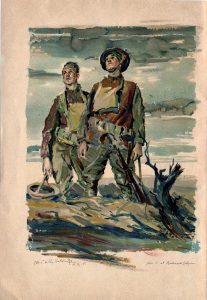

As part of our ongoing efforts to mark the centenary of the First World War a previous blog post explored the 1917 experiences of Connecticut Catholic Robert Lincoln O’Connell training as a combat engineer in Washington, D.C. This is documented by the collection of digitized letters to his mother and sisters housed in the Archives of The Catholic University of America. Now we turn to his 1918 accounts of the war as O’Connell and his unit, the First Engineer Regiment, part of the famed First Infantry Division and vanguard of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) in Europe, saw harrowing service on the Western Front in France during the war’s culmination. To complete their military instruction, which began in Washington, O’Connell and the First Engineers were trained by the French in the construction of trenches, dugouts, command posts, heavy weapons sites, observation posts, wire entanglements, and other obstacles. They also learned to destroy enemy fences by cutting wire or using explosives. In addition, they drilled as regular infantry in the use of rifles, hand grenades, and gas masks.

The First Engineers served near Toul, January-April 1918, where they quarried rock, repaired roads, built dugouts, command posts, and wire entanglements while often being shelled and gassed as they worked. American efforts to strengthen the positions in Cantigny, where the engineers served, April-July 1918, helped the French thwart a German offensive. To contain yet another German attack, the First Infantry Division shifted to the Aisne-Marne sector, with the engineers deployed to the Compiegne forest where O’Connell was wounded on July 18. The engineers not only overcame natural obstacles, but fought in the front line and suffered many casualties, O’Connell among them. During his rest and recuperation, he missed the fighting in the St. Mihiel Salient, but after recovering returned to service in the Meuse-Argonne campaign in October and was there when the war ended on November 11, 1918.

The O’Connell collection includes fourteen of his often breezy letters and eleven postcards sent home from France. In his March 18, 1918 missive to his mother he noted:

I am writing each week now because I have my own paper, in case I haven’t a chance to reach a Y.M.C.A. tent or an S.A. but there are few places that those people haven’t opened buildings. In this village, the two huts face each other, across the street, but the Y.M. draws the crowd and the money because they have a better equipped place. A real band has been around town for the last week and the way they grind out ragtime is a treat…Yesterday was Patrick’s day but only one man had any green and that was a scrap of weed in his buttonhole, that he had brought back from the trenches. He seemed to be the only good Irisher in sight.

In the same letter he muses about his enlistment and service:

This letter will probably reach you about the end of my first year in the Army. If you remember, it was Apr. 10, when I went up to Hartford to see if they would pass me. It has been a short but lively year and I hope I get home before another passes but I’m glad I got in early because the drafted crowd certainly didn’t have places like Washington Barracks to train in or warm weather, either, but they will have the laugh on us when they get over here and find things cleaned up.

O’Connell was wounded in action on July 18, 1918, as he explained in his July 24 letter to his mother:

There was a little round hole in my leggin, at the sore spot, so I took my rifle and started back for the dressing station, about half a mile away. It was just an emergency station, though, and they told us to keep going, to a larger place in a big cave. There was five in the party, by now, either limping or nursing a bad arm and that cave was almost two miles farther along. I’d have walked twenty, I think, to get some relief from those shells….When you get this, I’ll be back with the company again, but I’ll have had this rest, anyway, just for a little hole less than half an inch deep.

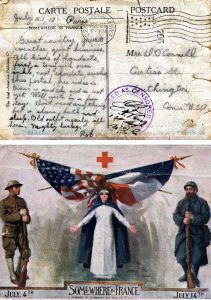

He apparently downplayed his injury for his mother’s sake because he did not return to active duty until October, demonstrated in several later letters and postcards, such as his postcard of September 27 to his mother where he said:

Ought to be back with the boys in a week or so, Leaving the barracks at this place. A few of the boys are here after the St. Michael drive. No mail since early in July. Guess never will get it all. Have had a fine rest. Seems as if all the original company had been resting. Wish this darned war was over. I want to see what is going on at home.

And, finally, his postcard of October 15 announcing his return to his unit, plus additional commentary:

Got back to the company about a week ago. Received four letters, one from you, and from Mame and Helen. Better than money. Paid last in June. Did you receive the $20 from the YMCA and the piece of German airplane cover? I don’t need any money. I can send it, instead. Hope all are well. Good news in the papers, lately.

The war ended on November 11, 1918, and the First Engineers arrived in Germany’s Rhineland shortly thereafter as part of the army of occupation, but that is another story for a future blog post. O’Connell’s wartime experiences are a well preserved and freely available testament at Catholic University that give voice to the millions of soldiers of all nations whose accounts have not survived.