As the United States Catholic population boomed between 1890 and 1920, national Catholic institutions evolved to address their needs. A key player in these developments was the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. Initially established in 1917 to coordinate Catholic activities related to the First World War, the National Catholic War Council evolved into the National Catholic Welfare Conference (NCWC), the forerunner of today’s U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB). At the heart of the story of the USCCB’s formation is a tale of how a hierarchical institution like the Catholic Church adapts itself to thrive in a pluralistic and democratic society. The archives holds the records of the USCCB, which clock in at over 1000 boxes of archival materials!

When the United States entered World War One in 1917, authorities called for volunteer participation by private individuals and organizations to support the war effort.

Among these volunteers was the Catholic Church, which was broadly perceived as an immigrant body whose patriotism was suspect and whose members were untested in their loyalties, at least from the non-Catholic perspective.

Responding to this challenge under the motto of “For God and Country,” American Catholics led by the Paulist Father John J. Burke created the National Catholic War Council in 1917. Father Burke (1875-1936) was the heart and soul of the newly emerging bishops organization. He saw a fundamental compatibility between the principles the U.S. was founded upon, and those of the Catholic Church. He believed that the principles of the Constitution would lead to Catholic truth if they were fully followed.

The War Council represented the first coming together of the American bishops in voluntary association to address great national issues affecting the Church. Burke would head the Council’s Committee on Special War Activities, which oversaw mobilization of lay men and women in the war. The War Council worked particularly with the Knights of Columbus to provide education and recreation to Catholic men serving in the war. Also, the Council set up Catholic settlement houses in cities across the country to improve the civic education of immigrants and urged every diocese and Catholic organization to set up their own “Americanization” programs.

Many in the American Hierarchy soon realized with Father Burke that this united and coordinated effort in wartime might be reorganized for use in promoting Church interests in peacetime. This resulted in the creation in 1919 of the National Catholic Welfare Council, which involved itself at the federal, state, and local levels of Catholic activity regarding legislation, education, publicity, and social action.

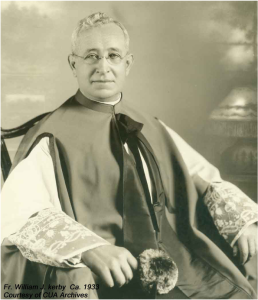

Monsignor William Kerby, a professor of sociology at Catholic University, was a huge advocate of the Catholic need to establish organizations parallel to those Protestant. He worried about “leakage” of professionals and intellectuals from the church into secular or Protestant society. He noted that America was a pluralistic society that offered a host of organizations competing for allegiances, but an indifference to religion might develop within such organizations. Establishing specifically Catholic versions would counter the development of this indifference, in Kerby’s view.

In 1919, the bishops met as an assembly to discuss the creation of a National Catholic Welfare Council. This was representative of the whole of the Catholic bishops. But not all bishops were on board, as they thought it might interfere with their diocesan prerogatives.

At that time, they established an administrative committee of 7 bishops, later expanded to 10, elected annually. The committee met periodically through the year, and operated a 5 branch Secretariat.

This Secretariat was initially run by Father Burke, who served as the General Secretary. Its functions were to oversee:

* An Immigration Bureau and Motion Picture Bureau to offer technical assistance to immigrants at ports of entry, and promote decency in the movie industry.

* A Social Action Department. This promoted Catholic views of civic education, industrial relations, and rural welfare through publications and speakers.

* A Department of Education that informed the public on Catholic education and dealt with educational matters, which were actually in ferment at the time, as there were many attempts to abolish parochial schools.

* A Legal Department to study state and federal legislation with a view to either removing anti-Catholic aspects, or making the Catholic position known.

* A Press Department provided subscribing newspapers, such as Catholic diocesan newspapers with a weekly set of articles covering national and international events from the Catholic angle.

* The Department of Lay Activities organized Catholic people across the country into the National Conference of Catholic Women (NCCW) and National Conference of Catholic Men (NCCM).

At this point, however, there was a problem with the emerging organization that illustrates its uniqueness. One of the members of the hierarchy, Cardinal William O’Connell of Boston, did not like this new organization. He and several bishops feared that it would impinge on their local authority. Though O’Connell temporarily stalled the evolution of the organization, by 1922 a clarification in the name entailing a shift from the word “council” to “conference” satisfied the authorities involved, and the name was changed to the National Catholic Welfare Conference. The organization had another name change and reorganization in the 1960s, and as of 2001, it has been known as the US Conference of Catholic Bishops.

