This semester I had the pleasure of processing the Cecilia Parker Woodson Collection, a set of papers donated to the Archives by Tierney O’Neil via Robert Andrews last year. We call this a collection, by the way, because these are not a full set of papers related to Cecilia Woodson, rather, they are a set of materials she, deceased 79 years now, curated herself.

Did I write Cecilia Parker Woodson? I meant to write Cecil. Cecil was what her husband, Walter, and all of her friends called her, because that is what she wanted to be called. And now, after reading the hundreds of letters written to her between 1891 and 1920, I feel like I know her too, though she died decades before I was born. The first set of letters Cecil saved were the love letters sent to her by her traveling salesman husband Walter, and they offer a wonderful window into late nineteenth century courtship practices and social life in their native Virginia and Washington, D.C.

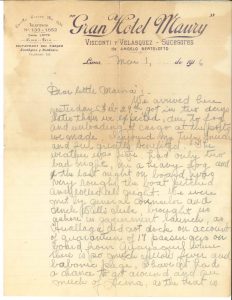

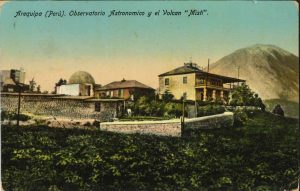

One thing I would not call Cecil is “Dear Little Mama,” though most of the letters addressed to her in this collection open with just that salutation. The most voluminous correspondence in these collected papers are from Cecil’s daughter, Charlotte “Lottie” Virginia Woodson. Lottie left the family nest over on Monroe Street here in Brookland for Lima, Peru at the age of twenty-one. Cecil’s best friend Mary and her husband William Montavon, better known to Lottie as Aunt Mayme and Uncle Will, asked Cecil and Walter if they could take Lottie to Lima when Uncle Will was assigned a two-year diplomatic post there in 1916. Lottie was terribly eager to take the trip, and sailed off from New York City to Lima in February of that year. Her letters home chronicle the life of a young woman living in the foreign diplomatic set just before and during the First World War. There were teas, dinners, dances and decisions about the most appropriate footwear for the occasion, and Lottie writes “Dear Little Mama” about all of it. She even coyly describes her own courtship with another young diplomat, Victor Louis Tyree, who happened to also hail from Washington, D.C. The two were married in 1918 in Lima and made plans to move to La Paz, Bolivia afterward, when Victor was offered a better paying job with Denniston and Company after their marriage.

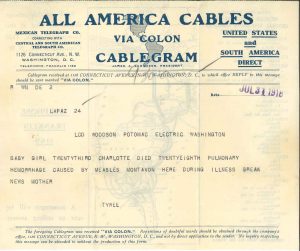

Dear reader, this story does not end well. I’ll admit that I teared up when I read the telegram dated July 31, 1918: “BABY GIRL TWENTY THIRD CHARLOTTE DIED TWENTY EIGHT PULMONARY HEMORRHAGE CAUSED BY MEASLES.” Charlotte was pregnant soon after her marriage and she died in La Paz, just after giving birth to Merle Virginia Tyree. Not a week later, baby Merle died as well. Victor writes a long letter to Cecil describing the birth and death in heartbreaking detail. The letter had been read so many times it is falling apart. After a handful of condolence letters, Cecil’s collection of correspondence pretty much ends, as if she just didn’t have the heart to save any more letters, or perhaps she received so few after that it didn’t seem worth it. She lived twenty-two more years, however, dying in 1940 at the age of 76.

Cecil saved the letters others wrote her, and she saved many beautiful photos of her family, as well as those Lottie sent her from Peru. But there is only one letter handwritten by the collector herself. And it appears to be a draft of a note she was going to send to her daughter to congratulate her on her engagement. “How can I relinquish my claim on you my own darling little girlie?,” she writes, “God bless you both and if your lives are spared, may you both in the years to come be as happy in each other as now.” There isn’t even a photograph of Cecil herself in the collection. Still, the strength and generosity of the woman emerge in the letters written to her and her life was a full one, tragedies and all.

You can view the finding aid to the Cecilia Parker Woodson Collection here:

http://archives.lib.cua.edu/findingaid/woodson.cfm

You can view the finding aid for the papers of William Montavon here: