In his landmark 1990 scholarly work, The History of Black Catholics in the United States, Cyprian Davis presents a deeply researched history of African American Catholics in the United States. He proved that, while Black Catholics seemed invisible across U.S. Catholic history, in fact, the American Church has never been exclusively a white and European one. In fact, as he writes, “the African presence has influenced the Catholic church in every period of its history.” He concludes that for “[t]oo long have black Catholics been anonymous. It is clear they can be identified, that their presence has made an impact, and that their contributions have made Catholicism a unique and stronger body.”[1] In that spirit, we offer an overview of some of our richest materials related to the Black Catholic experience in the United States, including the papers of Father Cyprian Davis himself.

In 2015, Special Collections acquired the papers of Father Cyprian Davis. Davis, born Clarence John Davis (1930-2015) in Washington, D.C., was a historian and archivist. A convert to Catholicism in his teenage years, Davis expressed an early interest in the priesthood. He joined the seminary of St. Meinrad Archabbey in Indiana, where he became a novice in 1950, and took the monastic name Cyprian in 1951. Ordained a priest on May 3, 1956, Davis became the first African American to join the monastic community of St. Meinrad.

He began his academic career in 1948, studying at The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. where he received a Licentiate of Sacred Theology in 1957. Davis then studied church history abroad at The Catholic University of Louvain, Belgium, where he obtained a licentiate in 1963. He taught church history at St. Meinrad before returning to Louvain for his doctorate degree in 1977. Father Davis authored and co-authored several pioneering monographs, including Christ’s image in Black: The Black Catholic community before the Civil War and The History of Black Catholics in the United States. Davis’s papers include many unpublished manuscripts on Black history and Black Catholic history, as well as correspondence, academic papers, printed material, audiovisual records, ephemera, and a range of awards and honors. A finding aid for the Cyprian Davis papers can be found here.

For insights into how white Catholics sought to promote interracial activities within the Catholic Church in the first half of the twentieth century, researchers can consult the records of the Catholic Interracial Council of New York (CICNY). Father John LaFarge, S.J., founded the CICNY in 1934 to promote mutual understanding and social justice among Blacks and whites. The CICNY disseminated information and held meetings and conferences on Catholic teaching and race. Through the 1940s, the CICNY addressed issues such as the Scottsboro Boys’ case, lynching, communism, and efforts to open the defense industry to Black workers. They also regularly honored Catholic civil rights activists with a number of annual awards and celebrations, including the annual John A. Hoey Interracial Justice Award. The idea of interracial councils led to their formation in Chicago, Detroit, St. Louis, and Washington, D.C. By 1954, 24 Catholic Interracial Councils had been created.

The CICNY continued well into the 1990s, but had declined markedly in activity and importance by the late 1970s. The Interracial Review, of full set of which can be found in the voluminous CICNY Records, one of its more important undertakings since its founding, ceased publication in 1966, although it was revived in a much less ambitious format in the 1970s. Several civil rights leaders, including A. Philip Randolph and Roy Wilkins, contributed to the journal. A finding aid for the CICNY can be found here.

Washington, D.C.- Related Collections

The Haynes-Lofton Family Papers are comprised of the personal papers of Catholic University of America alumna Euphemia Lofton Haynes, her husband Harold Appo Haynes, and their families. A native Washingtonian, Euphemia Lofton Haynes (1890-1980) received a Bachelor’s Degree in Psychology from Smith College in 1914, a Master’s in Education from the University of Chicago in 1930, and a Doctorate in Mathematics from Catholic University in 1943, making her the first African American woman to receive a Ph.D. in Mathematics in the United States. She taught in the public schools of Washington, D.C. for 47 years and was the first woman to chair the D.C. School Board. She figured prominently in the integration of both the D.C. public schools and the Archdiocesan Council of Catholic Women. The papers consist of correspondence, financial records, publications, speeches, reports, newspaper clippings, and photographs, and provide a record of her family, professional, and social life, including her involvement in education, civic affairs, real estate, and business matters in Washington. A finding aid for the Haynes-Lofton family papers can be found here.

Educator and activist Paul Philips Cooke (1917-2010), a member of Washington D.C.’s Sacred Heart parish, lived most of his long life in the District. After earning a Master’s in English Literature from The Catholic University of America in 1942, and a Doctorate in Education from Columbia University in 1947, Cooke taught and served as president of the District of Columbia Teachers College until 1974. He was an active member of the Catholic Interracial Council of the District of Columbia (CIC DC) for over 50 years. The collection includes correspondence, clippings, reports, meeting minutes, photos, pamphlets, and publications. A finding aid for the Paul Philips Cooke papers can be found here.

