Dr. Jan Levin Propach

Postdoctoral Researcher at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich – Department of Catholic Theology

The Oliveira Lima Library contains a collection of engraved illustrations showing Jesuit martyrdoms during the persecution of Christianity in 17th century Japan. Even though these illustrations were made in Europe in a propagandistic manner, they tell a story which is not well-known in the West: the rise and fall of Christianity in Early Modern Japan.

In 1549 Francis Xavier S.J. (1506–1552)—one of the first disciples of Ignatius of Loyola S.J. (1491–1556)—arrived at Japan’s southern Island Kyushu together with two other Jesuits and a former Samurai. What political context did the missionaries enter? Since the Ōnin War (1467–1477), Japan was no longer reigned by the emperor and a shogun (Muromachi Shogunate). Instead, dozens of small local rulers (daimyō and kunishū), different Buddhist monasteries fought for their supremacy. The three Great Unifiers Oda Nobunaga (1534–1582), Toyotomi Hideyashi (1537–1598) and Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616) attempted to bring the Age of Warring States (sengoku) to an end and to unify the country under the reign of a shogun again.

The destiny of Christianity in Japan is neatly wedded into this Age of Warring States. Many Japanese local lords allowed the Jesuits to proselytize their subjects, because they benefited from the Portuguese trade and weapon technologies. They also perceived in Christianity an instrument against the influence of different powerful Buddhist sects. On the other hand, Christian missionaries were seen as representatives of foreign powers trying to increase their influence in Japan.

Despite this, the early Japanese missions were highly successful: about 150.000 Japanese were converted in 1583; 75 Jesuits organized the Japanese mission; there was a novitiate in Usuki, seminaries in Arima and Azuchi and about ten Jesuit residences throughout Japan. However, missionaries would be increasingly perceived as antagonists to the efforts to reach the country’s unity, especially after the donation of Nagasaki to the Jesuits in 1580. Thus on July 24th, 1587 Hideyoshi issued an edict that expelled the Jesuit missionaries. This first edict had only a limited impact on the Japanese mission, although it caused the confiscation and demolition of Christian buildings, such as the college in Funai and the novitiate in Usuki. From this moment on, the Jesuit mission focused on Kyushu.

The pragmatic politician Hideyoshi only reluctantly tolerated the Jesuits’ bidding out of an interest in and dependence on trade with the Portuguese. These economic relations could only be achieved with the help of the Jesuits. Tokugawa Ieyasu, who followed Hideyoshi after his death in 1598, tolerated the Jesuits’ missionary activities for economic reasons too, but once he issued a trade permit for the Dutch (1609) and the English (1613), he limited the Portuguese ships to the port of Nagasaki. There was no further need of tolerance for Christianity to get involved in the profitable European trade. And when in 1612 a court intrigue—involving Okamoto Paulo Daihachi and Arima Harunobi who were both Christians—was disclosed, Ieyasu’s aversion against the Christian missionaries increased considerably.

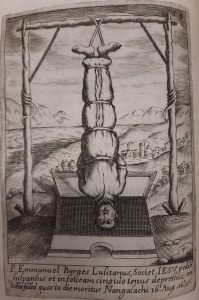

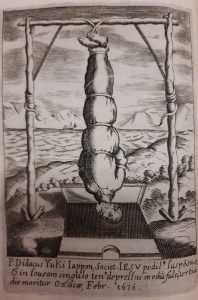

In 1614, the bakufu, or military government, announced the expulsion of all missionaries from Japan. This edict was renewed under Ieyasu’s successor Tokugawa Hidetada (1579-1632) in 1616. The great martyrdoms in Kyoto 1619 (88 martyrdoms), Nagasaki in 1622 (55 martyrdoms) and Edo, now Tokyo, in 1624 (50 martyrdoms) all attest to the serious commitment of the shogun’s government to this new policy. Between 1614 and 1650, 2,128 Christians died under the persecution, 71 of whom were European missionaries (1). The following illustrations from Antonio Francisco Cardim’s Elogios e ramalhete de flores… (1650) in the Oliveira Lima Library depict the martyrdoms of Emmanuel Borges S.J., Augustinus Ota S.J. (1572–1622) and Diego Yuki S.J. (1574–1636) by anatsurushi (2) and by smiting with a sword.

By 1643, after all of Japan’s missionaries were forced either to flee to China and the Philippines, were killed or apostatized, about one hundred missionaries had secretly entered Japan to maintain the religious, and especially the sacramental life of the Church. Between 1714, the year of the death in Edo of Giovanni Battista Sidotti (1668–1714), the last priest to enter Japan secretly, until the enactment of religious freedom in 1889, Christianity survived in the underground, disconnected from the Church hierarchy. Many of those Hidden Christians rejoined the Catholic Church in the late 19th century. However, down to the present day some Christian communities remain hidden in the underground, opting not to reenter the Catholic Church in order to keep their own religious identities in contact with the greater Japanese religious environment. (3)

(1) For a list of all Japanese martyrdoms see Boxer, Charles Ralph. The Christian Century in Japan (1549–1650). Berkeley: University of California Press, 1951, 448.

(2) Anatsurushi was a method of torture by facing the victim upside down in an Excrement-filled hole in the ground; a lid closed on the neck. Slow death made it possible for those who were tortured to renounce their faith and thus save their lives.

(3) Cf. Turnbull, Stephen. The Kakure Kirishitan of Japan. A Study of Their Development, Beliefs and Rituals to the Present Day. Richmond: Japan Library Press, 1998; Harrington, Ann M. Japan’s Hidden Christians. Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1993 and Pella, Kristian. The Kakure Kirishitan of Ikitsuki Island. The End of a Tradition. Uppsala: Uppsala University, 2013.