Robert Lincoln O’Connell (1888-1972), a World War I Connecticut army engineer of Irish-Catholic heritage, was the subject of two of my previous blog posts. They explored his letters home to family while training for the military in Washington in 1917, and his active service on the western Front in France in 1918. The third and concluding post of this trilogy looks at his experiences in the U.S Army’s brief postwar occupation of the Rhineland, as well as victory parades in New York and Washington in 1919. As with previous letters, they are written by “Rob” primarily to his mother and his sisters, Ellen and Sarah, who lived in their hometown of Southington, Connecticut. O’Connell’s archival papers, which have also been digitized, are housed in the Special Collections of The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C.

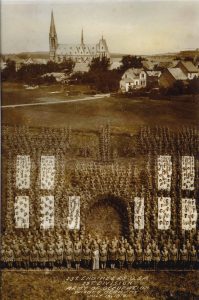

O’Connell served in the U. S. Army of Occupation in postwar Germany. His First Engineer Regiment was part of the First Infantry Division (later immortalized in the Second World War as ‘The Big Red One’). They crossed the Moselle River into Germany on December 1, 1918, and arrived at Coblenz, along the Rhine River, on December 12. During the occupation, which lasted until August 15, 1919, the engineers constructed shelters, improved sanitation, built pontoon bridges, and repaired roads. With ample recreation time, O’Connell engaged in hiking and sightseeing tours where he collected many colorful postcards. In one letter home he wrote(1):

“It took about an hour to reach the river near Coblenz” and “the place was crowded with 2nd Division men, mostly Marines, it seemed, and one of them threw a snowball into our truck. As we were jammed in and had no top, that ball couldn’t miss and we could only yell back, which started a barrage of snowballs…. I got one on the ear and we all had snow down our necks. I didn’t care much for the game because the mud made the ball slippery– and the 1st Division team needed a lot of practice. The score was 6 to 0 in favor of the second team.”

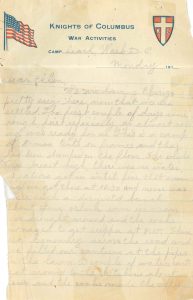

Unlike the aftermath of World War II, the U.S occupation of German territory in 1919 was short lived. O’Connell returned stateside with main elements of the First Infantry Division at Brest on August 18, and arrived at Camp Mills, New York, on August 30. He took part in victory parades in both New York City on September 10 and in Washington on September 17. The final (undated) letter in the collection, addressed to his sister Ellen from Camp Leach, part of the campus of American University in Washington, was probably written a few days after the parade in New York (2):

“This is a camp of 8-man tents on frames and they had been dumped on the floor…We got there at 10:30 and never was there such a disgusted bunch. About four o’clock some ice cream was brought around and the cook managed to get supper at 8:15…Now we are getting plenty of good eats and passes into town 7 c carfare and the K of Cs especially are doing all they can, lots of cigarettes, matches, hand kerchiefs, sightseeing trips around the city in busses and free beds. The papers and the posters rave about the famous or glorious First Division and the recruiting officers are making the most of it.”

The campus of American University was also the base of the Army’s Chemical Warfare Unit, which also had a sub-unit at nearby Catholic University. These facilities developed deadly chemical munitions, especially Lewisite Gas. This weapon of mass destruction was invented by C.U. student-priest Julius Nieuwland, though it was not ready in time for use during World War I. However, O’Connell’s visit to Washington had nothing to do with poison gas. It was his final military march. The soldiers paraded to great ovation from the Capitol along Pennsylvania Avenue. Marching past the White House, they were reviewed by the Vice President and members of the Cabinet, who were representing President Woodrow Wilson, while he was away canvassing the country on a doomed mission to sell ratification of the Versailles Peace Treaty. From Washington, the men were shipped to Camp Meade, Maryland, where many were demobilized. O’Connell went on to Camp Devens, Massachusetts, where he was mustered out on September 27, 1919.

After the war, O’Connell briefly returned to Southington, where he worked as a machinist in a bottling mill. He eventually settled in New York City where he married and worked in an auto garage. His story is quintessentially American, yet represents a slice of Catholic Americana depicting the struggles of soldiers and their families during war-time. In comparing O’Connell’s letters with those of soldiers from other wars, certain universal themes emerge, such as longing for home and excitement for new places. There are also references to music, movies, and opinions on race and gender that are very specific to place and time. War is essentially a young man’s game, but O’Connell, who turned thirty during the conflict, was relatively older. His account shows a maturity that is often absent in the surviving letters that were written by younger soldiers.

(1) Letter to Sarah O’Connell, February 8, 1919.

(2) Letter to Ellen O’Connell, ca. September 1919