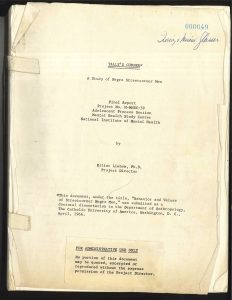

For more on African American life in Washington, D.C. in the second half of the twentieth century, researchers may also consult the Elliot Liebow Papers. Liebow (1925–1994) was an American anthropologist, best known for his 1967 book Tally’s Corner: A Study of Negro Streetcorner Men, a study of Black men in urban Washington, D.C. The book, based on his 1966 Catholic University of America Department of Anthropology doctoral dissertation “Behavior and Values of Streetcorner Negro Men” sold nearly a million copies, and though dated today in its methodology, was influential in its time. Beginning in 1990, he held the Patrick Cardinal O’Boyle Professorship at the National Catholic School for Social Service of the Catholic University of America. He died in 1994. Series 3 of the Liebow papers contains research material related to Tally’s Corner. Although some of the research material is subject to a 60-year restriction in order to protect the identities of the case study participants, the open material includes the original manuscript of Tally’s Corner, correspondence about the book, book reviews, and publicity material (e.g., ads and ephemera). A finding aid for the Liebow papers is currently underway and should be completed by early 2021. In the meantime, please contact the archives staff directly at lib-archives@cua.edu or 202-319-5065 for more information.

Education Resource Websites

The Thomas Wyatt Turner and The Federated Colored Catholics website is one of our most well-used educational resources. The site revolves around Turner’s struggle to promote racial equality in the U.S. Catholic Church. In that struggle, we see how even people of good faith have often disagreed over the best strategies for winning the battle. Some have argued that African-Americans or other racial minorities have needed the chance to unite, gain power, and win respect from white majorities. Others have contended that convincing white, and indeed all Americans, to be colorblind—to not “see” race—has been the best plan. Such disagreements emerged among American Catholics in the 1920s and 1930s in debates between Dr. Thomas Wyatt Turner, an African-American layman, and Father John LaFarge, a white Jesuit and long time civil rights advocate. The Thomas Wyatt Turner and the Federated Colored Catholics website can be found here.

The Catholic Church, Bishops and Race in the Mid-Twentieth Century website features resources and documents related to the U.S. Catholic Bishops in the mid-twentieth century. While battles were waged against racist institutions in America in the decades prior, it was the 1940s–1960s that set the tone for the momentous changes in the history of African Americans. Often termed the “Second American Revolution,” the Civil Rights Movement of those decades sought the end of segregation across a wide swath of American society, including schools and other public organizations. The Catholic Church in the U.S. saw the struggle for equality within its own walls, and many church leaders were determined to not only free their institutions from segregation, but to work for its demise in the general population as well. While recognition of the Church’s work in civil rights has paled in comparison to the luminaries of the movement, several individuals and organizations made a mark nonetheless, overcoming resistance at times from within their own parishes and institutions. The website can be found here.

In the 1930s and 1940s, comic books were one of the most popular forms of entertainment among the nation’s youth, combining as they did narratives, graphics, and low prices. Concerned over the possibility of the effects of such entertainment on the moral character of young people, the Commission on American Citizenship at The Catholic University of America worked with George A. Pflaum of Dayton, Ohio, to publishing a bi-monthly comic book, the Treasure Chest of Fun & Fact for distribution in Catholic Parochial Schools starting in 1946. The Treasure Chest was intended as a remedy to the sensationalism of traditional comics: it contained educational features, narrated the lives of saints, and presented adventure stories featuring realistic characters with what were considered wholesome values, like patriotism, equality, faith, and anti-communism.

By the early 1960s, the Treasure Chest was at the height of its popularity. In 1964, Joe Sinnott, the illustrator of Marvel Comics’ “The Fantastic Four,” teamed up with writer Berry Reece to produce a story depicting a U.S. presidential election. It was set in the future: the presidential election was supposedly that of 1976, the year of the nation’s bicentennial. “Pettigrew for President” lasted for 10 issues, following the campaign trail of the fictional Tim Pettigrew from the announcement of his candidacy through the national convention of his party. The candidate’s face was carefully hidden in every panel, until the final page of the final issue of the story, when Pettigrew is finally revealed: the first Black candidate for president of the United States! This site reproduces the entire “Pettigrew for President” series in a digital format. It places this unique comic book story in the context of the 1960s civil rights movement, and provides background information on the creators of the series. The website can be found here.

For more on these materials and more see our newly-created LibGuide on African American History-Related Collections.

[1] Cyprian Davis, The History of Black Catholics in the United States (New York: Crossroad, 1990), 259.

One thought on “The Archivist’s Nook: African American History-Related Collections”