From 1922 through to the 1960s, this organization addressed a range of matters related to American Catholic life. A few examples of their influential work:

Catholic Social Justice. Just after the war, the Bishops’ Conference issued the Bishops Program for Social Reconstruction (1919). This was a plan for social reform written by Father John A. Ryan, a professor of Sacred Theology at Catholic University. Combining Progressive thought and Catholic theology, Ryan believed that government intervention was the most effective means of affecting positive change for his church as well as working people and the poor. The program advocated minimum wage legislation, the elimination of child labor, state-run insurance for the sick, unemployed, and elderly, and housing for returning veterans, among other things. Labeled “socialistic” by its critics in the 1920s, much of the Program was implemented during the New Deal years.

Monsignor Ryan himself was appointed the head of the NCWC’s Department of Social Action (or SAD). This department employed staff to travel the country and educate Americans on how Catholic social teaching spoke to industrial matters, living wage issues, and other economic and social issues. The Social Action Department became a kind of national Catholic information clearing house on matters of Catholic social justice as applied to American life.

Catholic Education. You may or may not know that the 1920s saw a national upswing in anti-Catholic activity. The KKK, for example, had millions of members and, in addition to being anti-Black, they focused their hate on Catholics and Jews. The KKK and other groups of anti-Catholics sought to abolish Catholic parochial schools in many states. The Education Department raised funds, hired lawyers, and mediated such cases successfully in the 1920s, ensuring that parochial schools could exist.

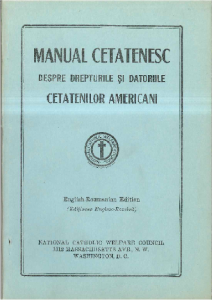

Immigration and Americanization. As you might imagine, the church was very interested in the immigrant population. By 1920, there were about 20 million Catholics in a total U.S. population of just over 106 million. Many of these were immigrants and the children of immigrants–over 3.5 million Catholics migrated to the United States between 1900 and 1920. Catholic immigrants created communities that differed considerably from the established Anglo-Protestant pattern. Few spoke English, and many were impoverished working-class laborers. Immigrants tended to congregate in urban areas with others from their country of origin, creating ethnic neighborhoods in the cities. These neighborhoods were shunned by the Protestant majority, who viewed them as breeding grounds for illiteracy, disease, immorality, and un-Americanism. The Catholicism practiced in these ethnic communities also drew suspicion, as it looked very different from the practices established by earlier Catholic settlers in the U.S. These immigrant Catholics focused on creating vibrant parish networks built around ethnic group identification.

Priests and religious orders were brought from European countries to minister to the new parishes. As these ethnic communities grew, churches, schools, charitable organizations, newspapers, hospitals, and other institutions sprouted around them. For example, in 1880, there were 2,246 parochial elementary schools with 405,234 students in the U.S.; by 1910 there were 4,845 parochial elementary schools and 1,237,251 students. A Department of Immigration was soon established to address issues related directly to immigration as well.

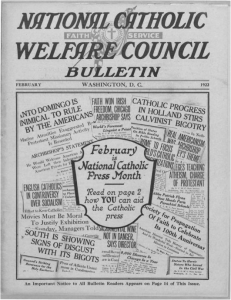

Media and popular culture. The NCWC established a Press Department specifically devoted to Catholic information.

Established in 1920, the National Catholic Welfare Council (NCWC) Press Department provided the Catholic press, radio, and eventually television in the United States and other countries with news, editorial, features, and picture services prepared by professional journalists and released under the names NCWC News Service. Most dioceses had their own newspapers, focused on local Catholic affairs. But the NCWC Press Department covered issues of national significance, which the local papers ran as subscribers. This meant that Catholics could tell their own stories about themselves, rather than simply absorbing a Protestant dominated narrative. Hence, this organization helps generate a national Catholic and American identity.

The national idea is crucial here. There was no national and Catholic institution in existence that covered so many different facets of American life, prior to the establishment of the NCWC. And its creation was a product of the church’s adaptation to democratic life, with political institutions that required participation and advocacy of one’s view in a pluralistic society to survive.

Sources:

Douglas J. Slawson, The Foundation and First Decade of the National Catholic Welfare Conference (Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University Press, 1992).

Elizabeth McKeown, “The ‘National Idea’ in the History of the American Episcopal Conference,” in Thomas J. Reese, S.J., Editor, Episcopal Conferences; Historical, Canonical & Theological Studies (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press).

Online resources:

A Finding Aid to the Records of the NCWC/USCCB

The U.S. Bishops and Immigration, an Online Exhibit

The U.S. Bishops and the Program of Social Reconstruction of 1919

The National Catholic War Council Digital Collection

Blogpost: For God and Country: American Catholics in the First World War