This week’s post is guest-authored by Michaela Granger, a graduate student in History at Catholic University.

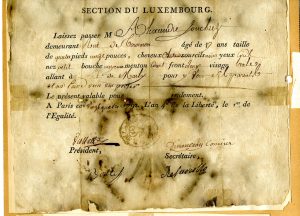

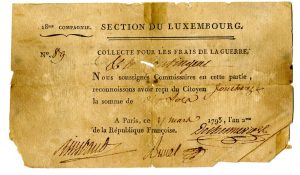

Age: 17. Height: 4 feet, 11 inches. Nose: small. Forehead: large. The above description belongs to a certain Alexander Louis Joncherez, a young man who came of age the same year as the Première République of France. This particular document was issued the “the fourth year of liberty, and the first year of equality,” otherwise known as 1792. In September of the next year, mere days after the ‘Reign of Terror’ had begun, officials in the District of Montivilliers recorded that Joncherez was now 18 and had grown to 5’ 1’’. They also gave him permission to travel. Joncherez took advantage of this freedom and eventually arrived in the newly established United States. In 1798 a clerk of Prince George’s County, Maryland, recorded that Joncherez had officially been naturalized as a citizen of his adopted nation. How do we happen to know these details about a relatively obscure French-American who lived over two-hundred years ago? The eleven documents which provide this information are part of the American Catholic Research Center’s Iturbide-Kearney Family collection.

In many ways, the story told by these documents raise more questions than they provide answers. In order to highlight both this fascinating collection and the process of historical inquiry, the rest of this post will be dedicated to considering some of the most interesting questions surrounding Joncherez’s papers. Perhaps the best question to begin with is “why did Joncherez keep these papers?” During the French Revolution, the possession of a valid passport could often mean the difference between life and death. French citizens who left during the Revolutionary period were called émigrés, a term that connoted a certain degree of disloyalty to the Republic. Fearful that these émigrés were plotting to overthrow the new government from their places of exile, the Revolutionary government began passing new legislation in 1792. Any émigré who attempted to return to France after this date had to prove they were given permission to leave and had remained loyal to the Republic during their absence. If they were unable to do so, they were liable to be executed as traitors. In light of this, the fact that Joncherez kept these documents suggests he had some intention of returning. If he had wished to completely sever his ties with his natal country, there would have been no need to keep these eleven documents (which include not only several passports, but documents confirming he paid the war tax, had taken an oath of allegiance to the Republic, and provided compulsory military service).

Did Joncherez hope to return to France? Or did he keep the documents purely for sentimental value? If he ultimately hoped to return, why did he leave in the first place? Did he ideologically support the Revolution? Or did he simply pretend to as a survival strategy? What did his French citizenship mean to him? Another set of fascinating questions relate to Joncherez’s ultimate destination: the United States. Why did he choose to come to the United States? The overwhelming majority of French émigrés migrated to England, estimates suggest close to 12,500 per year. There were at least 7,400 members of the French clergy alone in England by 1792. Why didn’t Joncherez go to England? It does not seem likely that Joncherez had family in the United States, but it is not impossible that he could have had other networks which drew him here. If it was not relationships, could he have been drawn to the United States for ideological or religious reasons? A few other notable French émigrés settled in Maryland, for example Father John Dubois, founder of Mount St. Mary’s University. However, Joncherez wasn’t a member of the clergy. Could Joncherez, like Pierre Charles L’Enfant and Marquis de Lafayette, have been attracted to America’s Revolutionary spirit?

Finally, why did Joncherez choose to stay? When Napoleon Bonaparte granted amnesty to the majority of émigrés in 1802, a sizeable number of them returned to France. Why not Joncherez? We do know he married a certain Nancy Sanford of Virginia, although it is not clear when. Could he have stayed for love? If it was not a traditional romance that influenced his plans, is it possible that by this point Joncherez had fallen in love with his adopted home and the life he had created here? Additional research has revealed that Joncherez quickly made himself a productive and active member of early American society. He served on the jury of the U.S. Circuit Court of the District of Columbia twice in 1809. He exchanged property with Edgar Patterson in 1811 and Benjamin MacKale in 1817. He exchanged two letters with Thomas Jefferson regarding the donation of several maps in the summer of 1812. He registered as a private in ‘Irwin’s company,’ part of the District of Columbia’s Militia, during the Creek War (1813-1814). There is some evidence that he taught French at Georgetown University and was a member of the local chapter of Freemasons. He had children, and grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. In fact, one of these great-grandchildren, Louise Kearney, happened to marry an exiled Mexican prince and pass on the documentary testament of Joncherez’s life to the Catholic University Archives. My hope is that this post may inspire some to visit these holdings for themselves in search of even more answers.