Equipe do Projeto Memória Acadêmica da Faculdade de Direito do Recife

Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife – Brasil

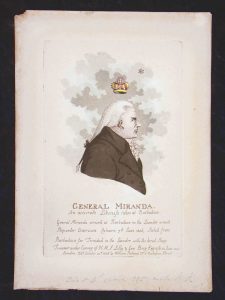

Em 2019, o Projeto Memória Acadêmica da Faculdade de Direito do Recife, atividade extensionista interdisciplinar desenvolvida na Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (UFPE), firmou importante parceria com The Oliveira Lima Library (OLL) da Catholic University of America. A biblioteca amigavelmente cedeu cerca de 40 exemplares de livros, folhetos, teses e discursos de egressos da Faculdade de Direito do Recife (FDR) para disponibilização digitalizada no site do Projeto Memória Acadêmica. A ação assume contornos de grande relevância para as duas instituições universitárias, uma vez que reforça a conexão de Manoel de Oliveira Lima, intelectual que dá nome à OLL, com o Recife, cidade onde nasceu em 1867.

Manoel de Oliveira Lima e a Faculdade de Direito do Recife

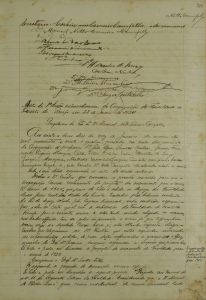

A notoriedade de Manoel de Oliveira Lima como professor, historiador e diplomata não passou despercebida entre aqueles que atuavam na Faculdade de Direito do Recife, instituição historicamente responsável por formar grande parte das mentes intelectuais brasileiras do século XIX e início do século XX. Nesse sentido, em 30 de novembro de 1923, em sessão realizada na Congregação da Faculdade de Direito do Recife, é lançada a proposta de concessão do título de professor honorário da FDR ao Dr. Oliveira Lima. O pedido é apreciado e aprovado por unanimidade pelos professores durante a 1ª sessão extraordinária da Congregação da FDR em 22 de janeiro de 1924.

Em consulta à ata referente a esta última sessão, disponível digitalmente no Arquivo da Faculdade de Direito do Recife, nota-se que, como justificativa para o título, considerou-se não apenas a atuação de Oliveira Lima em diversas instituições de ensino estadunidenses, mas também a relação do intelectual com a Faculdade de Direito do Recife, local em que realizou, a convite dos estudantes, diversas conferências de destaque. Nesse mesmo documento, menciona-se, ainda, a indicação de Oliveira Lima para reger a cadeira de Direito Internacional da Universidade Católica de Washington.

O Projeto Memória Acadêmica e a Oliveira Lima Library

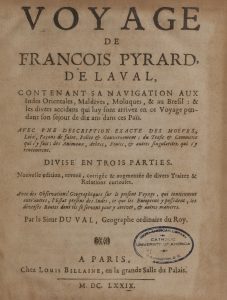

A parceria firmada entre o Projeto Memória Acadêmica da Faculdade de Direito do Recife e a Oliveira Lima Library retoma as relações institucionais concretizadas na memória de Manoel de Oliveira Lima. Recordamos, aqui, que as obras em posse da OLL resultam da doação que o diplomata concedeu à Catholic University of America na década de 1920, tornando-se ele mesmo seu primeiro bibliotecário. Entre os títulos doados, encontram-se obras importantes para a história da FDR, fato que justifica o interesse do Projeto Memória Acadêmica pelo acervo da OLL.

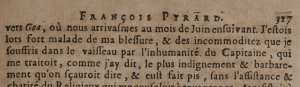

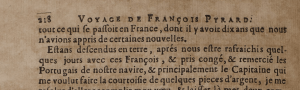

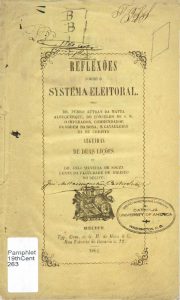

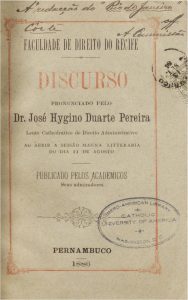

Tendo em vista a atuação do Projeto Memória Acadêmica na difusão de documentos que contribuem para a preservação da memória da FDR, muitas dessas obras cedidas pela OLL já estão disponíveis para consulta no sítio eletrônico do projeto. Obras como Reflexões sobre o systema eleitoral seguidas de duas lições sobre as vantagens da eleição directa, de Pedro Autran da Matta Albuquerque (1862) e discursos pronunciados na Faculdade de Direito do Recife como o do Dr. José Hygino Duarte Pereira (1886) estão entre os documentos que atualmente podem ser acessados pelo público.

Não bastasse a contribuição que o acervo da OLL fez ao projeto, enriquecendo o material bibliográfico disponibilizado ao público, o ato mereceu reconhecimento na Assembleia Legislativa de Pernambuco, que pelo Ofício Sec. nº 20926/2019, de autoria do deputado William Brigido, concedeu um Voto de Aplausos ao Projeto em razão da importante parceria estabelecida do Projeto Memória Acadêmica com a Oliveira Lima Library.

Idos quase cem anos do Título Honorário e da visita à FDR, pode-se dizer que Oliveira Lima se fez novamente presente no Recife, sua cidade natal, através da colaboração entre as duas instituições.

Sobre o Projeto Memória Acadêmica

O Projeto Memória Acadêmica da Faculdade de Direito do Recife, como atividade de extensão interdisciplinar desenvolvida no âmbito do Centro de Ciências Jurídicas (CCJ) da UFPE, tem como objetivo contribuir com a política de preservação do patrimônio cultural da Faculdade de Direito do Recife por meio da realização de uma série de ações, congregando a comunidade acadêmica da UFPE e a sociedade em geral.

O projeto teve início em 2016, sob a coordenação do Prof. Dr. Humberto Carneiro, do Departamento de Teoria Geral do Direito e Direito Privado/UFPE. Atualmente, a vice-coordenadoria é exercida por Ingrid Rique, servidora do Arquivo da FDR. O projeto conta, também, com a participação de estudantes dos cursos graduação em Direito, História e Museologia, bem como de membros externos à UFPE e servidores lotados no CCJ.

Para além da digitalização e disponibilização de Obras, Memórias e Documentos Históricos da Faculdade de Direito do Recife, o Projeto Memória Acadêmica realiza atividades que visam à integração da instituição com a sociedade, tais como exposições de documentos históricos, visitas guiadas ao prédio histórico da FDR, minicursos e produção e publicação de pesquisas acadêmicas. Durante a pandemia, em razão da suspensão das atividades presenciais, o projeto passou a realizar eventos online, o que possibilitou a participação de pesquisadores de outras cidades do país em nossas atividades.

Informações de contato:

- Email: memoriafdr@gmail.com

- Site: https://www.ufpe.br/memoriafdr

- Instagram: @memoriafdr

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/memoriafdr/

Referência:

Atas da Congregação da Faculdade de Direito do Recife 1923-1927. Disponível em: https://www.ufpe.br/documents/590249/2995131/Atas+da+Congrega%C3%A7%C3%A3o+FDR+1923-1927.pdf/76327750-cb2e-4781-b8c8-e8a69bbe6fed. Acesso em: 21 jun. 2021.