The year 1919 could be termed a grim one. The First World War had ended in November, 1918, true, but the combatants were still taking measure of that frightful conflict. With more than 70 million people mobilized to fight, more than 16 million had died as a direct result of the war, with another 50 to 100 million dying as a result of the 1918 influenza pandemic. A “Red Scare” gripped the United States, as fear of communist agitation rippled through the country in the wake of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

These more immediate happenings occurred in the context of long term changes in social and economic life that had accelerated during the previous century. The industrial revolutions transformed the nature of work, the landscape of cities, and the lives of peoples displaced by the changing economy. Pope Leo XIII had addressed the meaning of such changes for Catholics in his 1891 encyclical Rerum Novarum, noting that “new developments industry, new techniques striking out on new paths, changed relations of employer and employee” had led to “a decline of morals and caused conflict to break forth.” Many Catholics in the United States and elsewhere sought to address how their religion might address social and economic transformation.[1]

When the National Catholic War Council led by the United States bishops formed in 1917, their chief aim was to assist the millions of Catholics mobilizing for the First World War. However, when the war ended it became clear that a national Catholic organization designed to coordinate activities among the nation’s faithful would prove useful. In 1919 the bishops changed the name of their young organization to the National Catholic Welfare Council and began discussing a Catholic plan for postwar America.[2]

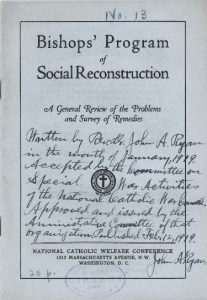

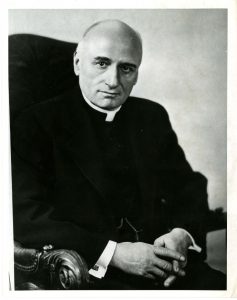

The National Catholic War Council, like many social and religious groups of the time, was eager to offer a Catholic plan for postwar America of its own. In April of 1918 the bishops established a Committee for Reconstruction. The war ended on November 11, 1918, however, sooner than the Committee could forge their plan. The Committee’s secretary, Catholic charity expert Rev. John O’Grady had only the vaguest notions of what its plan should look like at that time. O’Grady, panicking in early December because he needed a plan immediately, turned to Father John A. Ryan, who had written a book on living wage issues and studied social reform extensively, to write a program. Ryan at first resisted then agreed and dictated the Program to a typist two days later. Ryan’s program was pushed quickly through the administrative structure of the War Council and approved by the Committee’s bishops. The program called for government insurance for the sick, unemployed and aged; labor’s participation in industrial management; public housing; unions’ right to organize, and a “living wage” for all workers. The Program’s publicist, Larkin Mead, set a release date for it: February 12, 1919, Abraham Lincoln’s birthday.

The Program was called then, and forever after would be called, the “Bishops’ Program for Social Reconstruction,” the implication being that it represented the entire church’s views on the remaking of America in the postwar era. That claim was disputed by some, because the War Council’s authority to issue such a sweeping statement on behalf of the whole church was questioned. Some Catholic prelates and business groups opposed the bishops’ plan on the grounds that it was too radical. William Cardinal O’Connell of Boston, for example, believed some aspects of the plan were “socialistic,” a word often used to describe what was viewed as too much government involvement in American society and the economy. Many Americans were inclined to share O’Connell’s suspicions; the Red Scare in particular heightened fears of “Bolshevik” plots. As the 1920s progressed, Americans’ lost their appetite for Progressive reform, and critics of the Bishops’ plan gained traction. The kind of reformism advised in the Bishops’ Program would not find an audience again until the economy slid into the Depression in the 1930s.

Read the entire Bishops’ Program for Social Reconstruction here

Visit the website related to the Bishops’ Program for Social Reconstruction here

A finding aid to the National Catholic War Council can be found here

A finding aid to the papers of John A. Ryan can be found here

_____________________________________________________

[1] Quote from Rerum Novarum is on the American Catholic History Classroom website, Catholic and Social Welfare, 1919: https://cuomeka.wrlc.org/exhibits/show/bishops/bishops/1919bishops-intro2.

[2] “Council” would be changed to “Conference” in 1922, with the organization serving as the forerunner of today’s United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.