If you’ve been in the campus library this semester, you may have noticed that many of the museum pieces on display were quietly christened in recent weeks.

But since a four-by-six inch exhibit label can only accommodate so much information, the following is meant to give you a glimpse of the proverbial iceberg—of which each little white rectangle is only the tip.

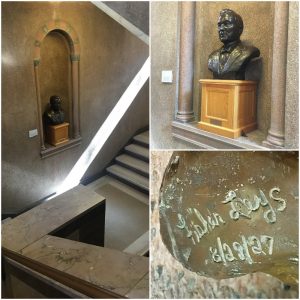

ONE: JOHN LANCASTER SPALDING

The bust of Spalding once gleamed in the niche where the smaller, darker bust of John K. Mullen has since been installed (apparently against the wishes of Spalding’s donor). Describing his intentions for the donation, Spalding’s nephew specifically requested on July 4th, 1935 that the University “place the bust in the niche in the library, there to remain.”

The prominent placement of the bust was important to the proud people of Peoria, where Spalding was appointed first bishop in 1876. Concerned that “[m]any priests have at different times and places commented on the fact that there is no memorial to him [Spalding] to be found in any of the main buildings of the University,” Spalding’s nephew—the Rev. Martin J. Spalding (1891-1960) of Chillicothe, Illinois—pulled some strings. Waiting around for the fireworks to start, he hatched the following plan in the same July 4th letter:

I have a brother, Mr. John L. Spalding, of Chicago, who for over thirty years has been connected with the Daprato Statuary Co. of Chicago, New York, Montreal, and Pietrasanta, Italy. With him I took up the matter of the cost of a life-size bust. […] Upon his death, my Most Reverend Uncle willed to Spalding Council, Knights of Columbus, in Peoria, the bust of himself and of which I know that he approved. The bust […] would be an exact copy of the one in the Knights of Columbus Hall in Peoria and made of Bianco P. Carrara marble. […] [It] would be made in Italy from a cast taken in Peoria.

Thanks to Sister Lea Stefancova (at the Archives and Museums of the Diocese of Peoria), we’ve established that the Spalding Council bust (from which CUA’s bust was copied) was executed by the Italian-born sculptor Leopold Bracony in 1900.

P.S. The Spaldings were fond of family names. The donor’s brother (with the Daprato Statuary connection) seems to have been named after John Lancaster Spalding. Meanwhile, the donor, Martin J. Spalding, was presumably named after his uncle’s uncle: Archbishop of Baltimore Martin J. Spalding (1810-1872), who in 1834 became the first American to earn a doctorate in theology.

TWO: JOHN K. MULLEN OF DENVER

The white whale of my exhibit label project, the bronze likeness of the library’s namesake—John K. Mullen of Denver (1847-1929)—has proven to be a paradoxical alloy of the obvious and the obscure.

First, a little insight into my process. As I set about drafting each exhibit label, my first stop was always our internal museum collection database. In the case of the Mullen bust, though, the data fields for the donor, maker, date of gift, and date of execution had all been left blank. My next stop was the hard file—the physical folder with paper records, shelved in the climate-controlled closed stacks of Aquinas Hall. Oftentimes, the hard file will yield details (usually in the form of newspaper clippings or correspondence) which may not have been germane to the catalog record, but which nevertheless lend perspective. Not so with Mullen. Ironically, the hard file contained only the print-out of the electronic database record (with the same four blank fields) and some photographs of the bust in its current location.

So I went back to the source. Upon closer inspection of the bust—with flashlights—my colleague and I found that the underside of Mullen’s right shoulder bears the following inscription:

Fisher Leys

8/29/27

What seemed like a breakthrough, however, petered into a dead end—or a mostly dead end. Thanks to local historian Robert Malesky, we have a new lead on the sculptor; we have reason to believe she was a woman by the name of Eleanora Fisher Leys. According to Malesky, Leys also sculpted a bronze bust of Herbert Hoover around 1928. Census records—listing her occupation as “sculptress”—indicate that Mrs. Eleanora Leys (née Fisher) was born around 1905, which means she would have only been about 22 years old when she was working on the busts of Mullen and Hoover. She died in 1995, according to the Social Security Death Index.

Although we might assume the acquisition of the bust coincided with the construction of the new library (between 1925 and 1928)—especially since the date inscribed on the bust falls within that time frame—I haven’t found any records to support that assumption. Yet.

THREE: DANTE

With the Dante bust, we have the exact inverse of the predicament with the John K. Mullen bust; in this case, the donor and the date of the gift are well-documented, but clues as to the maker and the date of execution are mired in a series of coincidences.

The distinctive two-tone bust of Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) was presented to CUA on April 14, 1931 by the Italian club then on campus, Il Circolo Italiano.

According to the April 2, 1930 issue of CUA’s student newspaper, The Tower, the same Italian club gave away a bust of Dante the year before; that bust was presented to Director of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra Maestro Arturo Toscanini (1867-1957) on March 25, 1930, during Georgetown University’s Founders Day celebration. The Tower article continues:

Following the reception, the members of the Il Circolo, through their Secretary, Mr. John Del Vecchio, presented to Signor Toscanini a beautiful Italian marble bust of Dante, executed by the prominent Florentine sculptor, Carlo Romanelli.

This coincidence has led some at CUA to speculate that our bust of Dante was also sculpted by Carlo Romanelli. Some online sources indicate that Carlo Alfred Romanelli (1872-1947) was the son of Italian sculptor Raffaello Romanelli (1856-1928); he studied with his father and with Augusto Rivalta at the Royal Academy of Art. According to the Smithsonian Institution Research Information System (SIRIS), Raffaello Romanelli sculpted the bust of Dante on Belle Isle in Detroit, Michigan.

Today, Il Circolo Italiano survives through its “daughter organization,” The Italian Cultural Society of Washington, D.C. (ICS). In an April 2007 issue of the ICS’s paper, Poche Parole, then-president Mr. Luigi De Luca mentions the “gift of a beautiful bust of Dante Alighieri.” He says, “Thanks to that gift, Dante keeps me company during my studies of Ancient Greek on the third floor of the John Mullen of Denver Library.”