Heather Roller

Associate Professor of History

Colgate University

It was the dry season of 1845, and the Guaikurú were on the move again. Some groups rode on horseback across the grasslands, while others navigated in canoes along the Paraguay River or its tributaries. These Native peoples had been visiting Brazilian and Paraguayan forts and garrison towns for more than a half century, following a series of fragile peace agreements negotiated between Guaikurú leaders and Spanish or Portuguese representatives. Much had changed over those decades, but the Guaikurú remained powerful actors in this borderlands region. One outsider who described them in these terms was the French naturalist Francis de Castelnau, who led a scientific expedition to the interior of South America.

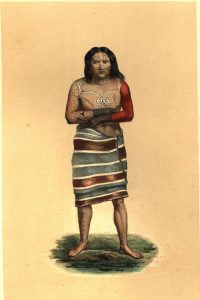

Two remarkable illustrations of the Guaikurú appear in a volume of Castelnau expedition “views and scenes,” which can be found at the Oliveira Lima Library. The first is a portrait of a warrior whose path crossed with that of the French naturalist at the garrison of Albuquerque in 1845 (figure 1). Castelnau gathered that this group of Guaikurús had arrived from the Chaco region only a few days before: “They told us that they had massacred the population of a Spanish town [in Paraguay] and that, being pursued, they came to place themselves under the protection of the Brazilian garrison.” A subgroup, which Castelnau characterized as a “much more savage” band of Kadiwéus, had similarly just crossed into Brazil from Paraguay, to escape retribution from an Indigenous enemy.[i] Both groups were eager to trade some horses for liquor and other supplies. Castelnau was fascinated by the appearance of the Kadiwéu visitors, who—like the man in the portrait—“paint the body with genipapo [ink], covering it with precise figures made of concentric lines and beautiful arabesques…They also frequently paint their hands black, giving the impression of wearing gloves.”[ii]

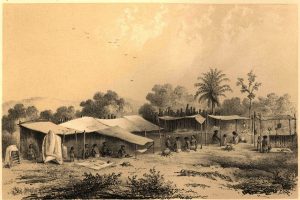

The second illustration depicts an encampment near Albuquerque that Castelnau described as inhabited by another subgroup of Guaikurús, featuring open-walled shelters arranged in a semicircle (figure 2). Although this subgroup was described in his account and in official reports from the 1840s as “aldeado”—or settled in a state-run village—other evidence makes clear that they remained mobile and autonomous. Indigenous raiding in the borderlands remained common in this period, and the lands between forts in Brazil and Paraguay still effectively belonged to the Guaikurú and Kadiwéu. After the Frenchman visited the Paraguayan fort at Olimpo, he was escorted back to Coimbra Fort on the Brazilian side by a group of soldiers who were terrified to venture into the open terrain. On high alert for Native raiders, “every grass mound of the Chaco seemed to them a Guaikurú ready to attack.” The Paraguayan soldiers’ fears, as it turns out, were justified: upon Castelnau’s return to Brazil, he was told that the Guaikurús had been tracking the party and would have attacked it, had it not been for the presence of the French travelers. He also discovered that the Guaikurús had already given the Brazilian commander at Coimbra a precise account of the trip to Olimpo, fulfilling their longstanding roles as borderland spies and informants.[iii]

I included both of these illustrations in my recent book, Contact Strategies: Histories of Native Autonomy in Brazil. The central argument, as suggested by the book’s title, is that Indigenous groups took the initiative in their contacts with Brazilian society. Rather than fleeing from that society, they actively sought to appropriate what was useful and powerful from the world of the whites. (In this context, “white” was broadly defined as non-Indigenous.) At the same time, many Indigenous people chose not to live like whites. Groups like the Guaikurú refused permanent settlement, rejected most missionary overtures, and continued to move and gain their subsistence in the old ways—even as they acquired new, useful things like axes, guns, and horses. They also aimed to control the pace and extent of contact: they might open up to outsiders for a period of time and then decide to limit interactions for as long as was collectively deemed necessary. At the time of Castelnau’s expedition, the Guaikurú were using strategies of alliance and warfare in an effort to maintain their autonomy and to reassert authority over people and territory.

[i] Francis de Castelnau, Expedição às regiões centrais da América do Sul (Rio de Janeiro: Itatiaia, 2000), 365, 366.

[ii] Castelnau, Expedição, 366-367.

[iii] Castelnau, Expedição, 386 (quotation), 388.