and hung his portrait in their homes. He was often greeted with cheers and celebration in his extensive travels promoting the Knights. William Mullen, a Knights leader and organizer in Richmond, Virginia, named his son Terence Powderly Mullen when the boy was born in 1885. With many, many friends in the labor movement, and as a committed leader who cared about individuals ruthlessly exploited by corporate power, Powderly can be understood as a representative of the collective will of late-nineteenth century labor. We have selected objects from his voluminous collection, housed at the University’s Archives, for a display open to the public in the Archives’ Reading Room on the centenary of the penning of his autobiography, The Path I Trod.

Powderly’s massive popularity in the late nineteenth century was not necessarily foretold by his humble beginnings, though his personal story lent to his credibility among labor’s rank and file. He himself thought his story was worth telling enough to labor over it. Quoting Benvenuto Cellini that one who had “done anything of excellence” ought to “describe their life with their own hand,” (The Path I Trod, 3) Powderly set out to describe what he saw as the major events of his life: his youth in Pennsylvania’s coal country, early interest in labor unionization, years as the Mayor of Scranton, Pennsylvania, involvement in American politics, and civil service as U.S. Commissioner General of Immigration.

Young Terence’s parents came to the United States from Ireland in 1827 for the same reason thousands of other Irish did: to seek the opportunity to work and raise a family outside of the oppressive conditions of British-ruled Ireland. Terence was born in what would become Carbondale, Pennsylvania, on January 22, 1849. Anthracite coal had just been found in the area, heralding the industrial growth of the Scranton region as a coal- and iron-mining center. The rail industry, a fascination for Powderly as well as a source of early employment, developed concomitantly in the area during his youth.

Powderly describes his childhood home as cold and drafty, with “no lathes, no plaster, and when the wind blew the house would rock as well as the cradle.”(8) The eleventh of twelve children, young Terence served as “the coal-breaker of the family at a time when coal was delivered “in lumps just as it came from the mine, few of them smaller than one’s head.” (14) He also helped his mother maintain the house, cleaning, cooking, and churning butter, according to his account, as a boy. At thirteen, Terence went to work as a switch operator for the railroad, eventually apprenticing as a machinist with James Dickson at age 17.

Working conditions in the age of burgeoning industry caused many workers to join labor unions, and Powderly was one of them—he joined the local Scranton unit of the Machinists and Blacksmiths International Union in 1871, soon becoming its secretary, then president. Shortly after marrying Hannah Dever in 1872, he was fired from his job as a mechanic for his union work and “walked the [railroad] ties” into upstate New York and Canada looking for work. (26)

Rather than back away from his labor activism, however, Powderly leaned into it further. He gave speeches on the importance of unionization. He wrote articles for trade journals and newspapers. He also studied and practiced law, which certainly strengthened his mediation skills (and helped pay the bills). In 1874 he was elected a union delegate for several districts in Pennsylvania. Unknown to Powderly, the Noble Order of the Knights of Labor was founded by Uriah Stephens and a group of tailors in Philadelphia in 1869. “While the Knights of Labor were secretly working their way to light and a world’s recognition,” he notes, “I had never heard of that order.” (42) The order maintained secrecy to protect its members from employer retaliation.

Later that year, however, Powderly attended an anti-monopoly convention in Philadelphia and was invited to join the Knights, though he wasn’t initiated until September 1876. After that, “I knew no waking hour that I did not devote, in whole or part, to the upbuilding of the Order.”(45) Powderly’s work resulted in his being elevated to the organization’s General Master Workman (the union’s highest office) in 1879.

The Knights’ approach to generating change was both local and national. Between 1869 and 1896 the order found its way into every state, comprising 15,000 Local Assemblies with over 700,000 members by 1886. The Knights found community, solace, and valuable information in their local meetings throughout the country. Local Knights organized and sponsored lectures and study clubs that were aimed at educating workers in economic principles. Women and Black Americans also had their own units, though the order specifically discriminated against Chinese laborers.

The Knights, however, declined in power by the late 1880s. A strike they led in 1886, the Great Southwest railroad strike, was unsuccessful, causing a decline in membership. The Knights suffered another blow that same year when they were associated with the tragic Haymarket Affair, a bombing in Chicago that took place during a worker’s rally in the city’s Haymarket Square. Finally, the founding of the American Federation of Labor by Samuel Gompers in 1886, drew skilled workers into its ranks, and away from the Knights. By 1889 Knights of Labor membership had dwindled to 120,000. Powderly resigned as Master in 1893.

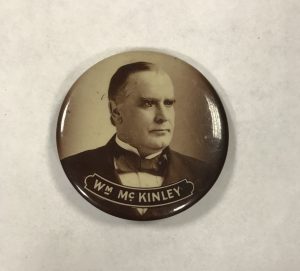

Powderly was elected Mayor of Scranton, Pennsylvania on the Greenback-Labor Party ticket for three two-year terms from 1878-1884. That he was still under 30 years old when first elected is a testament to his political skill. Though known primarily as a labor leader, politics came with the territory, especially in the politically and economically tumultuous years of the second industrial revolution. After he left his leadership position with the Knights of Labor in 1893, he became more involved in local, and eventually, national politics. He first met William McKinley in 1881 during a coal miners’ dispute in Ohio. McKinley, a lawyer, took up the case for miners accused of unlawful assembly without payment, as the miners couldn’t pay for counsel. This earned McKinley Powderly’s lasting admiration, and the two became good friends. McKinley was a Congressman from Ohio at the time, but would serve as U.S. President from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. Powderly describes him as “a man who had a heart that felt for others’ woes; he was unpretentious, unassuming, and kind.” (296) The Powderly papers contain numerous tokens of Powderly’s support and affection for McKinley. McKinley, for his part, appointed Powderly Commissioner General of Immigration in 1897.

Ellis Island was the main port of entry during Powderly’s term as Commissioner. Arriving at the immigration station, however, he saw “that all was not well… ill treatment of arriving aliens, impositions practiced on steamship companies, and discourtesy to those who called their meet their friends on landing were frequent.” (299) Powderly created a commission to investigate conditions at Ellis Island that resulted in charges of corruption and nearly a dozen firings. Powderly himself lost his position when McKinley was assassinated in 1901, though he was appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt Special Immigration Inspector in 1906. This position entailed travel to Great Britain, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Italy, and Austria-Hungary to study the causes of immigration. An avid amateur photographer, Powderly took copious photos as he traveled, some of which are digitized and can be viewed here.

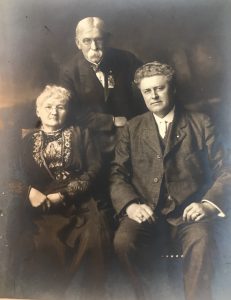

Powderly’s final position, 1921-1924, was as Commissioner of Conciliation of the U.S. Labor Department under James J. Davis (1873-1947), who served as U.S. Secretary of Labor, 1921-1930, under Presidents Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover. Powderly died in Washington, D.C., on June 24, 1924.

The exhibit on Terence Powderly featuring the objects pictured here, along with many others from the collection can be viewed by the public in the Archives’ Reading Room in 101 Aquinas Hall.

References: Terence Powderly, The Path I Trod (New York: Columbia University Press, 1940)