The word ‘incunable’ comes from the Latin incunabula, which means ‘swaddling clothes’ or ‘cradle’. In the context of books, the term refers to the printed word in its infancy, which began with Gutenberg’s invention of movable type some time around 1450 and was first manifested in 1455 by Gutenberg’s 42-line Bible. Starting in Mainz, printing presses with movable type quickly spread from Germany to all of Europe throughout the 15th century: Spain in 1474, England in 1476 and Portugal in 1487. Strictly speaking, the period of incunables ends in Europe in 1501, a date by which many of the trappings of a printed book as we know it today – title page, numbered pages, illustrations and, importantly for catalogers, publication information – had been firmly established in European printing.

However, beyond this restricted sense the word incunable is often adjectivized to describe early printing in a specific geographic or cultural area. In Margaret Bingham Stillwell’s opinion, it is eminently proper to speak of incunabula in the context of the Americas because both Gutenberg and Columbus “altered the course of history more effectively than anyone since the birth of Christ.” (p. x) This seems especially apt when we consider that history itself is nothing more than the documentary record of human memory and furthermore, that during the Age of Exploration the printed word was essential to publicizing the so-called discoveries of the various European powers in the New World, both enabling them to stake their claims and igniting the imaginations of rival European monarchs with the possibility for commerce and evangelism and goading them into the fray of imperial conquest.

We may thus initiate the period of American incunables with Columbus’ arrival in the Americas and the subsequent publication in 1493 his Epistola Cristofori Colom… In 1500 the first Europeans, led by Pedro Álvares Cabral, set foot on the land that would come to be called Brazil. The first printed account of Cabral’s voyage is to be found in Fracanzano da Montalboddo’s Paesi Nouamente Retrouati…. in Venice in 1507. It is the oldest printed book in the Oliveira Lima Library’s holdings.

As Stillwell notes, throughout the 16th century the majority of works on the Americas were still being printed in Europe, but by 1700 “the art of bookmaking…had become an established and influential factor in colonial life” in both North and South America. For many bibliographers, the various independence movements in the colonies during the late 18th and early 19th centuries mark the end of early printing in the Americas.

So when did printing begin in Brazil? How long did its period of early printing last? The answer to this question, like that of so many others, is deceptively complex and provides one of a host of examples of Brazil’s truly unique and cosmopolitan development.

The history of printing in Brazil offers a peculiar example within the context of the other European colonies in the New World, for whereas printing presses appeared within decades of the establishment of colonies in Spanish and English America, none would be officially recognized in Brazil until the arrival of the Portuguese court to Rio de Janeiro in 1808, a full 300 years after the arrival of Europeans in Brazil.

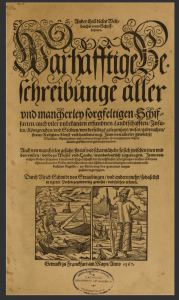

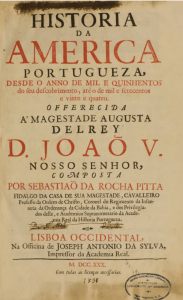

That is not to say that this Portuguese colony did not pique the interest of learned Europeans throughout its first three centuries of existence, nor that the inhabitants of Brazil did not publish works during the colonial period. The Oliveira Lima Library’s holdings provide a wealth of material as evidence to the contrary, such as Hans Staden’s Warhafftige Beschreibunge aller und mancherley sorgfeltigen Schiffarten… published in Frankfurt am Main in 1567 and Sebastião da Rocha Pitta’s Historia da America Portugueza, desde o anno de mil e quinhentos de seu descobrimento, até o de mil e setecentos e vinte e quatro, the first history of Portuguese America written by a Brazilian, published in Lisbon in 1730. Yet the fact nevertheless remains that it took 300 years for printing to be officially established in Brazil. Why is that?

At the risk of nuance, the lack of publishing houses in colonial Brazil can be attributed to two major factors. The first was the Portuguese crown, which jealously guarded the benefits of the mercantilist system which maintained Lisbon as the center of political, economic and cultural power of Portugal’s immense and far flung empire. Though this apprehension on the part of the Portuguese metropole was shared by Spain, Portugal’s policies seemed particularly restrictive of the production or entry of books into its colony. The second force at play was that of the Holy Office of the Inquisition, whose censorial power focused on ensuring that no publication run afoul of the Inquisition’s moral strictures.

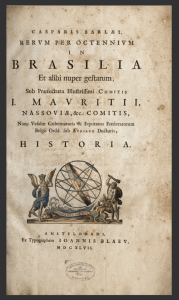

Despite these eminently unfavorable conditions, three attempts were made at establishing printing houses in Brazil prior to 1808. The first was initiated by the Dutch during their brief reign over northeastern Brazil in the 17th century. It was fruitless, for Pieter Janzsoon, the printer hired for the task, died weeks after his arrival in Brazil in 1643. While unsuccessful in producing any books inside of Brazil, Dutch rule did produce many accounts of Brazil published in Europe, including Caspar van Baerle’s wonderfully illustrated Rerum per octennium in Brasilia… printed in Amsterdam in 1647.

A second attempt at establishing a press was made in Recife, Pernambuco, though the only evidence of its existence lies in two royal orders, the first from 1706 and the second from 1747, to seize the press’s materials.

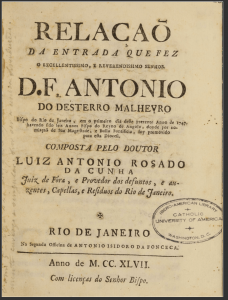

The last and only successful attempt at printing in Brazil before 1808 was undertaken by Antonio Isidoro da Fonseca, who, for reasons as of yet uncertain, departed Lisbon in 1746 to found a publishing house in Rio de Janeiro. This daring endeavor would last a mere two years, from 1747-1749, producing a few pamphlets and the first book ever printed in Brazil, Relaçaõ da entrada que fez o excellentissimno, e reverendissimo senhor D. Fr. Antonio do Desterro Malheyro Bispo do Rio de Janeiro. According to Jerônimo Estrada de Barros (2012), the Oliveira Lima Library’s is one of less than ten known copies in the world.

The arrival of the Portuguese court to Rio de Janeiro in 1808 led to the founding that very same year of Brazil’s first officially sanctioned publishing house and resulted in an explosion of books in the colony. Indeed, between 1808 and 1822, the Impressão Régia (Royal Publishing House) “would print nearly 1,500 books and over 700 laws, decrees, alvarás, royal letters, etc” an output which exceeded that of its counterpart in Lisbon. (Gauz, p. 43) Among the Oliveira Lima Library’s many books and pamphlets printed by the Impressão Régia during the waning years of the colonial period is Reflexões sobre alguns dos meios propostos por mais conducentes para melhorar o clima da cidade do Rio de Janeiro, the first book printed by the Impressão Régia in 1808.

By 1822, Brazil had all but achieved independence. No longer beholden to the colonial metropole or the censorship of the Inquisition, publishing would greatly expand, marking the end of the period of early printing in Brazil and the beginning of a period of growth in the book industry in which academics and bibliophiles such as Manoel de Oliveira Lima surely must have reveled.

Bibliography

Great article Henry!