“The need of the Catholic Social worker no one will question. There should be no question of the need of the TRAINED social worker. Social Service is today a PROFESSION. Motive and intention can inspire—but without KNOWLEDGE they can never achieve.”

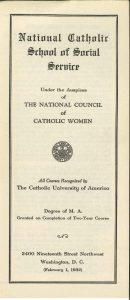

National Catholic School of Social Service pamphlet, 1932

In researching the history of the National Catholic School of Social Service at Catholic University (NCSSS), I came across a pamphlet, from which the above quote jumped out at me. The words “trained,” “profession,” and “knowledge” were all capitalized, as if to emphasize that those who performed in the social work field required these elements of preparation in order to practice their work properly. Today, of course, we know this to be true, as do the many students and faculty who form the University’s prestigious school of social service. But in 1932, social work was just coming into its own as a profession. The earliest settlement houses were founded in New York and Chicago in the late nineteenth century to address the problems of poverty engendered during the Industrial revolution. By 1913, there were hundreds of settlement houses across the United States toward addressing social problems. But the question of training individuals as professional social workers was still being hashed out. When, Dr. Abraham Flexner claimed in 1915 that social work was not a “profession because it lacked specific application of theoretical knowledge to solving human issues,” the professionalization of social work began in earnest. Catholic University’s NCSSS is an important part of that history of professionalization.

The advent of the U.S. involvement in the First World War in 1917 saw large scale mobilization of a variety of social groups toward addressing wartime problems, Catholics among them. The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops organized specifically to address wartime needs of Catholics. They immediately realized that wartime workers—especially women who served to provide services to soldiers and those dislocated by war—needed training to perform effectively both overseas and stateside. The origins of NCSSS lay in the training of women for war and reconstruction efforts both at home and abroad. It would have been simple to train these women on the campus of Catholic University here in Washington, D.C., but the University still did not admit women in 1918, when it was decided by the U.S. Bishops that a training school for wartime social service would be created. So “Clifton” was established through the efforts of Fathers John J. Burke and William Kerby in 1918 in the Georgetown Heights area of Washington, D.C. for this purpose. Run by the National Council of Catholic Women, the school’s first dean/director was Maud Romana Cavanaugh, an ambitious and energetic woman who managed to open the school on November 25, 1918. Cavanaugh served as early faculty, along with Catholic University faculty members, such as Father John Ryan, Father John O’Grady, and Father Kerby, all well-known for adapting Catholic teaching to American social problems. The earliest classes included “Catholic Principles in Social Work,” “Relief of Poverty,” and “Public Health.” Kerby, in particular, worked on creating a body of teaching and thought that wove the emerging theory in social service with Catholic social thought.[1]

It became clear that the school would have to move, as the Clifton lease was running out, and the location was nearly two miles from any transportation line, making travel to and from the house difficult. A second site was found by Father Burke and faculty member Agnes Regan in the Mount Pleasant section of Washington, D.C., and the new National Catholic School of Social Service was established there in 1921. With the move, the brief training sessions at Clifton were replaced with a two year graduate program in social work. Under the directorship of Anne Nicholson, a curriculum review took place and a standardized course was developed for the school. After NCSSS was admitted to the American Association of Schools of Social Work, enrollment began to rise.[2]

Keep in mind that the students lived at the school. This was by design: faculty believed that the students would develop a deeper sense of community if they resided in the same house. These years were especially festive and sought to be inclusive toward the broader community. At Christmas, for example, the students held a party for dozens of children from local institutions, many from where the students had done their field work. The parties featured and afternoon of games, candy, toys, and a visit from Santa Claus. Groups of students often gathered around the parlor piano and sang. Teas, picnics, and barbecues were common. Guests were almost always present for Sunday evening candle-light suppers, and the school was known for its delicious and nutritious food. The faculty at the time, Agnes Regan, Fathers John Ryan and John Burke, loved to gather and play bridge in the evenings.[3]

NCSSS held a formal connection to Catholic University’s graduate school, and students received their degrees from the University, but by the late 1930s, the connection became more explicit. A separate School of Social Service was established at Catholic University in 1934 for priests, religious and lay men. Laywomen were admitted into the University’s graduate programs in 1930. This resulted in a revamping of the school’s policies that ultimately integrated the administration and degree-awarding structure of NCSSS into the broader University academic policies. While the two programs in social work ran parallel for a number of years, conferring slightly different degrees to its graduates, in 1939 NCSSS merged with Catholic University’s School of Social Service. From that year forward, graduates of the program received the same degrees. Though the two entities remained physically separate for several more years, in 1947, they merged and took the name of the National Catholic School of Social Service. NCSSS found its new and current physical home in Bishop Shahan Hall, which was dedicated in 1950.

__________

[1] Loretto Lawler, Full Circle: The Story of the National Catholic School of Social Service (Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1951), 17-24.

[2] Lawler, Full Circle, 57-69.

[3] Lawler, Full Circle, 81-89.